Demographics

Region: Wheatbelt

LGA: Dalwallinu

Industry: Agriculture

Other Names: Miamoon, Mia-moon, Gnookadunging

Open Street Map: -30.063900774121873, 116.48060333979153

What3Words: ///makeover.melts.edgily

Settled: 1909

Gazetted: N/A

Current status: Now a nature reserve

Abstract

The history of Mia Moon (or Miamoon), a remote locality situated 17 kilometres west of Wubin in the Shire of Dalwallinu, is an exemplar of Western Australia’s boom-and-bust agricultural settlement pattern.1 The earliest factor influencing life here was the natural environment, specifically the large granite outcrop and the reliable gnamma hole (Gnookadunging), which served as a critical water source for Aboriginal custodians and early European explorers like John Forrest in 1869. The region’s economic growth was fueled by the early 20th-century agricultural boom, characterized by land selection in the Nugadong area starting around 1908, focused on wheat and sheep farming. This growth fostered a brief period of social cohesion, centered around the Mia Moon School (originally West Wubin school) and its sporting clubs (1920s–1940s). However, economic hardship, isolation, and eventually school closure (1950) led to demographic contraction. Today, Mia Moon’s significance has transitioned from a farming hub to a sparsely populated region (17 people recorded in 2021) to an environmental sanctuary and nature reserve renowned for its spectacular wildflower displays, particularly orchids.

History

Mia Moon, or Miamoon as it is frequently known, is a locality that whispers of a forgotten past. Located 17 kilometres west of the township of Wubin and 27 kilometres from Dalwallinu, its evocative name suggests a beautiful synthesis of cultures, possibly derived from the Aboriginal word mia, meaning ‘home,’ rendering the name as the “home of the moon” – a fitting moniker for a location often defined by its granite-studded wilderness. Today, Mia Moon is recognized primarily as a nature reserve, a small pocket of biodiversity and a popular spot for viewing wildflowers. Yet, its designation as a locality signifies a profound history of human endeavour, dictated by harsh environmental realities and shaped by the ambition of pioneers.2 3 4

The Environmental Foundation and Aboriginal Heritage

The most enduring environmental feature of the Mia Moon landscape, and arguably the single most important factor enabling its initial human settlement, is the distinctive granite outcrop. Within this hard rock formation lies a natural cavity known as a gnamma hole. These cavities function as vital, natural water tanks, replenished by underground stores and rainwater run-off.5

For untold generations, this water source was fundamental to the survival of Aboriginal people traversing the region. Historical records indicate that the explorer John Forrest noted this specific water source when he journeyed through the area in 1869, referring to it at the time by the Aboriginal name “Gnookadunging”. The reliable presence of water, captured and stored naturally by the granite, determined Mia Moon’s enduring importance as a focal point for movement and, eventually, permanent settlement.6

The Economic Surge: Pioneering and Agriculture

The growth phase of the Mia Moon locality coincided directly with the state government’s push into the Wheatbelt during the early 20th century. The areas encompassing Mia Moon, Wubin, and Jibberding were surveyed and opened for selection starting around 1907 and 1908. This era was marked by the arduous economic toil of pioneers arriving to clear the virgin scrub and establish farms dedicated primarily to wheat and sheep.7

Pioneers such as the Arthur, Klein, and Ellison families took up land holdings in the Nugadong Agricultural Area, with grants issued as early as January 1908. Early settlers, who included figures like Jim Ellison, who took up Nugadong Lot No. 17 in July 19088, arrived with the mandate to carve profitable agricultural holdings from virgin bush. These early years were defined by immense hardship. Farmers endured unremitting hard toil on the land, and women often faced isolated, lonely lives. Early housing, as documented by pioneering women like Elizabeth Klein9, consisted of primitive structures like tents, and later, white-washed hessian huts, which offered little respite from the extremes of hot summers and cold winters. The perennial struggle for water remained an economic barrier; Wilhelm Klein had to organize the sinking of a well in 1908, which proved only sufficient for stock, meaning drinking water had to be carted from an Aboriginal soak two miles distant, or even eighteen miles away from Meelya Well, as was the case for the Arthur family.10

The economic and demographic vitality of the area led to the expansion of supporting infrastructure and services in the vicinity of Wubin, which acted as the main regional hub.11 However, this period of development was not without its darker elements; records note that local storekeeper Harold Eaton Smith was tragically murdered at Miamoon in 1928.12 Despite these challenges, farming interests consolidated, exemplified by purchases such as Major R.D.C. Blake acquiring a Miamoon property in partnership with Jim Harris in 1946.13 Gus Liebe, a prominent Perth builder who became a large landholder at Wubin, brought an industrial scale to farming, once purchasing ten tractors at once. The extension of the government railway line through Wubin in 1915 solidified the area’s economic function as a transport hub for grain. Local enterprise thrived briefly, evidenced by businessmen like Tom Corteen, who acquired the “Mt Hawke” farm for his son in the area in 192814, and Ralph Harris, who purchased his property, “Iunstun” (meaning iron stone), just west of Wubin in 1926.15

Social Growth and Contraction = The Rise and Fall of the School

The social and cultural focus of the early Mia Moon community was undoubtedly the Mia Moon School, serving the children of West Wubin, Nugadong, and surrounding farms. Educational access was difficult; in the 1920s, children traveled long distances, sometimes 10 miles, often via horse and cart. This necessity drove the community to establish and relocate educational facilities.

The school building itself, indicative of the transient nature of small rural settlements, had a notable history of migration. It originated as the Dalwallinu school, was moved to Jibberding in 1921, relocated to West Wubin in 1925, and officially renamed Mia Moon School in 1930.16 It was moved yet again in 1935, eight kilometres further west to Nugadong, following petitions from parents like Ernest Brown who noted his children had to get up at 5 am to travel to the old site.17 Teachers, such as Florence Bell (1925–29), Eileen Chambers (1932–34), and Gertrude Thompson (1937–40), lived locally, often boarding with families like the Sanders.18

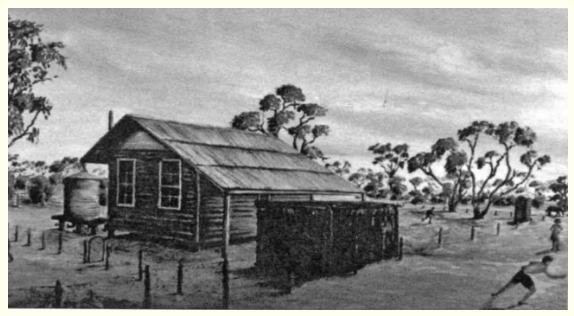

“Miamoon Bush School”

A copy of a painting by Marjorie Counsel and owned by former Miamoon Pupil, Bill East, who donated it to the Wubin Community.19

This school served as the nucleus of social life. Near the school grounds were the Miamoon tennis courts, and the locality fielded its own cricket teams. However, the structures reflected the rudimentary nature of the community; Dorothea Lock, teacher from 1935–37, wrote scathingly to the education department about the cheerless and uncomfortable school building, noting rain streaming through roof holes, cracks in the weatherboards, and a stove so dangerous she refused responsibility for lighting it.20

The early 1930s marked the onset of economic decline, exacerbated by the Great Depression. Farmers like Arthur Counsel suffered, losing their land. By 1932-33, the local Wubin-Buntine Tennis Association saw competitive play involving teams from Miamoon. Yet, the overall population was contracting.

The decisive sign of the locality’s terminal decline arrived when the Mia Moon School, which had provided education for generations of children, closed in 1950. In a practical, bureaucratic gesture that symbolized the end of the settlement, the physical school building itself was removed for re-erection in Latham, a process for which tenders were invited in January 1952.21

Modernity and Preservation

In the modern era, Miamoon has witnessed a dramatic contraction in its permanent population, transitioning from a thriving pioneering community to a state of near-solitude. The locality is defined by its minimal remaining population, with the 2016 Census recording only 15 people22, rising slightly to 17 people in 202123. This small resident base occupies only eight private dwellings. While the 2021 census data indicates a high median weekly household income of $5,500 (compared to $2,250 in 2016), the Australian Bureau of Statistics notes that these median values “may be affected by confidentiality in small areas”, reflecting the consolidation of agricultural land into larger, capital-intensive holdings. While this low population makes statistical analysis difficult, the census recorded a surprisingly high median weekly household income of $5,500, suggesting that the remaining inhabitants are associated with large, consolidated and commercially successful agricultural holdings, or that the small sample size has produced a statistical anomaly.

Economically, Mia Moon has transitioned. The physical remnants of the past – a strip of concrete universally known as the ‘cricket pitch’ and the old school site – are now tourist attractions alongside its natural assets.

Environmentally, Mia Moon is celebrated as a small reserve that functions as an important sanctuary for local flora. The reserve is covered in wildflowers, particularly during the July to October season, noted for an array of orchids, including pink candy, blue fairy, spider, and sun orchids, along with drifts of white and yellow pom pom everlastings. It is this enduring natural spectacle that ensures Mia Moon, though socially and economically diminished from its pioneering zenith, remains a place worth visiting.

Timeline

- 1869: Explorer John Forrest notes the crucial granite water source, referring to it by the Aboriginal name “Gnookadunging”.

- 1907-1908: Land in the area, including the Nugadong Agricultural Area, is surveyed and opened for selection; the first pioneers begin to take up holdings.

- 1925: The school serving the locality, having originated in Dalwallinu and moved to Jibberding in 1921, is relocated and established as the West Wubin School.

- 1928: The local storekeeper and farmer Harold Eaton Smith is murdered at Miamoon.

- 1930: The West Wubin School is officially renamed Mia Moon School.

- 1932-1933: Miamoon participates in local sporting competitions, fielding teams in the Wubin-Buntine Tennis Association.

- 1935: The Mia Moon School building is moved for a third time to Nugadong Location 1 (approximately 8 km further west).

- 1937: Gertrude Thompson, later Gertrude Skipworth, begins her tenure as Head Teacher at Mia Moon School, serving until 1940.

- 1946: Major R.D.C. Blake and Jim Harris purchase a property at Miamoon.

- 1950: The Mia Moon School closes.

- January 1952: Tenders are sought for the removal and re-erection of the former Mia Moon School building at Latham.

- 2016: Census records the population of Miamoon as 15 people.

- April 2017: The Mia Moon Reserve is highlighted for its significant wildflower biodiversity, especially its range of orchids, solidifying its modern identity as an environmental sanctuary.

- 2021: The population of Miamoon is recorded as 17 people, inhabiting 8 private dwellings.

Map

Sources

- WA Now and Then, n.d. Miamoon Near Wubin. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://www.wanowandthen.com/Miamoon.html ↩︎

- NACC, n.d. Parks for People – Mia Moon, Shire of Dalwallinu. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://www.nacc.com.au/parksforpeople-mia-moon-shire-dalwallinu/ ↩︎

- WA Now and Then, 2022. Miamoon – Western Australia. Video retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://youtu.be/cyitg4dOy78?si=q4HaPsowQdiSDCzM ↩︎

- Bert Cail, Judith Reudavey, Joy Wornes, 2005. Prepared to Pioneer: A History of Wubin 1908-1939. p.2. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://garrygillard.net/wubin/wubin.pdf ↩︎

- NACC: refers to granite outcrops and gnamma holes ↩︎

- Shire of Dalwallinu, n.d. Places of Interest: Mia Moon. Retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from https://www.dalwallinu.wa.gov.au/council/about-dalwallinu/places-of-interest/mia-moon.aspx ↩︎

- Cail et al: p.1 ↩︎

- ibid, p.36 ↩︎

- ibid, p.3 ↩︎

- ibid, p.3-106 (provides profiles of life in the area in the early days) ↩︎

- ibid, p.1 ↩︎

- ibid, p.88. ↩︎

- ibid, p.10 ↩︎

- ibid, p.27 ↩︎

- ibid, p.44 ↩︎

- ibid, p.120 ↩︎

- ibid, p.12 ↩︎

- Carnamah Historical Society & Museum, n.d. WA State School Teachers 1900-1980: Mia Moon. Retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from https://www.carnamah.com.au/teachers?keyword=mia+moon ↩︎

- Cail et al: p.119 ↩︎

- ibid, p.60 ↩︎

- Government Gazette, 1952. Vol.9 Perth: Friday, 25th January, 1952. p.174 retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from ↩︎

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016. 2016 Census all persons QuickStats. Retrieved 5 Dec f2025 from https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2016/SSC50933 ↩︎

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2021. 2021 Census all persons QuickStats. Retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/SAL50943 ↩︎

- Satellite image of Mia Moon Reserve retrieved 5 Dec 2025 from https://www.legislation.wa.gov.au/legislation/prod/gazettestore.nsf/FileURL/gg1952_009.pdf/$FILE/Gg1952_009.pdf?OpenElement https://what3words.com/makeover.melts.edgily ↩︎