Demographics

Region: Mid West

LGA: Cue

Industry: Mining

Other Names: Paton’s Find, Coolardy Reef, Coolardy Reward, Little Bell, Townsend, Paton’s Coolardy Reward, Coodardy, Dutton’s Soak

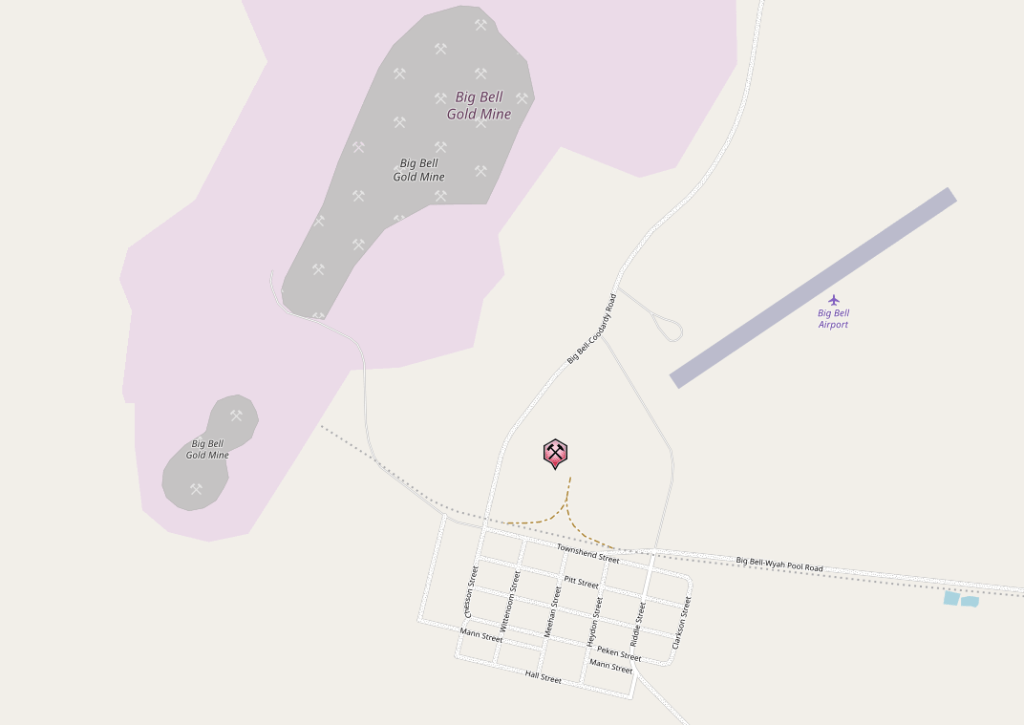

Coordinates: -27.135745379819852, 117.66476592663122

What3Words: ///forecaster.bedroom.tinny

Gold discovered: 1891

Gazetted: 1936

Abandoned: 1955

Abstract

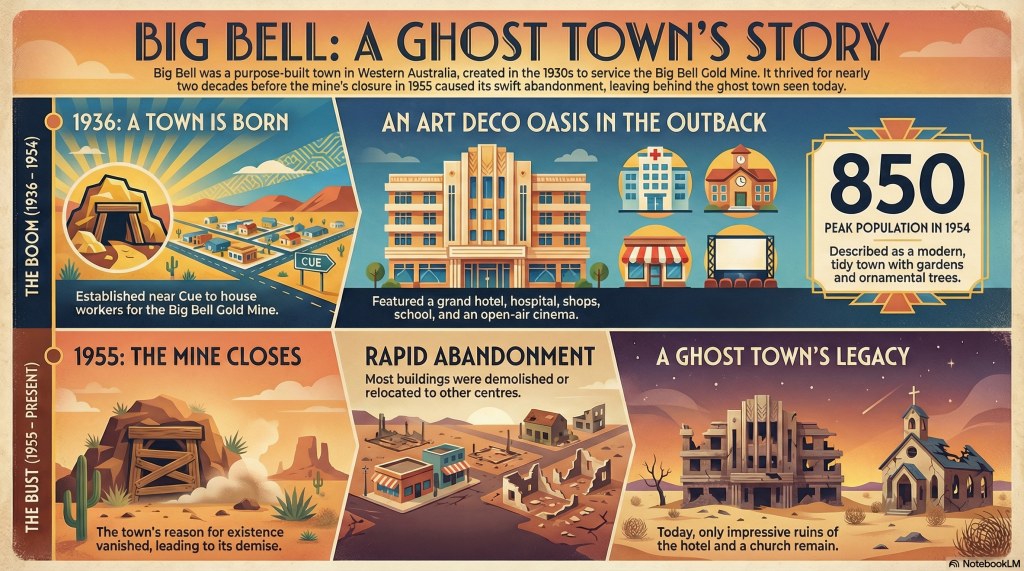

The history of Big Bell, Western Australia, serves as a poignant microcosm of the transitory nature of mining settlements in the arid outback. Emerging from a gold discovery that predates the regional hub of Cue, the town witnessed two distinct lives: a fragmented early period of prospecting followed by a spectacular, state-sanctioned boom in the mid-1930s. Driven by the economic weight of the Premier Gold Mining Company and the logistical lifeline of a dedicated railway, Big Bell transformed from virgin bush into a modern township of nearly 1,000 residents, boasting Art Deco architecture and Australia’s longest bar. However, the town’s existence was inextricably linked to the profitability of its low-grade ore. When the mine ceased operations in 1955, the social and economic fabric dissolved almost overnight, leaving behind only skeletal ruins that today stand as silent monuments to a vanished era of goldfields prosperity.

History

To the modern traveller driving 30 kilometres southwest of Cue, the ruins of Big Bell appear like a mirage shimmering against the red dirt of the Murchison. While today it is a quiet expanse of crumbling brick and dirt tracks, for twenty years between 1936 and 1955, it was one of the most modern and vibrant towns in Western Australia. Its story is a classic tale of economic ambition, social resilience, and the eventual triumph of a harsh environment over human settlement.

Early Finds and the “Little Bell”

The history of the site stretches back further than many realize, with activity at what was then called Coolardy Reef or Paton’s Find dating to 1891—predating the establishment of Cue by roughly a year. The first official registration of a claim occurred in 1904, when Harry Paton and W. Smith filed for “Paton’s Coolardy Reward”.

In these early years, the area was a patchwork of smaller leases. Notable among them was a mine operated by the U.K.-based Blue Bell Proprietary, which locals nicknamed “Little Bell”. It is widely believed that the name Big Bell was adopted simply to differentiate the larger neighbouring deposit from its smaller counterpart. Between 1912 and 1926, miners like James Chesson and Bill Heydon extracted 78,000 tons of ore using open-cut methods before the site fell into a period of dormancy during the Great Depression.2 3 4

The 1936 “Birth” of a Modern Town

The true transformation of Big Bell began in 1935 when the Premier Gold Mining Company announced plans to develop the massive low-grade ore body. This was not merely a mining venture; it was a state-backed exercise in town-building. The Western Australian government entered a historic agreement in 1936 to construct a railway from Cue to facilitate the mine’s development.5 6 7

The townsite was gazetted in 1936, but not without some local debate over its identity. The Cue Road Board initially recommended the name “Townsend” to honour the original settlers of Coodardy Station , with the main thoroughfare to be named Coodardy Street. Ultimately, the fame of the mine won out, and the name Big Bell was retained. Streets were laid out with surgical precision, named after mine managers like Pitt and Paton, and prominent local pastoralists such as Wittenoom and Lefroy. By June 1936, over 100 land blocks had been sold to eager residents and speculators.8 9

Infrastructure and Environmental Adaptation

Life in the Murchison was, and remains. environmentally challenging. Big Bell sat upon an arid plateau where trees were a rare sight. However, the town possessed a secret weapon: it was surveyed on deep sandy loam, and excellent water was discovered at reasonable depths.

In March 1936. the Western Australian government made an agreement to build a railway to Big Bell with the American Smelting and Refining Company . The railway construction was authorised by the Cue-Big Bell Railway Act 1936 in November 1936. Carpenters were busy building staff quarters, and miners were erecting temporary poppet legs over the main shaft site. The first train arrived in Big Bell on 6 January 1937, and the line officially opened on 12 August 1937.10 11

Mining operations re-started in 1937, with production treating 40,000 tons of ore per month. The town quickly developed from virgin bush into a settlement with surveyed streets, roads, and dozens of residences.12

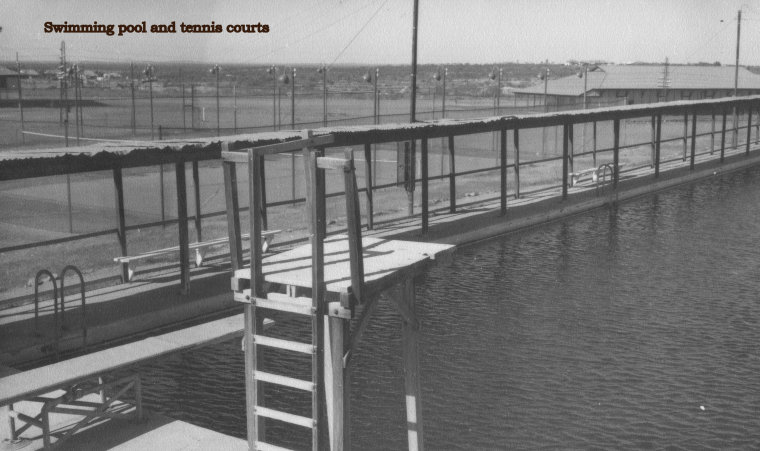

By 1937, a government-operated bore and storage tank reticulated water throughout the town. This allowed residents to painstakingly tend to ornamental trees and small patches of green lawn, creating a lush oasis in the desert that surprised visitors. A modern power-house provided 24-hour electricity, fueling not just the mine but a thriving business district that included general stores, a newsagency, a barber shop, and even a milk bar.13 14

The social crown jewel of the town was the Big Bell Hotel, opened in 1937. Constructed of 300,000 bricks made in a nearby kiln, the grand two-storey building was a masterpiece of Art Deco style, featuring curved balustrades and brick colonnading. Local legend, and historical record, claims it housed the longest bar in Australia at the time, a necessary refuge for thirsty miners emerging from the dust of the shafts.15 16

Social Life and Community Struggles

At its peak in the early 1950s, the population reached between 850 and 1,000 people. It was a diverse community, including many Italian migrants like Rocco Tassoni and Giovanni Pantarelli, who sought new lives in the goldfields. Social life was “highly developed,” centering on sporting clubs, church groups, and the cinema (or “picture house”), which was famously destroyed by fire in 1938 only to be rebuilt later.17 18

SLWA19

The town’s health was overseen by the Big Bell Hospital, which opened in 1941 after years of local fundraising through boxing matches and balls. The medical history of the town was often as dramatic as the mining. Dr Leslie Ronald Jury, the hospital’s medical officer in 1941, was a particularly “colourful” figure; a card-carrying Communist who was later embroiled in a scandalous divorce after falling in love with the hospital matron, Sheila Wheatley.20

SLWA21

Despite the modern facilities, the economic reality of mining was often brutal. Coronial inquiries into mining fatalities, such as the deaths of Harold Connor and Lubermann Muson, frequently ended with the verdict of “accidental death” and the sobering note that “no blame was attachable to anyone,” with the word “compensation” rarely mentioned in the records of the era.22

Decline and the Silence of the Dust

The decline of Big Bell was as rapid as its rise. The Second World War caused a temporary closure between 1943 and 1945 as men were recruited and machinery was diverted to the war industry, leaving only 15 residents in the town during those dark years.23 24

The mine reopened after the war, but by the mid-1950s, the low-grade ore was no longer profitable to extract. The announcement of the mine’s closure in 1955 was the town’s death knell. Because the town existed solely to service the mine, it had no other economic reason to be.25 26

The exodus was swift. The railway line closed on 31 December 1955. Families departed for Cue or Mt Magnet, often dismantling their houses and taking the timber and iron with them. By 1959, the Woman’s Weekly reported a haunting scene: billiard tables still stood in the miners’ club and an 18-hole golf course lay abandoned, while a lone resident, Eddie Hannan, maintained a flourishing vegetable garden amidst the encroaching desert.27 28

Modern Legacy

There was a brief return of industry in the 1980s when modern technology made the deposits viable again, but the workers lived elsewhere; the town of Big Bell remained a ghost. Mining ceased again in 2003, and the plant was dismantled in 2007.

Today, the Big Bell Hotel ruins and the concrete walls of the Catholic Church are the most substantial remains of a dream that lasted only two decades. The original street layout is still visible from the air as dirt tracks, a skeletal fingerprint of a town that once boasted the “longest bar” and green lawns in a land of red dust. Big Bell stands as a stark reminder of the precariousness of human settlement when it is built on the shifting fortunes of gold.29

An hotel reared its lofty head

Beside a lilac.

No patrons now it could be said,

Not since way back.

The walls are dusty brown,

Once were white.

Inside curtains billow round,

Once were bright.

Pretty wallpaper covered in dirt

Peeling everywhere.

Drunken beds but no forms inert

Resting there.

Church with steeple rising high,

Pews in neat rows.

Long since pastor raised his cry

Of religious prose.

Bell no longer on its stand,

It tolls nearby

To call the boss and hired hands

Coodardy Station nigh.

House stumps standing neatly

Along the street.

Give mute testimony

Of houses once neat.

Pool is dry,

hospital empty,

Creeper bloom.

Mine paraphernalia and shanty

Like the tomb.

Once a thriving community

But gold gone.

Now a dusty, dirty entity

A decade on.30

Timeline

- 1891: First activity at “Cooldardy Reef” (Paton’s Find), predating Cue.

- 1902–1904: Gold discovery by Harry Paton; registration of “Paton’s Coolardy Reward”.

- 1912–1926: Early mining operations by James Chesson and Bill Heydon.

- 1935: Premier Gold Mining Company announces plans to develop the Big Bell Mine.

- 1936:

- March: Agreement reached between the WA government and American Smelting and Refining Co. to build the railway.

- August: Big Bell townsite is officially gazetted.

- November: The Cue-Big Bell Railway Act 1936 is authorised.

- 1937:

- January: The first train arrives in Big Bell.

- August: The railway officially opens and the local school commences classes.

- September: The Big Bell Hotel opens for business.

- 1938: The town cinema is destroyed by fire in April.

- 1941:

- January: Big Bell Hospital officially opens to patients.

- May: Official ceremonial opening of the hospital by W. Marshall, M.L.A..

- 1943–1945: Mine and hospital close temporarily due to the impacts of World War II.

- 1946: Big Bell Hospital and mine reopen.

- 1951: Town population reaches its peak, estimated at over 1,000 residents.

- 1954: Final peak of 850 residents recorded in guidebooks; described as a town of ornamental trees and gardens.

- 1955:

- January: Mine closure announced; salvage operations begin.

- December: The Big Bell branch railway line closes permanently.

- 1960: Formal act of Parliament officially discontinues the Big Bell railway.

- 1980: Mining operations resume under joint ownership (ACM Ltd and Placer Pacific).

- 2003: Modern mining operations cease permanently.

- 2007: The mining plant is dismantled and moved to Westonia.

Map

Sources

- Crack, P.H., 2009. The ruins of the Big Bell Hotel. Image retrieved from Wikipedia on 15 Oct 2024 at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:BigBellHotel2009.jpg ↩︎

- mindat.org, n.d. Big Bell Gold Mine (Paton’s Find, Murchison Bell), Cue, Cue Shire, Western Australia, Australia. Retrieved 28 Dec 2025 from https://www.mindat.org/loc-246053.html ↩︎

- Moya Sharp, n.d. Outlook Family Histy: Big Bell – Kyarra District. Retrieved 28 Dec 2025 from https://outbackfamilyhistory.com.au/records/record.php?record_id=779&town=Big+Bell ↩︎

- Western Australia Now and Then, n.d. Big Bell. Retrieved 25 Nov 2025 from https://www.wanowandthen.com/Big-Bell.html ↩︎

- Wikipedia, 2024. Big Bell, Western Australia. Retrieved 28 Dec 2025 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Bell,_Western_Australia ↩︎

- WA Now and Then: refers to Premier GM Company ↩︎

- Wikiwand, n.d. Big Bell, Western Australia. Retrieved 28 Dec 2025 from https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Big_Bell,_Western_Australia ↩︎

- Big Bell Mine (1936, April 3). Coolgardie Miner (WA : 1935 – 1954), p. 2. Retrieved December 28, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article218002621 ↩︎

- Heritage Council of WA, 2016. Inherit: Big Bell Townsite. Retrieved 28 Dec 2025 from https://inherit.dplh.wa.gov.au/public/inventory/printsinglerecord/d38c2341-15fc-46f2-8c92-10433cfa9bfa ↩︎

- Wikipedia: refers to Government railway ↩︎

- Coolgardie Miner, 1936: refers to early infrastructure development ↩︎

- Inherit: refers to mining operations ↩︎

- WA Now and Then, n.d. Big Bell Ghost Town – Western Australia. YouTube video retrieved 28 Dec 2025 from https://youtu.be/IotIWBBRMjI?list=TLGGEgmhKGZeORgyODEyMjAyNQ ↩︎

- Bojan Ivanov, 2017. Abandoned Spaces: Big Bell, Western Australia – this once bustling town is slowly turning into dust. Retrieved 28 Dec 2025 from https://www.abandonedspaces.com/towns/big-bell-western-australia.html ↩︎

- Kiddle, 2025. Big Bell, Western Australia facts for kids. Retrieved 28 Dec 2025 from https://kids.kiddle.co/Big_Bell,_Western_Australia ↩︎

- Wikipedia: refers to construction and structure of hotel ↩︎

- Inherit: refers to population and services ↩︎

- Peter Stride,2022. Big Bell Hospital, 1941-1955 – Paper. Ann Clin Med Case Rep. Pub 2022; V10(3): 1-23. Retrieved 28 Dec 2025 from https://acmcasereport.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ACMCR-v10-1857.pdf ↩︎

- State Library of WA, n.d. Big Bell: historic photos of Big Bell and its people. Retrieved 28 Dec 2025 from https://encore.slwa.wa.gov.au/iii/encore/record/C__Rb3079487 ↩︎

- Stride, 2022: refers to multiple examples of inquests and trials ↩︎

- SLWA: Big Bell Hospital BA2227/128 ↩︎

- Stride, 2022: refers to mining deaths ↩︎

- Inherit: refers to war years activity ↩︎

- Ivanov: refers to war years activity ↩︎

- WA Now & Then: refers to post war activity and decline ↩︎

- mindat.org: refers to post war acivity and decline ↩︎

- Wikipedia: refers to closure ↩︎

- WA Now & Then / YouTube: refers to closure ↩︎

- Inherit: refers to more recent times at Big Bell ↩︎

- Stride, 2022 : Ghost Town of Big Bell by Colleen O’Grady. ↩︎

- mindat: OpenStreetMap showing relative location of mine and townsite retrieved 25 Dec 2025 ↩︎