The Saltbush Siding and the Lime Empire

Australia for Everyone1

Demographics

Region: Goldfields-Esperance

LGA: Kalgoorlie-Boulder

Industry:Railway, Limestone

Other Names: Naretha Railway Siding, 205 Mile Camp

Meaning: Saltbush

Open Street Map: -30.557019946570758, 124.87405201947526

What3Words: ///expecting.unstuck.techy

Settled: 1912

Gazetted: N/A

Abandoned: About 1966

Abstract

Naretha, located deep within the arid Nullarbor Plain in Western Australia, stands as a poignant historical marker of the Trans-Australian Railway (TAR) and the isolated communities that sustained it. Originating as the ‘205 mile’ construction camp, Naretha’s existence was intrinsically tied to the economic necessity of the railway, serving initially as a ballast crushing site and later gaining prominence as the site of the Kiesey Brothers’ Lime Kilns from the 1930s until 1965. Its social fabric was characterized by profound isolation, harsh, improvised living conditions, and dependence on imported water and the vital “Tea and Sugar Train.” The environmental challenge of extreme aridity defined its early growth and subsequent decline, which accelerated with the shift from steam to diesel locomotives in the 1960s. Today, Naretha (Aboriginal name for Saltbush) survives solely as a remote railway siding, a ghost of its vibrant past.

History

The history of Naretha is inextricably linked to the ambition of Federation to connect the disparate Australian colonies with a transcontinental railway. The successful completion of the Trans-Australian Railway (TAR) in 1917 necessitated the creation of numerous small settlements across the vast and arid Nullarbor Plain to house the men – known variously as railway men or fettlers – who maintained the line. Naretha, situated 1,358.5 kilometres from Port Augusta and roughly 360 kilometres east of Kalgoorlie, was established as one such locality, initially identified as the ‘205 mile’ camp. The name Naretha itself is the local Aboriginal term for Saltbush.2 3 4

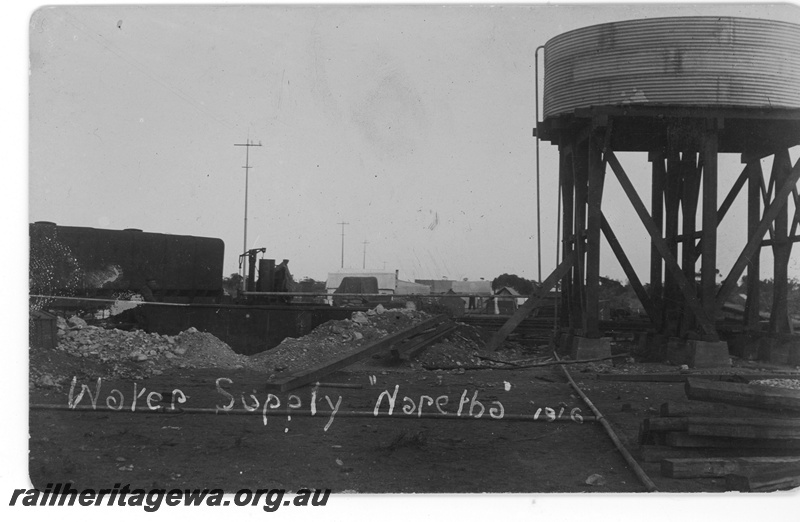

Rail Heritage WA5

The early raison d’être for Naretha was purely economic and practical. The settlement was developed to support the physical requirements of the railway line, featuring rock piles and a crushing plant used for the creation of railway line ballast. The importance of Naretha during this foundational period is reflected in early military records; Private Charles Robert Thomas, who enlisted in World War I in 1916, listed Naretha, Trans Line via Kalgoorlie, as his address.6 Moreover, it was here, in 1916, that Reverend Joseph Budge built the modest St Lukes Anglican Church, which functioned as both a church and a meeting hall for the transient workers.7 8

SLWA9

Economic Growth: The Era of Lime and Rail Services

Naretha’s most significant period of sustained economic activity arrived not solely from the government railway works but from the development of a crucial industrial mineral: lime. In 1930–31, Charles and George Kiesey discovered commercially viable surface limestone a few miles west of the Naretha siding. Recognizing the proximity to both the rail line and a necessary belt of timber required for fuel, the brothers established the Lime Kilns, sometimes referred to as Lime Siding or the 913-Mile.10

The economic fortunes of the lime operation were tied directly to the gold mining industry in Kalgoorlie, where lime serves as a necessary component of the gold extraction process. Until December 1965, the Kiesey Brothers supplied the Eastern Goldfields gold mines with a reliable average of 500–700 bags of lime weekly. Furthermore, the railways themselves provided a market, utilizing Naretha’s lime in the water purifying plant located at Rawlinna to treat the mineralised underground water vital for steam trains. The Kiesey Brothers’ operation was notable for its use of traditional methods and equipment, requiring highly skilled and dedicated labour for the selection and careful layering of stone and fuel in the kilns.11

In addition to the lime production, Naretha continued to serve the broader Trans-Australian line. In the 1950s, demonstrating Naretha’s relative stability during the post-war era, a bakery was constructed to provide freshly baked bread for the passenger trains and the workers along the route.12 13 14

Social and Environmental Constraints on the Nullarbor

Life in Naretha was profoundly shaped by the arid environment of the Nullarbor Plain, classified by international standards as arid or semi-arid. The environment presented immense social and logistical hurdles, particularly concerning water. Crucially, there was no reliable local water supply for the settlement. Water had to be purchased in Kalgoorlie, hauled to the siding by train, off-loaded, and then trucked to individual households, where it was stored in 44-gallon drums. Rainwater was carefully collected from roof catchment areas, and water for domestic needs was supplied from dedicated water wagons attached to the weekly train arriving from Port Augusta.15 16 17

The reliance on imported resources fostered a unique, resilient social environment. The rail line was the umbilical cord sustaining these isolated communities. For decades, essential supplies were provided by the weekly “Tea and Sugar Train,” which supplied provisions, including banking and postal facilities, to residents like the railway men, fettlers, and those scraping a living around the line.18 19

The workforce and their families represented a microcosm of Australia’s post-Federation immigration waves. While the Kiesey brothers were German-born, the workforce included Yugoslav, Italian, English, Australian, Irish, and Dutch individuals, although later the majority were Yugoslav. The Croatian immigrant Marko Andrijich20, who arrived in 1936, resided in Naretha for two years with his wife Vica and daughter Marija before moving to the Swan Valley. The domestic life was characterized by primitive conditions and improvisation, especially during the Depression years. Early homes had walls made of filter cloth or hessian bags, sparse furniture, and dirt floors covered with a lime residue mixture.21

An environmental curiosity tied to the locality is the Naretha bluebonnet (Northiella narethae), a species of parrot endemic to this arid Nullarbor region and named after the siding where the type specimen was first collected in the late 1910s. The parrot’s existence and protection were noted in Department of Mines files as late as 1979.22

Decline and Modern Existence

Naretha’s decline was precipitated by two major shifts that impacted its economic viability.

- First, the lime industry ceased operations in December 1965, ending the primary economic driver outside of railway maintenance. This closure removed a significant employer and consumer market from the area.23 24

- Second, technological advancements in the railway sector fundamentally changed the logistical necessities of the Trans-Australian line. The adoption of diesel locomotives in the 1960s eliminated the requirement for frequent watering stops necessary for steam engines. Furthermore, rapid advances in railway engineering, particularly the introduction of highly durable concrete sleepers, reduced the need for the small, isolated, locally based maintenance gangs. Consequently, railway staff dwindled, settlements were progressively closed down, and families were resettled elsewhere. The specialized supply lifeline, the Tea and Sugar Train, ceased its colourful run on August 30, 1996.25

Though the buildings and community infrastructure vanished – including the St. Lukes Church which was relocated to Westonia in 1918, and the school which was removed around 1944 – Naretha retains its existence as a functional railway locality. Today, it consists only of a loop and siding. It serves as a drop-off point for mail to nearby stations and is occupied by the residents of an old Commonwealth Railways guards van. Naretha remains a vital location on the rail network, evidenced by the extensive emergency and repair works undertaken by the Australian Rail Track Corporation (ARTC) following a major freight train derailment of 39 wagons between Rawlinna and Naretha in December 2015.26 27 28

The story of Naretha, nestled deep in the Nullarbor, mirrors that of many remote Australian settlements built entirely on logistical necessity. Its growth was driven by the economic synergy between the railway and the Kalgoorlie goldfields, while its decline was the inevitable consequence of environmental harshness compounded by technological obsolescence. It persists, however, as a resilient node in the enduring infrastructure connecting the east and west of the continent.

Timeline

- Present Day: Naretha remains a railway station/siding, a regular drop-off point for mail, and home to the occupants of an old Commonwealth Railways guards van.

- Pre-1916 (Aboriginal History): The area is known traditionally as Naretha, meaning Saltbush.

- Late 1910s: Naretha is established as the ‘205 mile’ camp (a distance from Kalgoorlie) along the newly constructed Trans-Australian Railway.

- 1916: Private Charles Robert Thomas enlists in WWI, giving Naretha as his address.

- 1916: St Lukes Anglican Church (also used as a meeting hall) is built by Reverend Joseph Budge at Naretha.

- Late 1910s: A field worker observes a Naretha parrot (later named the Naretha bluebonnet, Northiella narethae) caught at the settlement, leading to the species’ formal description in 1921.

- October 1918: St Lukes Church is dismantled and moved from Naretha to Westonia due to the disbanding of the railway camps.

- 1930–1931: Charles and George Kiesey discover surface limestone near the siding and establish the Lime Kilns operation.

- March 1933: Jean Strika (later Zuvela) arrives to work as a housekeeper/cook at the Lime Kilns settlement.

- 1936–1938 (Approx.): Marko Andrijich, a Croatian immigrant, resides in Naretha for two years with his family.

- 1939–1944: Stanley Jones is recorded as the Head Teacher at the Naretha School.

- 1944 (Approx.): The Naretha School is mentioned in records related to its removal.

- 1950s: A bakery is built at Naretha to supply freshly baked bread to the passenger trains and rail workers.

- 1950s–1960s: The railway begins transitioning from steam to diesel, lessening Naretha’s importance as a watering stop.

- December 1965: The Kiesey Brothers Lime Kilns operation, which supplied lime for the Kalgoorlie goldfields, ceases operations.

- 1966: Exploitation of the Nullarbor Limestone near Naretha ends.

- 1980s: Technological advancements and the use of modern materials (like concrete sleepers) lead to the progressive winding down of maintenance staff and settlements along the line.

- August 1996: The “Tea and Sugar Train,” which supplied isolated communities like Naretha, makes its final run.

- 2015 (December): A major freight train derailment involving 39 wagons occurs between Rawlinna and Naretha, requiring extensive recovery and repair work by the Australian Rail Track Corporation.

Map

satellites.pro29

Sources

- Australia for Everyone, n.d. Naretha. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://www.australiaforeveryone.com.au/files/images/naretha-siding.jpg ↩︎

- Wikipedia, 2025. Localities on the Trans-Australian Railway. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Localities_on_the_Trans-Australian_Railway#/media/File:Trans-Australian_Railway_map_provided_to_passengers_circa_1960.png ↩︎

- Australia for Everyone, n.d. Ghost Towns and Sidings of the Nullarbor Plain. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://www.australiaforeveryone.com.au/files/ghost-towns-nullarbor.html ↩︎

- Let’s Go Travelling, n.d. Railway Ghost Towns and Sidings on the Nullabor Plain. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://pocketoz.com.au/rail/ghost-towns-nullarbor.html ↩︎

- Rail Heritage WA, n.d. P16795 Water tower with a cylindrical corrugated iron tank, Naretha. Commonwealth Railways. Photo, B&W, retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://www.railheritagewa.org.au/archive_scans/displayimage.php?album=search&cat=0&pid=24404#top_display_media ↩︎

- Collections WA, n.d. Australian Army Museum of Western Australia: World War I, Europe, THOMAS, 32 Battalion, 1916. Studio Portrait in B&W retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://collectionswa.net.au/items/ae341af6-dafa-4d52-9b0f-66d3556bf2ca#block-storydata-theme-branding ↩︎

- Heritage Council of Western Australia, 2022. St Lukes Anglican Church. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://inherit.dplh.wa.gov.au/public/inventory/details/03ff1f11-598e-47f5-abce-8b15ca529be8 ↩︎

- Shire of Westonia, n.d. Now & Beyond: St Lukes Anglican Church. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://www.westonia.wa.gov.au/explore/about-westonia/now-beyond.aspx ↩︎

- State Library of Western Australia, n.d. Rock piles and crushing plant, 1917. Photograph, b&w, retrieved 4 Dec f2025 from https://encore.slwa.wa.gov.au/iii/encore/record/C__Rb2502119 ↩︎

- King, Norma, 2019. Goldfield Stories of Western Australia: The Lady at the Lime Kilns (Part 1). Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://www.goldfieldstories.com/2019/03/the-lady-at-lime-kilns-part-1.html?m=0 ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Australia for Everyone: refers to the Bakery at Naretha ↩︎

- Let’s Go Travelling: refers to the Bakery at Naretha ↩︎

- Adventures, n.d. Western Australian Siding of the Trans Australian Railway. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://www.adventures.net.au/information/sidings-of-the-trans-line ↩︎

- Dept of Mines, 1980. Mineral Resources of Western Australia. p.10. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://library.dbca.wa.gov.au/FullTextFiles/007648.pdf ↩︎

- King, 2019: refers to water supply ↩︎

- Australia for Everyone: refers to water scarcity ↩︎

- Wikipedia, Localities ..: refers to the railway as sustaining isolated communities ↩︎

- Let’s Go Travelling: refers to the Tea & Sugar Train ↩︎

- Western Australian Museum, n.d. Welcome Walls: ANDRIJICH, Marko. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://museum.wa.gov.au/welcomewalls/names/andrijich-marko ↩︎

- King, 2019: refers to immigrant labour and primitive living conditions ↩︎

- Wikipedia, 2025. Naretha bluebonnet. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naretha_bluebonnet ↩︎

- Dept of Mines, 1980: p.75 ↩︎

- King, 2019: refers to closure of lime kilns ↩︎

- Australia for everyone: refers to the changing technology and closure of services ↩︎

- Heritage Council, 2022: refers to relocation of church ↩︎

- State Records Office, 1944. Haig School ( Trans Railway ) Erection Removal of Naretha School. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://archive.sro.wa.gov.au/index.php/haig-school-trans-railway-erection-removal-of-naretha-school-1944-1315 ↩︎

- Australia for everyone: refers to present day Naretha ↩︎

- Satellites.pro, 2025. Naretha. Retrieved 4 Dec 2025 from https://satellites.pro/Naretha_map ↩︎

Further research

- Australian Army Survey Corps. (1942). Map of Naretha, Western Australia retrieved December 4, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-233277720 prepared as part of Australia’s defence strategy during WWII