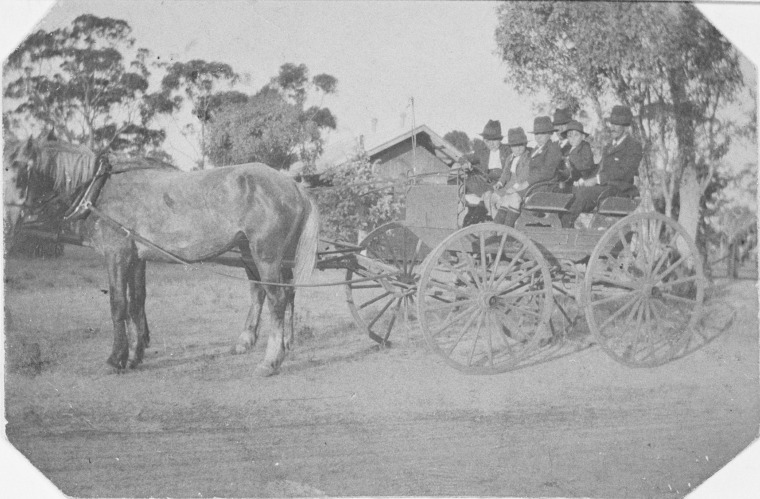

State Library of WA 1

Demographics

Region: Wheatbelt

LGA: Narrogin

Industry: Agriculture

Other Names: Nomans Lake

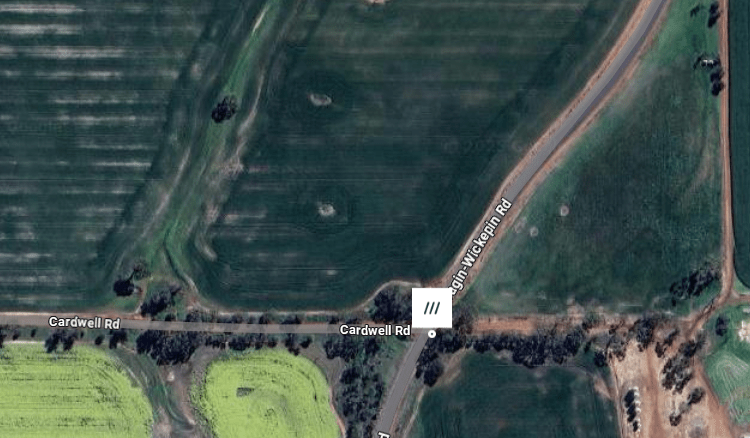

Open Street Map: -32.92171350894379, 117.48022983826978

What3Words: ///whisk.hazily.capillary

Settled: 1890s

Gazetted: 1915

School closure: 1938

Abstract

The history of Noman’s Lake (also known as Nomans Lake) traces the trajectory of many pioneering settlements carved out of the Western Australian wheatbelt in the early 20th century, characterized by rapid growth followed by gradual decline. Located within the Narrogin Shire, the area was opened for settlement following the Goldrush migration, attracting settlers, largely from the Eastern States, who sought farming land. The community’s establishment was defined by crucial social infrastructure, including the Noman’s Lake School (opened 1910, closed 1938) and the Agricultural Hall (constructed from 1912). These facilities fostered a robust social and sporting life, supported by the Yilliminning-Kondinin Railway siding and a local store. However, economic volatility and environmental factors, notably rising soil salinity, contributed to its decline. Today, while the population is small (50 residents in 2016), the area remains an active agricultural locality, distinguished by the enduring utility of the Nomans Lake Hall and new efforts toward ecological restoration.

History

The Foundations of the Settlement

The history of Noman’s Lake, a locality within the Narrogin Shire of the Wheatbelt region, is inextricably linked to the vast demographic shift Western Australia experienced at the turn of the 20th century. The initial allure of the goldfields brought a massive influx of people—the population nearly quadrupled between 1891 and 1901—and as the gold fever subsided, many newcomers, predominantly from the Eastern States, turned their ambition toward the agrarian frontier. This demand compelled the Land and Surveys Department to initiate the large-scale survey of farming blocks.2 3 4

Although evidence suggests sandalwood cutters and shepherds traversed the general area prior to formal settlement, and explorers such as John Forrest (1871) and Surveyor Oxley (1890s) noted the locale, the official push for agricultural habitation commenced with the surveying of farm blocks between 1904 and 1907. Prospective farmers often “selected” their land even before the surveys were finalized.5

The physical geography of the district provided both opportunity and challenge. Noman’s Lake is one of a chain of water bodies forming part of the headwaters of the Arthur River, including Toolibin Lake and Little White Lake. In the days of early settlement, these water bodies were described as fresh, serving as popular spots for social activities like swimming, boating, picnics, and even fishing.6 7

The Rise of a Community Hub (1907–1920s)

The first concerted efforts to establish a civic presence came from the pioneering families themselves. Records indicate that as early as June 2, 1907, Mr. E. Cardwell issued an impassioned plea to the Education Department for a school service. By March 1908, Mr. C. Cardwell, acting on behalf of the East Narrogin Progress Association, submitted a formal application for a school.

After delays, including difficulty securing a dedicated school site, the application for a Provisional School was finally made in late 1909. The Noman’s Lake School officially opened its doors on November 1, 1910, after the contract builder, Mr. H. Marsh, completed the transportable tent school and quarters, despite setbacks due to wet weather and impassable roads. The school site itself was a significant historic and social place for early settlers.8

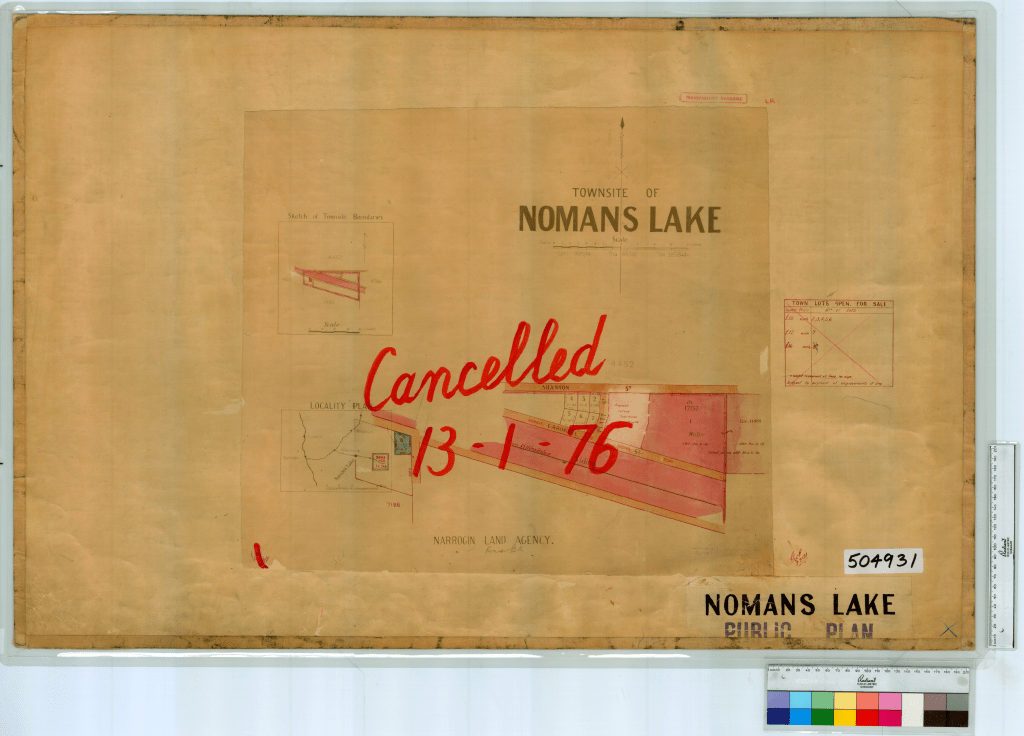

State Records Office of WA9

Concurrent with the establishment of the school was the construction of the Noman’s Lake Agricultural Hall (later known as Nomans Lake Hall). The Lakes Progress Association requested financial assistance for materials in June 1909, with settlers guaranteeing the provision of voluntary labour for carting materials and construction. Built by Bonney & Sons of Narrogin, the Hall was opened by Mr. E.B. Johnston M.L.A. on December 11, 1912. Financed through local fundraising, a government subsidy, and a small debt, the Hall quickly cemented its status as the social heart of the district. It served multiple purposes: a venue for numerous community activities, including music lessons, gymnastic classes, Church services, and meetings for groups such as the CWA and the Farmers and Settlers Association.10

The robust social calendar was reflected in events like the children’s entertainment and prize distribution marking the end of the 1913 school term. This event, held on Boxing night in the Agricultural Hall after being postponed from December 19th due to a flood or “deluge,” featured dialogues given excellently by the children, distribution of books by Mr. A. Plant, J.P., and dances—including separate sets for parents and children who were “carefully partner-ed”. This festive spirit was later enhanced by the installation of a Wizard light in the early 1920s, fuelled by Shellite.11 12

Economic Drivers and Social Fabric

The economic viability of Noman’s Lake was fundamentally linked to the expansion of the Western Australian Government Railways. The townsite was formally gazetted on September 24, 1915, following the construction of the Yilliminning – Kondinin Railway.

The establishment of the Noman’s Lake Siding provided the necessary infrastructure for agricultural production, later supported by a Cooperative Bulk Handling (CBH) Bin. This economic node led to commercial development; Mr. and Mrs. Charlie Barnes built a store with a Post Office near the siding around 1913, which also served as accommodation for railway gangers and their families.13

The community’s social fabric was deeply woven with competitive sports. The decade of the 1920s saw the formalization of local clubs. A cricket team participated in the Harrismith and Districts Cricket Association, playing teams like Toolibin. Though the Noman’s Lake team faced challenges, including being short of their full strength and having no practice in a 1927 match against Toolibin, they were described as determined. A football team, “The Lakes,” was formed around 1928, displaying blue and white V colours while competing in the Harrismith and Wickepin Associations. Even the local tennis club was active, though perhaps less successful; known as the “Renown Tennis Club,” it was made up partly of “cast off cricketers of last year” and was deemed “100 per cent. worse than their brother sports”.14 15

The Environmental and Economic Toll

Despite the energy and resourcefulness of the settlers, the life of the pioneering farmer was harsh, particularly in the Wheatbelt. Historical records highlight persistent financial distress, reflecting the economic volatility of the era. State Records office archives list civil writs and bankruptcy filings against several Nomans Lake farmers in the mid-1920s and early 1930s, including Sydney Alfred Lee (1925), William Joseph Lee (1928), and E. E. Hennig (1932). This era of struggle coincided with the environmental consequences of widespread land clearing for agriculture.16

The ecological shifts proved devastating. Clearing bush caused the water table to rise, mobilizing billions of tonnes of salt stored in the subsoil and dissolving it, leading to increased soil salinity. This ecological change fundamentally altered the landscape: the lakes, once fresh and utilized for recreation, became “quite salty”. The sources visually testify to this environmental toll, showing expanses of dead trees in the saline lake beds.

The community’s decline followed these environmental and economic pressures. The Noman’s Lake School, which served the community for almost 28 years, ceased operations on March 14, 1938, due to a “diminished enrolment of pupils”. The local store and Post Office agency, passed through several hands, was eventually destroyed by fire when a hay shed adjoining the house caught alight (post-1932). The store was never rebuilt, and the Post Office agency was later run by the Shannon family. As local populations dwindled, the sporting clubs suffered, with players transferring to nearby Toolibin.17 18

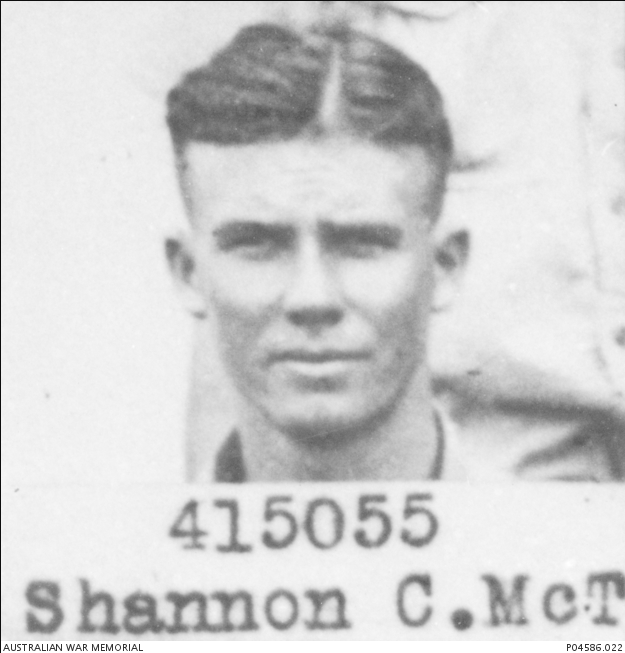

While the population shrank, Noman’s Lake did not entirely vanish. The community maintained essential connections; a telephone party line was erected in 1948 using voluntary labour, with farmers supplying the posts. The locality is still recognized as a place where key figures resided, such as Colin McTaggart Shannon, who enlisted in the RAAF in 1941 and was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross during the Second World War.19

The Modern Era

In the modern context, Noman’s Lake is classified as a rural location within the Shire of Narrogin. The 2016 Census recorded a population of just 50 people across the 177.76 square kilometre area, with only 13 private dwellings.20 21

The physical remnants of the past are preserved: the Nomans Lake Hall, featuring a corrugated iron roof and weatherboard walls, continues to be significant as a social meeting place and is still used today for annual Christmas Tree evenings and agricultural group meetings. The Hall was listed on the Municipal Inventory in 1996. Similarly, the site of the former school, designated as a historic site, is important for its association with the early settlers. The railway siding remains operational for wheat transport.

Inherit22

Crucially, the history of environmental degradation is now met with significant conservation efforts. The region, situated on Wiilman Noongar Boodja, is hosting large-scale ecological projects. In 2022, the Activate Tree Planting Festival returned to Nomans Lake, supported by Carbon Positive Australia, to plant 56,000 salt-tolerant native seedlings on Rosebrook Farm.23 These efforts aim to build ecological corridors, restore creek buffer areas, and expand habitat for native fauna, serving as a powerful reminder that the land cleared by the early pioneers must now be actively restored by modern custodians.

The journey of Nomans Lake mirrors the broader history of the Australian Wheatbelt—a testament to hard-won settlement, fleeting prosperity, and the enduring resilience required to adapt to a changing climate and economic landscape.

Timeline

- 1871: John Forrest examines the Yilliminning Pools in the general area, indicating pre-settlement knowledge.

- 1890s: Surveyor Oxley traverses the area; sandalwood cutters and shepherds are active nearby.

- 1904–1907: Land settlement is surveyed in the vicinity of Noman’s Lake.

- 1907 (June 2): Mr. E. Cardwell submits an initial request for a school service in the region.

- 1909 (June 6): The Lakes Progress Association requests a grant for materials to construct a Hall, intended also for use as a school.

- 1910 (January 24): Proposal made to erect a transportable tent school with quarters.

- 1910 (November 1): The Noman’s Lake School officially opens.

- 1912: Construction of the Agricultural Hall begins.

- 1912 (December 11): The Hall is officially opened by Mr. E.B. Johnston M.L.A..

- 1913: The railway line from Yilliminning to Kondinin is started.

- 1913: The children’s school prize distribution is held on Boxing night in the Agricultural Hall after being postponed due to a flood.

- c. 1913: Mr. and Mrs. Charlie Barnes build a store with a Post Office near the siding.

- 1915 (March 15): The Kondinin Loop Line (Yilliminning to Kondinin) is opened.

- 1915 (September 24): The area is officially classified and set apart as the “Townsite on the Yilliminning – Kondinin Railway” to be known as “Noman’s Lake”.

- 1920s: Formal sporting clubs begin to organize, including the Cricket Team and the Renown Tennis Club. A Wizard light is installed in the Hall.

- c. 1928: “The Lakes” Football Team is formed.

- Post-1932: The community store, owned by the McInnes family, is destroyed by fire and never rebuilt.

- 1938 (March 14): Noman’s Lake School ceases operation due to diminished pupil enrolment.

- 1941: Colin McTaggart Shannon from Nomans Lake enlists in the RAAF during the Second World War.

- 1948: A telephone party line is installed using local voluntary labour.

- 1996 (December 30): The Nomans Lake Hall is adopted into the Municipal Inventory (Category 3).

- 2013: Photographs illustrate that the railway siding and CBH Bin are still in use.

- 2016: Census data records the Nomans Lake population at 50 people.

- 2022 (June): The Activate Tree Planting Festival is held, planting 56,000 native seedlings to restore ecological corridors and address landscape degradation.

Map

Sources

- State Library of Western Australia n.d. 077097PD: Barry Kilpatrick and family in front of Nomans Lake School, ca.1920. Retrieved 3 Dec 2025 from https://encore.slwa.wa.gov.au/iii/encore/record/C__Rb4544060__SNomans%20lake__P0%2C6__Orightresult__U__X6?lang=eng&suite=def#attachedMediaSection ↩︎

- mindat.org, n.d. Nomans Lake Narrogin, State of Western Australia, Australia. Retrieved 3 Dec 2025 from https://www.mindat.org/feature-2064636.html ↩︎

- Heritage Council of WA, 2017. Nomans Lake Hall. Retrieved 3 Dec 2025 from https://inherit.dplh.wa.gov.au/public/inventory/printsinglerecord/452e3c13-f247-4fe1-925c-91f7932da2b4 ↩︎

- Astbury, Heidi and Chadwick, Lyn, 1987. Abbreviated History of Noman’s Lake. Extracts from “Noman’s Lake – A Collection of Memories”. Retrieved 3 Dec 2025 from https://www.narrogin.wa.gov.au/profiles/narrogin/assets/clientdata/documents/nomans_lake_history.pdf ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Foxes Lair, n.d. Nyanda Farm House. Retrieved 3 Dec 2025 from https://www.foxeslair.org/vanishing-farms ↩︎

- Heritage Council of WA, 2017. Nomans Lake School. Retrieved 3 Dec 2025 from https://inherit.dplh.wa.gov.au/public/inventory/printsinglerecord/5dccd030-fd21-464e-8f35-47411b843723 ↩︎

- State Records Office of WA, n.d. Noman’s Lake [Tally No. 504931]. Cartographic material retrieved 3 Dec 2025 from https://archive.sro.wa.gov.au/index.php/nomans-lake-tally-no-504931-1289 ↩︎

- Heritage Council of WA, Nomans Lake Hall: refers to the building of the hall ↩︎

- NOMAN’S LAKE. (1914, January 9). Great Southern Leader (Pingelly, WA : 1907 – 1934), p. 5. Retrieved December 3, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article157063696 ↩︎

- Astbury & Chadwick, p.3: Refers to the use of a Wizard light in the hall ↩︎

- Astbury & Chadwick, p.2: Refers to the establishment of the rail siding ↩︎

- Noman’s Lake Cricket Notes (1927, October 28). Great Southern Leader (Pingelly, WA : 1907 – 1934), p. 5. Retrieved December 3, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156977133 ↩︎

- Astbury & Chadwick, p.5: refers to sporting facilities ↩︎

- State Records Office, 2025. Search results for Nomans Lake. Retrieved 3 Dec 2025 from https://archive.sro.wa.gov.au/index.php/informationobject/browse?topLod=0&query=Nomans+Lake ↩︎

- Heritage Council of WA, Nomans Lake School: refers to closure of the school ↩︎

- Astbury & Chadwick, p.4: refers to the school ↩︎

- Australian War Memorial, n.d. Portrait of 415055 Colin McTaggart Shannon from Nomans Lake, East Narrogin, Western Australia. Photograph in the public domain retrieved 3 Dec 2025 from https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1098692 ↩︎

- Australias.Guide, n.d. Nomans Lake. Retrieved 3 Dec 2025 from https://australiasguide.com/wa/location/nomans-lake/ ↩︎

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016. 2016 Census All Persons QuickStats. Retrieved 3 Dec 2025 from https://abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2016/SSC51113 ↩︎

- Heritage Council of WA, 2017. Nomans Hall. Retrieved 3 Dec 2025 from https://inherit.dplh.wa.gov.au/public/inventory/details/452e3c13-f247-4fe1-925c-91f7932da2b4 ↩︎

- Active Tree Planting, 2022. Activate Noman’s Lake 2022. Retrieved 3 Dec 2025 from https://activatetreeplanting.org.au/nomans-lake-2022/ ↩︎

Further Reading

- Noman’s Lake – A Collection of Memories by Heidi Astbury and Lyn Chadwick

- Merredin to Yilliminning railway line

- Shire of Narrogin