The Town That Had It All

State Library of Western Australia 1

Demographics

Region: Goldfields-Esperance

LGA: Kalgoorlie Boulder

Industry: Resources

Other Names: I.O.U., Yindarlgooda, Lake Yindarlgooda, Boolong

Open Street Map: -30.727080649291626, 121.79271691259773

What3Words:///doorways.penalty.camouflages

Settled: 1893

Gazetted: 1895

Abandoned: ~1960s

Abstract

Bulong, a phantom township situated 20 miles east of Kalgoorlie, stands as a testament to the intoxicating volatility of the Eastern Goldfields, defined by two spectacular booms and two complete busts. Originally established as I.O.U. after the first rich gold lease was found around 1893, Bulong quickly blossomed into the principal civic center of North-East Coolgardie. The town boasted hotels, a brewery, a unique condensed water system, and high hopes—even being predicted to surpass Kalgoorlie. However, the ambitious gold rush collapsed swiftly, hastened by the failure and liquidation of a vital £70,000 tramway and battery project by 1897. Local government faded away by 1911. Decades later, Bulong witnessed a catastrophic modern revival: the Bulong Nickel Mine (1998–2003) failed due to unsuitable technology, leaving behind a massive environmental pollution problem and clean-up costs far exceeding the company’s bond. Today, Bulong is officially an abandoned town.

History

A Golden Promise: From I.O.U. to Bulong (1893–1896)

The history of Bulong begins, appropriately, with a debt—or at least the promise of one. While today the town is officially abandoned, having registered a population of zero in the 2016 census, its origins were rooted in the frantic pursuit of wealth on the Eastern Goldfields of Western Australia.2

It is said that gold was first discovered at Bulong by an Aboriginal man, Wimbah, who was also known as “Tiger” and that it was Wimbah who lead the Moher brothers, John and Thomas, to the discovery in 1893.3

By November 30, 1893, the I.O.U. lease (109E) was formally granted to a party including Kennedy, Hogan, Turnbull, Henry, and Holmes. Early production was encouraging, with Captain Matthews lodging 165 ounces of gold with the bank in May 1894. The gold was primarily found in “deep-leads” and alluvial workings, which, by 1900, had collectively yielded 17,500 ounces. This initial bounty spurred rapid development.4

At first the town was known by the name of its original mining lease, I.O.U., a name that ironically foretold the financial fate of many ventures launched there. The original name was changed to Bulong when it was gazetted in 1895. The name was taken from a nearby Aboriginal soak and was suggested by the surveyor, G Hamilton. 5

Economically, the area quickly proved its worth, featuring rich deposits such as the Queen Margaret mine, which generated considerable interest due to its phenomenally rich patches. So buoyant was the atmosphere that the prominent politician and “picturesque character,” Mr. F. C. Vosper, brazenly predicted a “brighter future for Bulong than for Kalgoorlie”.6

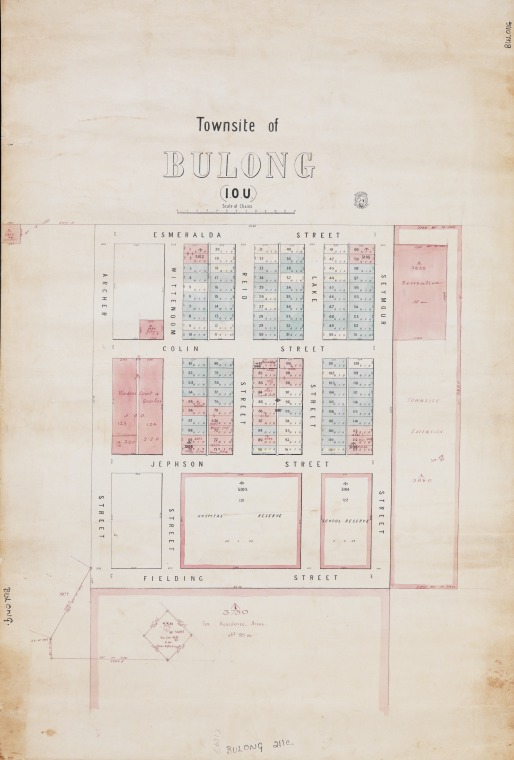

The original name, I.O.U., gave way to something more permanent. In October 1894, Surveyor G. Hamilton was instructed to lay out the townsite and, recognizing the need for a more suitable moniker, suggested “Boolong,” the Indigenous Australian name for a nearby soak or spring. By the end of 1895, the name had standardized to Bulong and the townsite was formally gazetted.7 8 9

At Its Zenith – The Town That Had It All (1896–1900)

In its brief heyday, Bulong transformed from a dusty mining camp into a substantial civic center, demonstrating remarkable energy and enterprise. By 1900, the population had swelled to 620, and 38,500 acres were held as leases.

Civic Structure and Social Life

Bulong established a robust local governance structure, becoming the principal township of North-East Coolgardie and hosting a warden’s court and police court for Government business. The Municipality of Bulong was established in 1896, and the Bulong Road District followed in 1899.10 11 12

The town offered all the amenities necessary for a busy, if isolated, life13 14:

- Commerce: Bulong featured six hotels—including the Bulong Hotel, the Court Hotel, the Globe Hotel, and the Grand Hotel—alongside three stores, bakeries, accountants, and butchers.

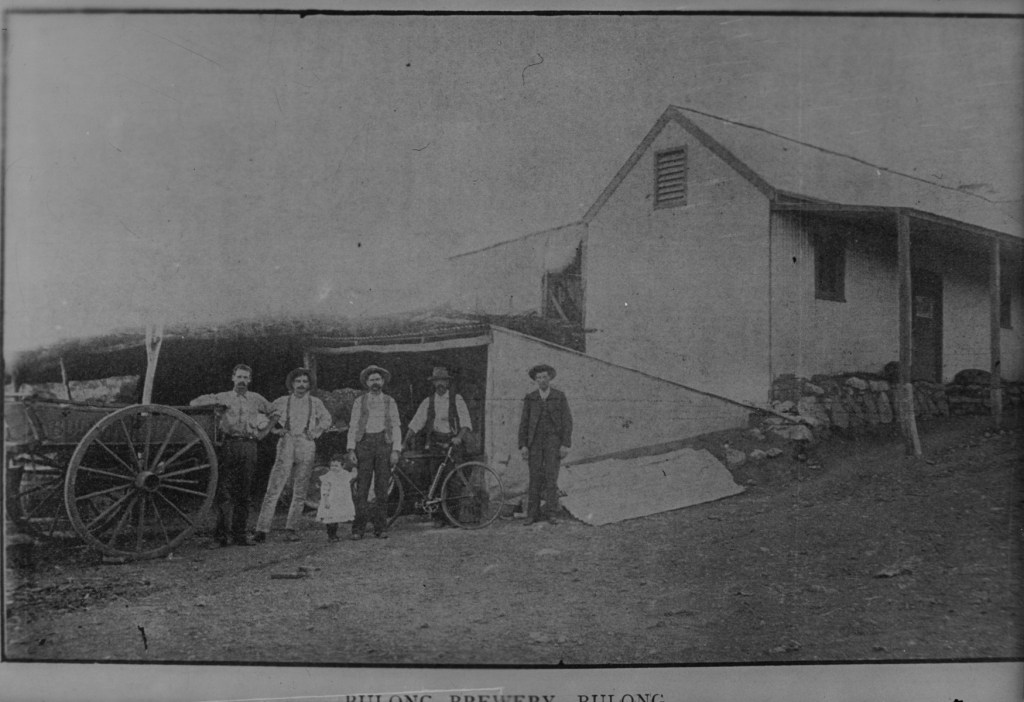

- Infrastructure: It boasted a hospital, a school, a town hall, a mechanics institute, multiple churches, a telegraph station, and the indispensable I.O.U. brewery, whose existence suggests that “thirst rather than enterprise may have given the impetus necessary”. The town even published its own newspaper, the Bulong Bulletin and Mining Register, from 1897 to 1898.

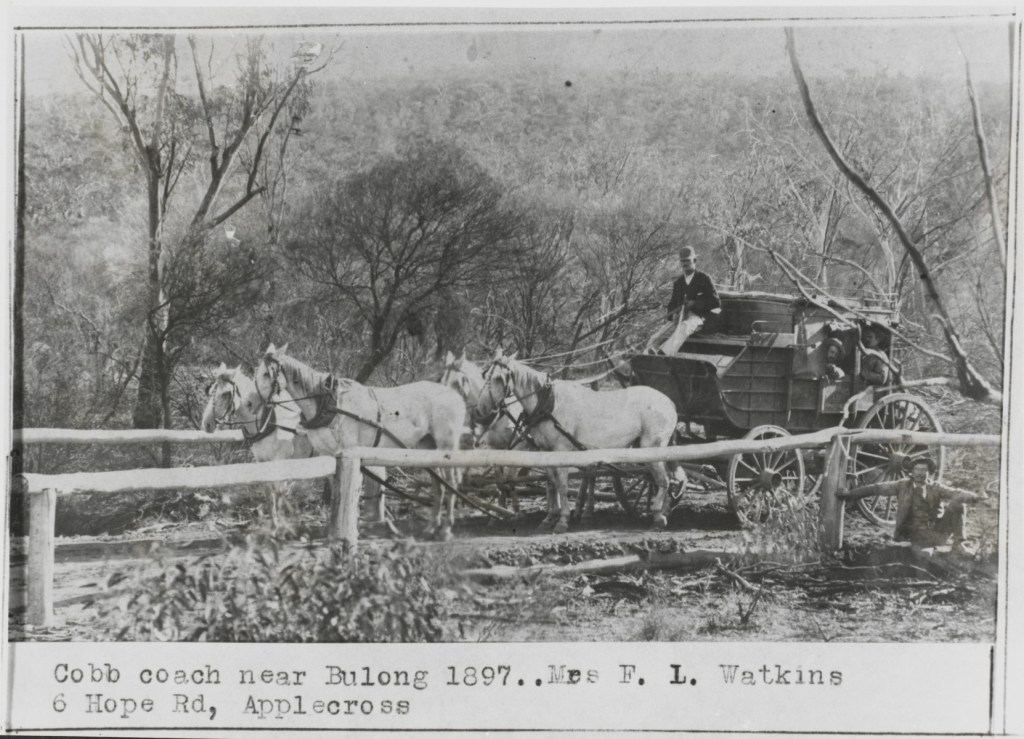

SLWA15

Socially, the community was vibrant, as reflected in the pages of its local paper. On a Sunday in October 1897, the Bulong Cricket Team kicked off the season in “real earnest” against the Federal C.C. from Hannatis. The visitors arrived at Greenwell’s Victoria Hotel via a six-horse drag. After the visitors amassed 140 runs for 4 wickets, the Bulong team, captained by Councillor Walker, opened the batting with a style of “real free batting” that contrasted sharply with the visitors’ “monotonous” play. Although Bulong was defeated by 57 runs, the rivals shared a “first-class dinner” at Greenwell’s Hotel, highlighting the lively social fabric of the goldfields.16

Environmental Ingenuity

Bulong was distinguished by its unique approach to the perennial problem of water scarcity. Its water supply was drawn from Lake Yindarlgooda, condensed on the lake’s banks, and then pumped to the top of Mount Stuart. From there, the water was distributed throughout the streets via gravity feed—a large-scale system for condensed water distribution that was rare in the region. Furthermore, the community made an effort to establish garden plots, constructing a large dam under Mayor R. C. Jones for irrigation. Crucially, the natural bush and timber surrounding the town were carefully preserved, lending the settlement a surprisingly “rural rather than a mining appearance,”17 deviating from the typical dusty look of goldfields settlements.18 19

The Sound of Silence: Logistical and Economic Failure (1897–1911)

Despite the civic achievements and initial gold yields, the foundation of Bulong’s economy was fragile, leading to an extremely swift collapse triggered by logistical failures.

The Tramway Debacle

The most ambitious infrastructural project, intended to cement Bulong’s economic future, was the Bulong Mining Tramway and Ore Reduction Company of Western Australia Limited. The London-formed company took over George Edmund Lane’s plan to connect the key leases, such as ‘The Last Chance,’ with a 40-head battery on Lake Bulong via a narrow-gauge tramline. The company spent an enormous sum, estimated at £70,000, on the works, which included 4 miles of 2ft gauge track, 48 trucks, and a small locomotive.20

However, the enterprise was doomed from the start. During an anticipated trial run, the small locomotive, nicknamed the “wild Irishman,” proved incapable of the task. It managed only about five miles per hour before stalling completely, forcing the prominent citizens and dignitaries who had taken seats in the trucks to abandon the trip and walk back to town to seek “liquid refreshment”. The company’s operations lasted less than two months, and it was in liquidation by the end of 1897.21

The Government Battery and Final Bust

The abrupt failure of the battery caused a massive shortage of ore treatment facilities, leading to the abandonment of many mines. The community petitioned the Government, which purchased the plant and machinery areas for £2,500 by August 1899. However, the Government Battery was plagued by difficulties: it struggled with water shortages, equipment failure, and bad road conditions that inflated cartage costs by 40 percent. Despite initially crushing thousands of tons of ore, the battery’s most productive year saw activity drop drastically towards the end. Compounding the problem, the Government decided against purchasing the failed tramway, recognizing that its limited route did not suit the majority of Bulong’s mines.

By February 1900, crushing was suspended, and the State Battery was quickly dismantled and relocated to other goldfields like Widgiemooltha and Mulline. With the means of processing ore gone and the field proving incapable of supporting continuous deep mining, Bulong’s economic existence was effectively over.22

Civic Dissolution

The social and civic structures, which had been so enthusiastically established, soon crumbled. The Municipality of Bulong voluntarily amalgamated with the Bulong Road District in December 1909 for reasons of economic efficiency. This administrative body itself lasted only until June 9, 1911, when it was formally merged into the larger Kalgoorlie Road District, signaling the complete abandonment of local self-governance. The only lasting physical relics of the early industrial failure remain the impressively constructed high embankments and cuttings of the short-lived tramway formation, which still exist in the hilly country near Lake Yindarlgooda.23 24

A Second Death: The Modern Environmental Legacy

After the gold rush era (c. 1893–1908) faded, Bulong lay dormant for decades. The final traces of its function, such as the woodline railway that ran through the townsite, were removed by 1920, and the post office closed in 1956.25

However, Bulong was destined for a second, equally disastrous, boom-bust cycle in the late 20th century. The area, adjacent to Lake Yindarlgooda, became the site of the Bulong Nickel Mine, a surface nickel and cobalt laterite deposit. The project, whose foundation stone was laid in 1997, was hailed as a key development in a “new generation of nickel mines in WA”.26

The Nickel Mine Catastrophe (1998–2003)

The project, which Preston Resources bought for A$319 million in 1998, operated for only four years (1998–2003) and was an unmitigated financial failure. The operational collapse was primarily an environmental and technical one.27

- Technical Flaw: The process plant was designed to use a pressure acid leach process, a method found to be unsuitable for the specific Western Australian laterite deposits.

- Environmental Cost: The ore’s low nickel grade (one percent) and high magnesium impurities (five percent) necessitated the use of staggering amounts of sulphuric acid—up to 500 kilograms per tonne of ore—significantly exhausting the available acid supply in the state. This immense acidity damaged the process plant, while clay in the ore “bogged up” the system, and gypsum caused calcium build-up in the pipes.

- Financial Collapse: The operation accumulated $A700 million in debt and resulted in an estimated $A300 million loss for Barclays and bondholders who took over the project. Mining operations were suspended in May 2003.

The most lasting consequence of the modern bust is its environmental pollution legacy. In April 2016, clean-up costs were estimated to reach $A6.8 million, far surpassing the meagre $A1.12 million bond collected from the former owners. Concerns over the abandoned tailings storage facility and evaporation ponds, and their impact on Lake Yindarlgooda, spurred a massive 900-page government investigation report published in 2021.28

mindat.org29

Bulong remains an abandoned town. Its history, spanning two centuries of mining ambition, confirms that while gold and nickel promise wealth, logistics, environment, and engineering ultimately dictate success, or in Bulong’s case, spectacular failure.

Timeline

- 1893 (August–December): Gold discovered, leading to the I.O.U. lease.

- 1893 (November 30): The I.O.U. lease (109E) is formally granted.

- 1894 (October): Surveyor G. Hamilton suggests changing the name from I.O.U. to Bulong (Indigenous name for a nearby soak).

- 1895: The townsite of Bulong is formally gazetted.

- 1896 (January 2): Bulong Post Office opens.

- 1896: The Municipality of Bulong is established.

- 1897 (Early): Construction begins on the Bulong Mining Tramway (2ft gauge) by the London-based Ore Reduction Company.

- 1897 (October 6): The Bulong Bulletin and Mining Register records a cricket match against the Federal C.C..

- 1897 (November): The Ore Reduction Company battery starts crushing; the inaugural tramway trip fails spectacularly due to the locomotive stopping.

- 1897 (End): The Bulong Mining Tramway and Ore Reduction Company, having spent £70,000, enters liquidation after operating for less than two months.

- 1897–1898: The Bulong Bulletin newspaper is published.

- 1899 (March 1): The Government Battery (purchased to save the field) begins public crushing, but struggles with operational issues and water shortages.

- 1899 (December 20): The Bulong Road District is formally established.

- 1900: Town population peaks at 620. Dismantling and relocation of the Government Battery begins due to poor output.

- 1908: The goldfield’s main period of activity largely ends.

- 1909 (December 10): The Municipality of Bulong is absorbed by the Bulong Road District for economic reasons.

- 1911 (June 9): The Bulong Road District is merged into the Kalgoorlie Road District, ending Bulong’s local government.

- 1920: The last rails of the woodline railway that ran through the townsite are lifted.

- 1956 (August 30): The Bulong Post Office closes.

- 1978: The laterite nickel and cobalt deposit is discovered by WMC Resources.

- 1998–2003: The Bulong Nickel Mine operates, failing spectacularly due to the unsuitable pressure acid leach process and huge sulphuric acid demand (500kg/tonne of ore).

- 2003 (May): Nickel mining operations are suspended as the company goes into receivership.

- 2014: Wingstar Investments purchases the mine.

- 2016: Bulong is recorded as having a population of 0.

- 2021: A 900-page government report is published, investigating the environmental impact of the abandoned mine facilities on Lake Yindarlgooda.

Map

Sources

- SLWA, 2025. Stevenson, Kinder & Scott photograph collection ; BA1119/P1343-6. Retrieved 23 Nov 2025 from https://encore.slwa.wa.gov.au/iii/encore/record/C__Rb3096522 ↩︎

- Wikipedia, 2025. Bulong, Western Australia. Retrieved 23 Nov 2025 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bulong,_Western_Australia ↩︎

- HISTORY OF I.O.U. AND BULONG (1952, June 16). Kalgoorlie Miner (WA : 1895 – 1954), p. 9. Retrieved December 6, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article256892502 ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎

- Whiteford, David, 2010. Bulong’s Battery, boom to bust. Retrieved from Outback Family History on 30 Nov 2025 from https://www.outbackfamilyhistoryblog.com/bulongs-battery-boom-to-bust-by-david-whiteford/ ↩︎

- Kalgoorlie Miner, 1952: refers to early optimism and growth ↩︎

- Wikipedia, Bulong: refers to gazetting of Bulong ↩︎

- Moya Sharp, n.d. Bulong-Western Australia. Retrieved 27 Nov 2025 from https://outbackfamilyhistory.com.au/records/record.php?record_id=73&town=Bulong ↩︎

- Kalgoorlie Miner, 1952: refers to early growth and gazetting ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Wikipedia, Bulong: refers to local administration ↩︎

- Wikipedia, 2025. Bulong Road District. Retrieved 30 Nov 2025 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bulong_Road_District ↩︎

- Kalgoorlie Miner, 1952: refers to establishment of facilities ↩︎

- Wikipedia, Bulong: refers to establishment of facilities ↩︎

- State Library of Western Australia, n.d. Bulong Brewery [picture]. Retrieved 6 Dec 2025 from https://encore.slwa.wa.gov.au/iii/encore/record/C__Rb2357406 ↩︎

- SPORTING, (1897, October 6). Bulong Bulletin and Mining Register (WA : 1897 – 1898), p. 3. Retrieved December 6, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article251548801 ↩︎

- Whiteford, 2010:refers to Bulong appearance ↩︎

- Kalgoorlie Miner, 1952: refers to the use of technology to improve life on the goldfields ↩︎

- Wikipedia, Bulong: refers to businesses and support services ↩︎

- Whiteford, 2010: refers to tramway proposal ↩︎

- ibid: refers to failure of tramway ↩︎

- ibid: refers to failure of battery ↩︎

- ibid: refers to amalgamation and subsequent of admistrative bodies ↩︎

- Wikipedia, Bulong Road District: refers to closure ↩︎

- Wikipedia, Bulong: refers to closure and removal of railway ↩︎

- Wikipedia, 2025. Bulong Nickel Mine. Retrieved 6 Dec 2025 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bulong_Nickel_Mine ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- mindat.org, n.d. Bulong Ni Mine, Bulong Goldfield, Kalgoorlie-Boulder Shire, Western Australia, Australia. Retrieved 6 Dec 2025 from https://www.mindat.org/loc-271527.html ↩︎

Further Reading

- Bulong’s First Cemetery

- Outback Family History – Bulong

- Bulong Road District

- Bulong Nickel Mine

- State Records Office of WA – Bulong

- State Records Office of WA – I.O.U.

- SLWA – Catalogue search

- SLWA – 1916 Town Plan of Bulong

- Morawa District Historical Society – Ghost Towns of Western Australia

- Daphne Popham, “Reflections: Profiles of 150 women who helped make Western Australia’s history”. In particular, p.56 Elizabeth Halford.

- The Goat Lady – Hilda Jarvis