Demographics

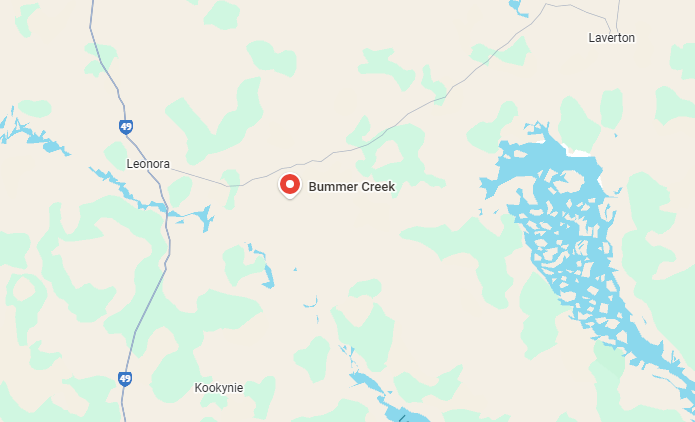

Region: Goldfields-Esperance

LGA: Leonora

Industry: Gold Mining

Other Names: Mia Katara, Quatara, Bummer’s Creek, Bummer Creek

Open Street Map: -28.552324786138982, 121.664240666773

What3Words: ///puny.meanest.mistaking

Settled: 1895

Gazetted: N/A

Abandoned: 1917

Abstract

Bummers Creek, located in the hot desert climate of Western Australia near Menzies and Leonora, exploded into existence in the mid-1890s following spectacular gold discoveries. Established primarily as a quartz mining settlement, the boom was driven by finds like the “Twilight” specimen, estimated to contain 200 ounces of gold, and sustained by enterprises such as Australia United, Ltd., which processed thousands of tons of ore. The community quickly established a social fabric centered around the comfortable Welcome Hotel and a busy race track. Crucially, the presence of Afghan cameleers defined the social and economic landscape, as they established essential market gardens and utilized the area as a vital depot. However, the harsh environment was unforgiving: thirst claimed lives in the earliest days, and a catastrophic flood in March 1907 decimated the town’s infrastructure, washing away the gardens and heavily damaging the hotel. Though some activity, supported by the Afghan community, persisted into the 1920s, Bummers Creek soon faded from its brief glory, leaving today “virtually nothing to be seen” of its former life.

History

In the arid heart of Western Australia, approximately 30 kilometres northeast of Leonora, lies the ephemeral ghost of Bummers Creek.1 Today, the place is notoriously difficult to locate, and even upon reaching the site, a visitor finds “virtually nothing to be seen of its former glory”. Yet, for a vibrant, if brief, period spanning the turn of the nineteenth century, Bummers Creek was a fierce nexus of gold, ambition, and grueling hardship, reflecting the intense and often brutal history of the Western Australian goldfields. Born of sudden mineral wealth and defined by its desperate struggle against a hot desert climate,2 Bummers Creek represents the ultimate boom and bust of the desert gold rush.

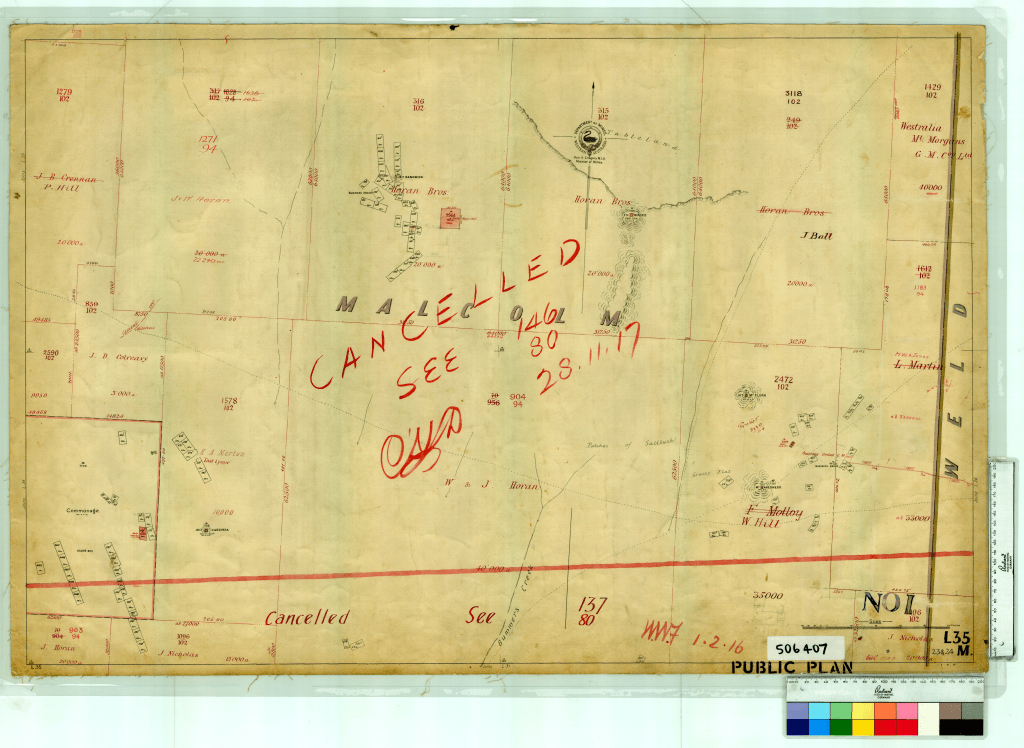

(Zoom in to see the Creek at the bottom of the plan in the centre)

State Records Office of WA3

The Sun Rises on a Rich Find

The origin story of Bummers Creek is intrinsically linked to the dazzling, hard-won promise of gold. Though prospectors were already risking life and limb throughout the goldfields, Bummers Creek achieved prominence in late 1896 through a discovery reported near Menzies.4

The initial find was made by two prospectors, Johnston and his mate, who were working on the nearby Carnegie lease. Toward the end of December, one Sunday afternoon, they stumbled upon a small specimen, stimulating a deeper search. Following the floating pieces of quartz up the hillside, they located a rich cap, from which they picked a considerable body of stone, including some exceedingly rich pieces. This find, quickly protected by pegging the ground, was christened the Rising Sun claims.

The richness of the quartz specimens was astonishing, though initially, the deposit had been misidentified as alluvial. Johnston arrived in Coolgardie soon after with specimens estimated to contain between 400 and 600 ounces of gold. Among these, the largest piece, dubbed Twilight because it was discovered just at sunset, weighed 295 ounces and was calculated to hold 200 ounces of the precious metal. These samples, composed of pure gold in a matrix of quartz ironstone, were proudly displayed at the Union Bank in Coolgardie and were heralded as the richest seen there yet.5

The early economic landscape was chaotic, spurred by initial hope. By January 1897, the lure was significant enough that 600 ounces of alluvial gold were found, and a forty-five-ounce nugget was pulled from the earth by Jim Bryan.6 However, even during the rush, only thirty or forty men were working the alluvial ground, and they were “not meeting with exceptional success”. The true value lay deeper in the quartz reefs. Subsequent crushing proved the economic viability of the reef, even where miners were skeptical. On the Possible lease, owned by Johnstone and party, a rich leader had already yielded about 2,000 ounces of gold via dollying. When they finally tested what they thought was merely “casing” or mullock, it turned out to be lode formation. A trial lot of 20 tons from the dump produced a stellar 108 ounces of smelted gold, confirming that a “certain fortune” awaited the owners should the lode prove to be eight feet wide.7

The Social Fabric

bonzle.com8

As the mining enterprise took hold, Bummers Creek developed a tangible, if rough-hewn, social and economic identity far beyond a simple scattering of tents. The Welcome Hotel, constructed in 1896, formed the nucleus of the nascent community. Run by H.C. Hendrickson and Mr. Murdoch, the hotel was renowned for its comfort and was described as being “tastefully furnished with table silver well above that seen in the usual country hotel”. Its windows offered views onto the local attraction: the Bummers Creek Race Track, a wide course approximately three-quarters of a mile around.9

The social life was robust. A large fourteen-event race meeting was held around Christmas 1897. Later, in January 1900, the Hotel Sports Ground hosted a successful sports meeting featuring foot racing and other athletic events, which served the vital purpose of raising funds for the Mount Malcolm District Hospital. The community also managed to host a remarkable “Record Christening” event at the hostelry in November 1905, where fifteen babies were baptized in a single day.10 11

On the commercial front, the scale of development progressed from individual efforts to corporate ventures. By December 1898, the company Australia United, Ltd., Bummers Creek, reported impressive crushing results, having processed 149 tons that yielded 298 ounces and 10 pennyweights of gold. Their total production to date stood at 2,965 tons, yielding 6,836 ounces, 17 pennyweights, and 5 grains of gold. This output solidified Bummers Creek’s position as a significant economic node within the goldfields of the Malcolm district.

The Cameleers

A defining social and economic characteristic of Bummers Creek was the profound influence of the Afghan cameleers. They were instrumental in developing the goldfields, setting up camel depots and camps, and providing crucial transport and logistical support throughout Western Australia.12

SLWA13

At Bummers Creek, the Afghan community established a substantial presence. They built one of the seven small mosques recorded throughout the goldfields between the 1890s and 1910s. More uniquely, they successfully mastered agriculture in this hot desert climate.14 As early as 1896, Afghan Salley Mahomed maintained a vegetable garden. Gool Mahomet and his wife Adrienne later established market gardens 1.5 miles from the Welcome Hotel, where they grew melons and vegetables, and sold vital water and wood to local miners. They maintained two wells on the creek bank and three others for irrigating their produce, transforming the harsh landscape into what was likely perceived as an “Oasis in the Desert”. The presence of these businesses is further cemented by livestock brand registrations made by residents like Mea Jan and Juma Khan in 1912 and 1924, respectively.15 16 17

However, the utilization of the environment created social friction. In August 1897, a correspondent lamented that the place was “overrun with hundreds of diseased and mangy camels”. Owners of these herds, particularly Afghans, considered Bummers Creek their “spelling ground,” or rest area. This practice consumed critical “feed and water… at the cost of the travelling public and prospectors,” highlighting a severe resource conflict in the arid region.18

The Inevitable Decline

The same harsh environment that made the Afghan gardens so essential ultimately began to erode the life of the settlement. The hot deserts climate proved merciless to prospectors. In January 1895, before the rich reef finds fully kicked off the boom, Albert Loechner (Lockner), a prospector seeking fortune for his family, died of apparent suicide near Bummer’s Creek, believing himself to be dying of thirst, tragically close to a chain of waterholes.19 Nine years later, in April 1904, Patrick Dynan died of thirst in the bush after setting out from Bummers Creek for Anaconda.20 The two known historical burials in the immediate area – Loechner (1895) and John Ryan (1898)21 – were never formally registered, becoming classed as lonely graves.

The fatal blow to the settlement’s infrastructure came not through drought, but through sudden, catastrophic inundation. In March 1907, the Malcolm district experienced its most disastrous flood. Heavy rain caused all creeks to run a banker. At Bummers Creek, the environmental damage was immediate and widespread: the Afghans’ beautiful gardens were entirely swept away, resulting in the destruction of “hundreds of pounds’ worth of vegetables, fruit trees and property”. Mrs. Moore’s hotel was severely damaged, with six or seven rooms scattered along the creek banks, leaving only two rooms standing. Mrs. Moore and her family narrowly escaped by spending the night on the roof.22

The 1907 flood marked a critical turning point. While some camel-related activity was still recorded in the 1920s23, the Afghan market gardeners, such as Gool Mahomet and his family, relocated between 1915 and 1917, seeking opportunities elsewhere.24 Without continuous rich new finds to offset the severe operational risks posed by the climate—both drought and deluge—the intensive, capital-heavy quartz mining operations could not sustain a permanent populace. The town was never formally gazetted, and as the gold yield tapered off, the buildings decayed and the residents drifted away.25

Bummers Creek Today

Bummers Creek’s legacy lingers today, albeit in an administrative capacity. In 2009, the Bummer Creek area on the Leonora-Laverton Road was cited for an instance of environmental non-compliance concerning Aboriginal heritage during Main Roads projects26, a quiet acknowledgment of the historical landscape that remains sensitive long after the last gold miner departed. The history of Bummers Creek is a stark illustration that in the Western Australian desert, fortune was always fleeting, and the environment, whether dry or flooded, was the ultimate victor.

Timeline

- 1895 (January): Prospector Albert Loechner dies near Bummers Creek, believed to be due to thirst.

- 1896: Welcome Hotel is built by H.C. Hendrickson and Mr. Murdoch. Afghan Salley Mahomed establishes a vegetable garden.

- Late 1896 (December): Prospectors Johnston and mate discover the rich quartz cap, leading to the establishment of the “Rising Sun claims”. The massive “Twilight” specimen, estimated to hold 200oz of gold, is discovered.

- 1897 (January): Discovery of 600 ounces of alluvial gold; Jim Bryan finds a 45-ounce nugget.

- 1897 (March): The rich quartz find is widely reported, dispelling initial rumors of alluvial wealth; 30-40 men are reported to be working the alluvial.

- 1897 (August): Concerns are raised that hundreds of diseased and mangy camels, primarily belonging to Afghans, are overrunning the area and consuming valuable resources.

- 1897 (August): Rich lode formation is discovered on the Possible lease, yielding a trial crush of 108oz of smelted gold from 20 tons.

- 1897 (Christmas): A large, 14-event race meeting is held at the Bummers Creek Race Track.

- 1898 (July): Alfred and Mary Armstrong are married at Bummers Creek.

- 1898 (December): Australia United, Ltd., reports crushing 149 tons for 298oz 10dwt of gold.

- 1890s–1910s: A mosque is established by the Afghan cameleer community.

- 1900 (January): A successful sports meeting is held at the Hotel Sports Ground to raise funds for the Mount Malcolm District Hospital.

- 1904 (April): Patrick Dynan dies of thirst in the bush after leaving Bummers Creek.

- 1905 (November): A record christening event, involving fifteen babies, is held at the Bummer’s Creek hostelry.

- 1907 (March): A disastrous flood sweeps through Bummers Creek, destroying the Afghan market gardens and severely damaging Mrs. Moore’s hotel.

- 1915–1917: Afghan market gardeners, such as Gool Mahomet and his family, leave the settlement.

- 1924: Livestock brand registrations for camel operators like Juma Khan and Mea Jan indicate some continued Afghan presence.

- 2009: The Bummer Creek area is cited for environmental non-compliance related to Aboriginal heritage during road works on the Leonora-Laverton Road.

- Present Day: Bummers Creek is described as having “virtually nothing to be seen of its former glory,” with two known burials classed as lonely graves.

Map

Sources

- Moya Sharp, n.d. Bummers Creek – Western Australia AKA Quatata & Mia Katara. Retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from https://www.outbackfamilyhistory.com.au/records/record.php?record_id=74 ↩︎

- mindat.org, n.d. Bummer Creek, State of Western Australia, Australia. Retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from https://www.mindat.org/feature-2075440.html ↩︎

- State Records Office of Western Australia, 1917. 40 Chain L Plan [Tally No. 506407. Cartographic material retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from https://archive.sro.wa.gov.au/index.php/40-chain-l-plan-tally-no-506407-l35-23-24m ↩︎

- THE BUMMER’S CREEK DISCOVERY. (1897, March 12). The Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA : 1855 – 1901), p. 1. Retrieved December 5, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66521367 ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎

- Sharp: refers to Bryan’s nugget ↩︎

- Bummer’s Creek. (1897, August 23). The Miners’ Daily News (Menzies, WA : 1896 – 1898), p. 2. Retrieved December 5, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article257490358 ↩︎

- Bonzle.com, 1990. Bummers Creek Hotel. Photo of unknown origin donated by Bulfrog99 to bonzle.com retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from http://203.30.79.121/c/a?a=p&i=554&j=554&x=121%2E683585&y=%2D28%2E794805&w=43384&d=pics&c=1&p=203448&mpsec=0 ↩︎

- Sharp: refers to the Welcome Hotel and race track ↩︎

- ibid: refers to fundraising at track meeting ↩︎

- A RECORD CHRISTENING. (1905, November 18). Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 – 1954), p. 26. Retrieved December 5, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article37809765 ↩︎

- Embassy of The Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, 2020. Afghans, Islam and Australia: From Cameleers to the Present Day. Retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from https://www.afghanembassy.au/news/afghans-islam-and-australia-from-cameleers-to-the-present-day.html ↩︎

- State Library of Western Australia, 2024. Sheiks, Fakes & Cameleers: An Afghan at Bummers Creek 1909. Photo, B&W, 4890B/20, retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from https://slwa.wa.gov.au/whats-on/sheiks-fakes-cameleers-0 ↩︎

- mindat.org: refers to climate ↩︎

- Sharp: refers to Afghan vegetable and market gardens ↩︎

- Farina Restoration Project Group, 2025. Gool Mahomet and Adrienne Lesire. Retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from https://farinarestoration.com/history/gool-mahomet/ ↩︎

- Carnamah Historical Society & Museum, n.d. WA Livestock Brands 1912-1962: Bummers Creek. Retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from https://www.carnamah.com.au/livestock-brands?keyword=Bummers+Creek ↩︎

- Bummer’s Creek. (1897, August 23). The Miners’ Daily News (Menzies, WA : 1896 – 1898), p. 2. Retrieved December 5, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article257490358 ↩︎

- Colac & District Family History Group Inc, n.d. A Tailor’s Tragic Journey. Retrieved 5 Dec 2025 https://www.colacfamilyhistory.org.au/about/newsletter/a-tailors-tragic-journey/ ↩︎

- Outback Graves Markers, 2025. Patrick DYNAN. Retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from https://outbackgraves.org/burial-records/person/511 ↩︎

- ibid: John RYAN. https://www.outbackgraves.org/burial-records/person/955 ↩︎

- FLOODS IN THE MALCOLM DISTRICT. (1907, March 26). Kalgoorlie Western Argus (WA : 1896 – 1916), p. 11. Retrieved December 5, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article33087291 ↩︎

- Carnamah: refers to registrations in the 1920s ↩︎

- Farina: refers to Mahomet family ↩︎

- Morawa District Historical Society, n.d. The Ghost Towns and Wayside Inns of Western Australia: Bummers Creek. Retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from https://morawamuseum.org.au/ghosttowns/B.pdf ↩︎

- Parliament of Western Australia, 2013. Parliamentary Questions: Question on Notice No 638. Retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from https://www.parliament.wa.gov.au/parliament/pquest.nsf/3f9c0f35f2b504544825718e001105c9/22c0ab81151acda748257c2f00172e83?OpenDocument ↩︎

Further reading

- State Records Office of WA

- “At Bummer’s Creek” [poem] by John Philip Bourke, 1860-1914

- “Progress at Bummer’s Creek” [poem] by The Battler

- “Hotel at Bummers Creek completed. Publican to start a vegetable garden.” (Golden Age newspaper on microfilm)