Region: Pilbara

LGA: City of Karratha

Industry: Pearling

Other names: Tien Tsin, Jarman Island, Butcher’s Inlet

Traditional name: Bajinhurrba

Open Street Map: -20.6783830, 117.1886006

What3Words: ///swept.hotdogs.vans

Settled: 1863

Gazetted: 1873

Abandoned: by 1950s

Abstract

Cossack, a historic ghost town located at the mouth of the Harding River in Western Australia’s Pilbara region, possesses a rich and complex history beginning in 1863 when it was established as Tien Tsin Harbour. The site is also known by the Ngarluma name Bajinhurrba. Renamed Cossack in 1872 after the visiting vessel HMS Cossack, it quickly became the first port in the North West and the birthplace of the region’s pearling industry. The town boomed from pearling and gold discoveries, fostering a deeply multicultural society that included significant populations of Aboriginal people and Asian migrants. Its eventual demise was driven by environmental factors—the silting up of the harbor—and economic shifts, such as the relocation of the pearling fleet to Broome and the construction of a new port at Point Samson. Abandoned by the 1950s, later restoration efforts transformed it into a heritage precinct. However, current operations remain precarious due to infrastructure deficits and management disputes, resulting in the recent closure of most tourism facilities.

History

Cossack, nestled on the Pilbara coast near the mouth of the Harding River, is a physical embodiment of Western Australia’s colonial frontier past. Today, the immaculately restored bluestone structures stand against a vast, arid landscape, testifying to a fleeting era when this secluded spot was the economic powerhouse of the North West. The history of Cossack is a saga of ambition, resilience, and profound social complexity, tracking its transformation from Indigenous heartland to booming port, and finally, to a protected ghost town repeatedly struggling for sustained life.1 2 3 4 5

Indigenous Foundations and European Arrival

Long before European settlement, the land surrounding the Harding River mouth, known to the Ngarluma people as Bajinhurrba, was an important cultural site. Archaeological evidence and rock art attest to the enduring presence of the Ngarluma, the traditional owners, whose connection to the landscape spans tens of thousands of years.6 7 8

The European history of the site began abruptly in May 1863, following explorer Francis Gregory’s favourable reports on the region’s pastoral potential in 1861. Walter Padbury, often credited as the first European settler, landed his stock and party here, naming the nascent settlement Tien Tsin Harbour after his vessel, the barque Tien Tsin. This marked the establishment of the first port in the North West. The area was also historically referenced as Port Walcott or Butcher Inlet. The name that stuck, Cossack, was officially adopted in 1872 (or 1873), chosen in honour of the visiting warship HMS Cossack, which carried Governor Frederick Weld in December 1871.9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

The Boom Years: Pearling, Pastoralism, and Gold

Cossack’s early economic life was defined by its status as a critical port supporting the pastoral industry, facilitating the transport of essential supplies and outgoing wool clips for the emerging settlement of Roebourne. However, the true source of its boom was the pearling industry, which commenced in 1864.17 18 19

By the early 1870s, up to 80 luggers were operating out of the burgeoning port.20 21 This industry shaped the social and economic fabric of the town in profound and often troubling ways. The demand for labor outstripped the local supply of European settlers, leading to reliance first on local Aboriginal people, including women and children, for pearling work.22 23 24 Police records document the high mortality rates among Indigenous pearl divers, often dying from conditions like “inflammation of the lungs,” attributable to overexertion in the water. 25 This system involved coercion and outright abduction of Aboriginal people from as far as the Gascoyne and Kimberley regions, a labor system described by one historian as akin to slavery.26 27

As the pearling industry expanded, Cossack transformed into a deeply multicultural community, attracting thousands of workers from across the Indian Ocean rim.28 29 By the 1870s and 1880s, the population included large numbers of Malays, Japanese, Chinese, Filipinos, and Koepangers (Timorese).30 This ethnic diversity, however, was accompanied by severe segregation. The majority of the non-European population lived in an enclave known as “Chinatown,” “Japtown,” or “Malaytown,” typically described as a crowded and rough area of shanties located away from the main European town core. Despite this segregation, Asian migrants made vital economic contributions, establishing businesses like Chinese bakeries and market gardens that supplied fresh produce to the European settlers in the harsh environment.31 32 33 34

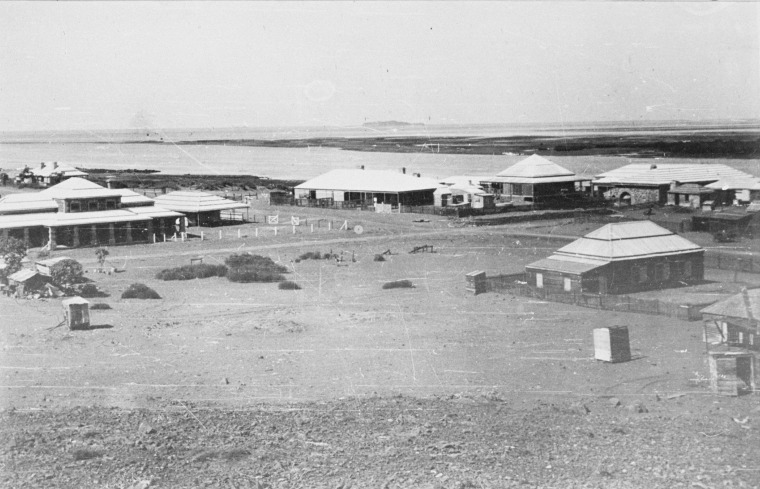

SLWA35

The fortunes of Cossack further swelled with the discovery of gold in the Pilbara region in 1887, cementing its role as an essential staging post for prospectors.36 37 The economic confidence of this period fueled civic development. Permanent structures were constructed of durable materials like local bluestone (ironstone rock) and ballast rock brought by ships, intended to withstand the tropical climate. These included major government buildings like the imposing Courthouse, Customs House and Bond Store, and Police Quarters, many designed by Chief Architect George Temple Poole. The design of these solid stone buildings reflected a necessary architectural adaptation to the frequent cyclonic conditions.38 39

SLWA40

Furthermore, infrastructure improved significantly in response to the challenging geography. An initial causeway linking Cossack to Roebourne in 1870 was eventually replaced by a horse-drawn tramway completed in 1887, facilitating movement across the tidal flats.41

Environmental and Economic Decline

Cossack’s period of flourishing prosperity was short-lived, beginning its rapid decline soon after the turn of the century, roughly four decades after its establishment. The demise was driven by a combination of environmental constraints and external economic pressures.42

- Environmental Impact: The port suffered from a persistent natural problem: silting.43 The accumulation of silt at the mouth of the Harding River eventually rendered the harbour unsuitable for the larger, more modern ships entering the region in the early 1900s. Goods had to be ferried via lighters from vessels anchored several miles offshore, making the port increasingly inefficient.44 45

- Economic Shift: Concurrently, the original pearling grounds became depleted, and the main pearling fleet officially shifted its operational base north to Broome by 1886 and 1900. The impetus from the Pilbara goldfields also waned as new gold discoveries were made elsewhere in the state. Responding to the port’s redundancy, the government developed a new jetty at Point Samson between 1902 and 1904, and all shipping movements were subsequently relocated there. The formal consequence of these shifts was the dissolution of the Municipality of Cossack in 1910.46 47 48

Subsequent Attempts at Revival and Abandonment

In the years following its abandonment as a major port, several attempts were made to repurpose the townsite. The former Bond Store, a solid structure designed by George Temple Poole, was converted in the 1930s into a turtle soup factory by Monte Bello Sea Products Limited, but this enterprise failed by 1935.49 50

A darker period saw the establishment of a lazarette (leprosarium), gazetted as a quarantine reserve adjacent to Cossack on the opposite bank of the Harding River in 1913, and operating until 1931. This facility housed patients, particularly Aboriginal people, who were often forcibly removed from their communities under the Aborigines Act 1905. Reports indicate harsh conditions at the camp, with Aboriginal patients often forced to build their own huts while non-Indigenous patients were afforded decent accommodation, highlighting a stark disparity and contributing to the site’s history of trauma related to colonization.51 52

The Japanese community, which had achieved economic prominence, owning key properties like the North West Mercantile Store through figures like merchant Jiro Muramats, remained until World War II. At the outbreak of the war, the Japanese residents were interned, a final blow to the viability of the hamlet. Though some individuals stayed until after the war, by the early 1950s, Cossack was completely abandoned, becoming an official ghost town.53

The Rebirth as a Heritage Precinct

The structural ruins and historical importance of Cossack prompted civic interest in the 1970s. The Cossack Project Committee was formed to restore the town and promote it as a tourist attraction. The main buildings, constructed of resilient stone, were the focus of restoration works initiated in 1979 and completed by 1991. The precinct was eventually declared a museum town and was listed on the State Register of Heritage Places.54

The restoration allowed these historic assets to take on new life, forming the cornerstone of cultural tourism. The former Courthouse became a museum, the Police Barracks was converted into budget accommodation, and the Customs House and Bond Store functions as a café and exhibition venue. Today, Cossack is celebrated for annually hosting the prestigious Cossack Art Awards, using the historic bluestone buildings as gallery space and attracting thousands of visitors each winter.55 56 57

The Struggle for Sustainable Activation

Despite its rich history and aesthetic value, sustained activation remains challenging. Infrastructure deficiencies, such as the lack of adequate power and water services, have hindered full development. In 2020, management responsibilities were transferred to the Ngarluma Yindjibarndi Foundation Ltd (NYFL) with the hope of revitalizing the site through indigenous custodianship and eco-tourism. However, in April 2024, citing years of unfulfilled promises and bureaucratic delays by the State Government in securing permanent tenure and necessary licenses, NYFL closed its operations, resulting in the temporary closure of the cafe, museum, and campgrounds.

The site’s rich archaeological record, encompassing Aboriginal, Asian, and European remnants, remains nationally significant. While the heritage trails and fishing wharf remain open, Cossack’s ongoing struggle for sustainable economic footing reflects the challenges faced by remote historical sites, perpetually caught between celebrating its complex heritage and securing a viable future.58

Published: 29 December 2023

Updated: 12 December 2025

By Christine Harris

Sources

- Aussie Towns, 2021. Cossack, WA. Retrieved 15 Sep 2023 from https://www.aussietowns.com.au/town/cossack-wa ↩︎

- Australia’s North West, 2025. Cossack. Retrieved 10 Dec 2025 from https://www.australiasnorthwest.com/explore/pilbara/cossack/ ↩︎

- TPG Place Match, 2018. Cossack Draft Volume 1: Conservation Management Plan. p.v Executive Summary. Retrieved 10 Dec 2025 from https://www.karratha.wa.gov.au/sites/default/files/uploads/20180213%20Cossack%20CMP.pdf ↩︎

- ibid: p.vi ↩︎

- ibid: p.16 ↩︎

- Wikipedia, 2025. Cossack, Western Australia. Retrieved 10 Dec 2025 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cossack,_Western_Australia ↩︎

- Jake Dietsch, 2024. The West Australian: Pilbara ‘ghost town’ Cossack closes as traditional operators blame Department of Lands. Published online 20 Apr 2024. Retrieved 10 Dec 2025 from https://thewest.com.au/politics/state-politics/pilbara-ghost-town-cossack-closes-as-traditional-operators-blame-department-of-lands-c-14250349 ↩︎

- TPG: p. 11 – refers to pre-colonial occupation ↩︎

- Alex Kopp, n.d. From Asia to Cossack: Education Package for Years 5 and 6 HASS. p.1. Retrieved 10 Dec 2025 from https://karratha.wa.gov.au/sites/default/files/uploads/LHO-Yr5-6_From_Asia_to_Cossack.pdf ↩︎

- TPG: p.12 – refers to early European exploration ↩︎

- WA Now and Then, n.d. Cossack. Retrieved 10 Dec 2025 from https://www.wanowandthen.com/Cossack.html ↩︎

- Wikipedia: refers to early European exploration ↩︎

- Vicki Robertson, 2024. Exploring Cossack in Western Australia: A Historic Hidden Gem. Retrieved 10 Dec 2025 from https://theinsightfulodyssey.com/exploring-the-cossack-old-town-in-western-australia-a-historic-gem/ ↩︎

- Karratha is Calling, n.d. Explore Cossack. Retrieved 10 Dec 2025 from https://www.karrathaiscalling.com.au/explore/cossack/ ↩︎

- Aussie Towns: refers to earlier names for port ↩︎

- Clayton Roberts, 1999. Cossack: Ghost town of the north-west. Published in Minifest, Vol 2, No 1, p28. Retrieved 1 Dec 2025 from https://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/ManifestJlAUCS/1999/12.pdf ↩︎

- WA Now and Then: refers to port and pearling ↩︎

- Karratha is Calling: refers to port and pearling ↩︎

- Aussie Towns: refers to pearling ↩︎

- ibid: refers to pearling luggers ↩︎

- Wikipedia: refers to pearling luggers ↩︎

- Wikipedia: refers to use of women and children for pearling work ↩︎

- Kopp, p5: refers to the use of aboriginal people for pearling work ↩︎

- TPG, p12: refers to the use of local aboriginal people for pearling work ↩︎

- ibid: refers to death due to inflammation of the lungs ↩︎

- Michael J. McCarthy, 2002. Iron and Steamship Archaeology: Success and Failure on the SS Xantho. p.37. Fremantle, WA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ↩︎

- Ross Anderson, 2013. First port in the Northwest A maritime archaeological survey of Cossack 25-30 June 2012. Western Asutralia: Report–Department of Maritime Archaeology, Western Australian Museum– No. 297. p.22. Retrieved 10 Dec 2025 from https://museum.wa.gov.au/maritime-archaeology-db/sites/default/files/no._297_cossack_ma_survey_2012.pdf ↩︎

- Wikipedia: refers to ethnic segregation ↩︎

- TPG, p.72, 81: refers to evidence of multicultural society ↩︎

- Wikipedia: refers to ethnic diversity ↩︎

- WA Now and Then: refers to Chinese, Japanese, Singhalese and Turkish service businesses ↩︎

- Roberts, p.28: refers to many ethnic groups and the services provided ↩︎

- Aussie Towns: refers to Chinese market gardens and an Afghan Transit Camp ↩︎

- Kopp, p.10: refers to Chinese market garden and difficulty experienced by Europeans ↩︎

- State Library of Western Australia, N.D. 20990PD: Government buildings, Cossack, Western Australia, 1894. 2 photographs : black and white ; 11 x 16 cm from a collection of photographs of Cossack and residents; 6005B/7, 10; retrieved 11 Dec 2025 from https://encore.slwa.wa.gov.au/iii/encore/record/C__Rb4745102 ↩︎

- Karratha is Calling: refers to the Pilbara gold rush 1887 ↩︎

- TPG, p.12: refers to the importance of the port as a staging place for prospectors ↩︎

- ibid p.15: refers to the construction of buildings in the town ↩︎

- Wikipedia: refers to the heritage buildings remaining in Cossack ↩︎

- State Library of Western Australia, n.d. 4014B: Cyclone damage at Cossack Wharf, with the schooner Harriet and streamship Beagle washed ashore, 1898. Photograph : black and white. Retrieved 11 Dec 1025 from https://encore.slwa.wa.gov.au/iii/encore/# Note: title taken from caption on the back of the photograph. ↩︎

- Wikipedia: refers to the causeway noting it remains the only access to the town from the land. ↩︎

- Wiki Australia, n.d. Cossack: Western Australia, Australia. Retrieved 12 Dec 2025 from https://wikiaustralia.com/destination/cossack/ ↩︎

- Aussie Towns: refers to silting in the harbour ↩︎

- Wikiwand, n.d. Cossack: Decline of the township. Retrieved 12 Dec 2025 from https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Cossack,_Western_Australia ↩︎

- Kopp, p.25: refers to cyclones and unsuitability of port for larger vessels ↩︎

- Wiki Australia: refers to move of pearling industry to Broome ↩︎

- TPG, p.15: refers to unsuitability of port for larger vessels and move to Broome ↩︎

- Wikiwand: refers to depletion of pearling grounds ↩︎

- TPG, p.15: refers to attempts to revive the town ↩︎

- WA Now and Then: refers to lazarette and turtle soup ↩︎

- inHerit. Cossack Lazarette. http://inherit.stateheritage.wa.gov.au/Public/Inventory/Details/6f71b8fa-05b3-49b8-8149-ae5045b50868. Retrieved 17 Sep 2023 ↩︎

- Wikipedia: refers to the leprosarium ↩︎

- TPG, p.15-16: refers to various attempts to revive the town ↩︎

- TPG, p.34-35: refers to restoration and classification of heritage buildings ↩︎

- Trails WA, n.d. Cossack Heritage Walk Trail. Retrieved 12 Dec 2025 from https://trailswa.com.au/trails/trail/cossack-heritage-trail ↩︎

- Robertson, 2024: refers to the Cossack heritage trail ↩︎

- TPG, p.16: refers to Heritage listing and tourism ↩︎

- Dietsch, 2024: refers to the closure of the tourism precinct ↩︎

Further research

- Stevenson, Kinder & Scott photograph collection

- Horton, David R. (1996). “Map of Indigenous Australia”. AIATSIS. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- Ross Anderson; Jeremy Green (2011). Anketell Port Development – Maritime and Underwater Cultural Heritage (MUCH) desktop analysis (PDF). Department of Maritime Archaeology, Western Australian Museum. p. 2-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 July 2022.

- “Cossack Draft Master Plan – Concept Stage” (PDF). A joint project between the Department of Housing and Works, the Shire of Roebourne and the Heritage Council of WA. November 2006. Archived from the original (pdf) on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- “Cossack Historic Facts” (PDF). Shire of Roebourne. Archived from the original (pdf) on 3 September 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- “FROM THE PAST”. The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1950). Perth, WA: National Library of Australia. 4 April 1914. p. 11 Edition: Third edition. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- Murphy, Rosemary (11 August 2024). “Push to bring life back into historic Pilbara town after years of broken promises”. ABC News. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- Rollo, Lindsay (2025). Iron Road: The Story of the Roebourne-Cossack-Point Samson Tramway. Perth: Independently published. ISBN 9780995393936.

- FHWA, 2023. Our Pilot Communities. Retrieved 15 Dec 2025.

- Sam Wilson, n.d. The H.M. Wilson Archives: Cossack. Retrieved 15 Dec 2025 from https://hmwilson.archives.org.au/tags/cossack