What was school like for the children and teachers of Western Australia’s Ghost Towns?

In the years of rapid growth of mining communities, timber camps and the railways, (which encouraged the opening up of much agricultural land), schools opened and closed rapidly, sometimes even in the same community as the population grew and shrunk and grew again. Schools were indeed perfect barometers of the rise and fall of centres of population.1

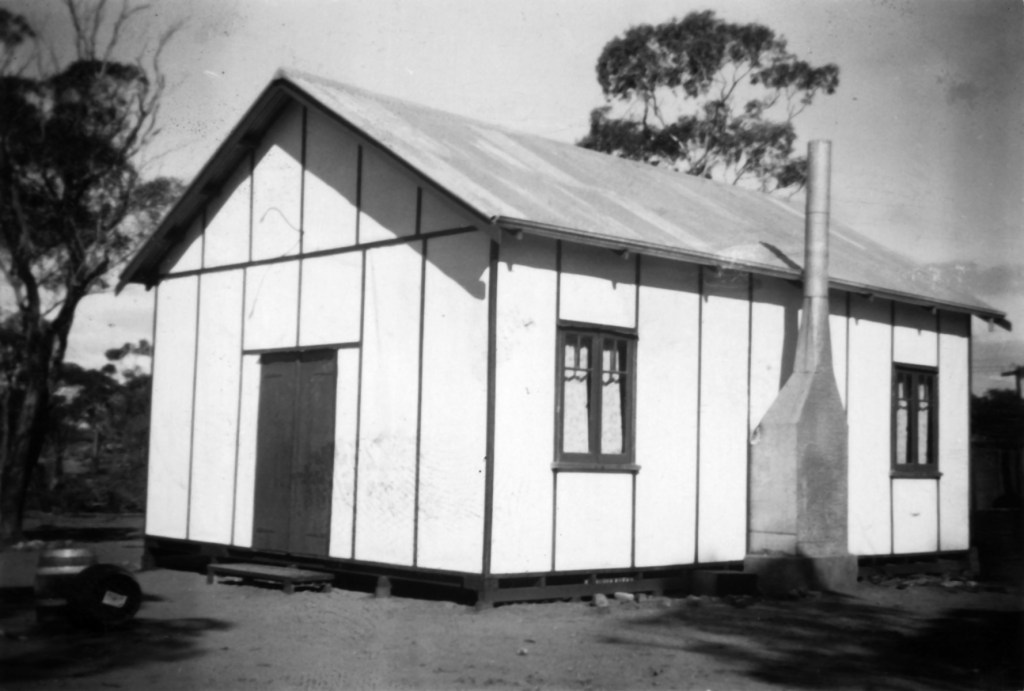

During the years of the early 1900s, Western Australia was fortunate to have a head of the Education Department who believed that every child in Western Australia, no matter how remote their home was, should have access to education.2 This thinking caused many tiny schools to open. Sometimes as few as 10 children were needed before a school could be established. Schools were in tents, slab huts, transportable buildings with canvas walls and a tin roof, in the back rooms of halls or churches and in school buildings, which were often erected by the community.

Both the pupils and their teachers did it tough in these bush schools. Pupils often walked long distances to school or if they were lucky rode horses. Pupils were expected to attend school if they lived 2 or 3 miles away, (the younger children under 9 were only expected to walk 2 miles, while those over 9 could walk longer distances). School ‘buildings’ got very hot in summer and were freezing in the winter months. School rooms were also home to local wildlife such as mosquitos, flies, frogs, lizards, mice, and snakes.

Teachers were under pressure to not only teach but keep the school grounds looking good, either making a garden or, at the minimum, planting trees. Sometimes this resulted in children spending a lot of their school time in the bush gathering materials for fencing the school, missing out on their education, and ruining their clothes.4

A teacher’s first difficulty when appointed to a bush school was finding out where the school was and then how to get there. Once they arrived at a remote railway siding most of the community were there to meet them, especially if the teacher was a young female.

Housing for the teachers was also a problem. A community that wanted a school had to supply accommodation for the teacher. Often the teacher boarded with a local family, and most families lived in very basic houses. The teacher sometimes shared a room with older children and female teachers were usually expected to assist with household chores as well as paying board. Teachers got to school the same way as their pupils, by walking up to three miles or in some places riding a horse.

Once the teachers got to school they had the daily challenge of teaching a class of pupils whose ages ranged from 5 to 14. After the school day was finished the bush school teachers needed to clean the school, (for which they were paid a little extra, and complete hours of paperwork – such as ensuring attendance records were up to date, writing letters to the Education Department or answering such letters, and having written plans in place for all grade levels they taught.

Up until the 1930s the majority of schools outside West Australian towns had less than 20 pupils. The government of that day put education as their second highest priority, after ensuring a satisfactory food supply for the state.5 Eventually as people began moving to larger towns, there was a move to centralise schooling and pupils began to be bussed to larger schools.

The era of small schools in the bush was drawing to a close. Thousands of children attended small bush schools in Western Australia. Did they receive an education that was comparable to the children in the larger towns? In many cases yes, due to the efforts of their intrepid teachers and their parents who ensured that their children were up and off to school.

As children across Western Australia return to school this week in their air-conditioned classrooms, let’s take a moment to remember what it was like for many of the children in years gone by in lonely schools down the dusty tracks or forest paths.

SOURCES

- Quote attributed to an Inspector Miles in 1912 in McKenzie, J.A. (1987). Old bush schools: life and education in the small schools of Western Australia 1893 to 1961. Doubleview, Australia: Western Australian College of Advanced Education. P. 7. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks/7075 ↩︎

- Cecil Andrews, an Oxford graduate, was head of the Western Australian Education Department from 1913 to 1927. ↩︎

- State Library of Western Australia. Spargoville School. Retrieved from https://purl.slwa.wa.gov.au/slwa_b1974926_3 on 29 Jan 2024. ↩︎

- Bush Schools: A Plea for the Children. Letter to the editor of the Bunbury Herald and Blackwood Express, 26 November 1920. p.6 ↩︎

- McKenzie, J.A. (1987). Old bush schools: life and education in the small schools of Western Australia 1893 to 1961. Doubleview, Australia: Western Australian College of Advanced Education. P. 14. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks/7075 ↩︎

- State Library of Western Australia. School children, Lewis and Reid No. 2 Mill, near Allanson, Western Australia, ca. 1920. Photograph retrieved from https://purl.slwa.wa.gov.au/slwa_b6797766_2 on 29 Jan 2024. ↩︎