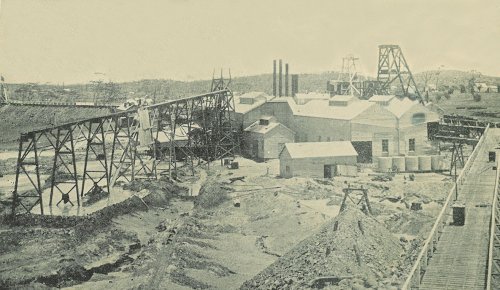

Cossack in 1886 was a frontier town in one of the most isolated colonies in the world. It was a centre for pearling and pearl shell fishing and the entry point for pastoralists who established extensive stations. By 1886 Cossack had a stone wharf and several other stone buildings such as the Post and Telegraph Office and a Mercantile Store, but not a lot of other substantial buildings. How did it attract an operatic performance by the most popular Opera Troupe of the decade?

Perth loved Mr Stanley’s Opera Troupe. It played to huge audiences and received mostly glowing reviews. The Railway employees took up a collection so they could present Mr and Mrs Stanley a gold ring and earrings as a token of their esteem and appreciation1. A Fremantle harbour official stole flowers, roses, and bouquets to bestow upon sundry members of Stanley’s Opera Troupe before they left Perth2. An ode of farewell to the players was written and published in the Perth news in October 18853.

Mr Stanley’s Opera Troupe and other itinerant theatre groups used the coastal steamers to travel around Australia4. In early 1886, Mr Stanley was taking his Opera Troupe to Singapore and to get there travelled on a coastal steamer that called in at Champion Bay, Gascoyne, and Cossack before leaving Australia.

Ever the entrepreneur, Mr Stanley used his time in port in Cossack to his advantage and had his Opera Troupe perform two shows at Roebourne before performing their last show in Cossack. The Cossack show was a performance of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Pirates of Penzance and took place on Saturday 13 March 18865.

I have been unable to find a review of the Cossack performance of this opera, but when it was performed in Perth the previous October it received a review that said –

The acting was very spirited, the costumes pretty, the children acquitted themselves admirably in their dancing, but the actors said their words very quickly, and some songs were ‘absolutely gabbled’.6

Who was Mr Stanley and how did he get into show business? The only biography I can find of Harry Stanley was supplied by him to a Perth newspaper in 18857. His life had so many self-reported highlights and makes me wonder if he embellished his life story.

Stanley was born in England but after a childhood supposedly touring Europe he joined the Royal Navy and served in the Crimean War. He came to Australia in the mid-1850s, worked on a steamship out of Melbourne before heading for the goldfields, where he was stuck up by the notorious bushranger Black Johnston. After failing to find his fortune, Stanley joined a Theatrical Troupe where he found success playing the character of Rob Roy. He moved from Troupe to Troupe, in various roles before forming his company and managing the Lyceum Theatre and Hotel in Sandhurst.

Stanley travelled to South Africa in 1870 with the American War Panorama Troupe but was unfortunately shipwrecked on the way. Luckily he saved the Panorama and just so happened to be on the diamond fields of Kimberley when they raised the British flag. Stanley was received by African presidents and kings during that trip. He spent time as a guest of the Nizam at Hyderabad and was asked to lecture on war to the Sikh regiments. Stanley then went to Burma, where he was presented with a medal from the King and subsequently travelled to Siam, where he stayed at the palaces of the kings.

Perhaps colourful renditions of life stories come with show business. After leaving Cossack it was reported that Mr Stanley was struck insensible by lightning for three hours while on deck of the SS Natal8. Fortunately, Stanley had recovered by the time he reached Singapore.

Stanley and his Opera Troupe seem to have spent the next few years performing in the East, visiting “the colonial port cities with large European populations where there was a high demand for the sort of shows he staged9.

Stanley returned to Australia to settle some business in 1896, but while in Newcastle his heart condition suddenly worsened, and he died (without a will). Stanley was nearly 60 years old10. The Freemasons in Calcutta raised money for his wife and daughters to return to Australia. Entertainments such as Mr Stanley’s Opera Troupe were facing competition from newer forms of entertainment such as roller skating. The story of Harry Stanley and his Opera Troupe is a colourful one. What other larger than life people’s stories are awaiting discovery in Western Australia’s Ghost Towns?

Sources

- Presentation to Mr and Mrs Stanley. The Inquirer and Commercial News, February 1886, p. 5. ↩︎

- Perth Local Court. Western Mail, 2 January 1886, p. 10. ↩︎

- Farewell to Stanley’s Opera Troupe. The Daily News, 6 November 1885, p. 3. ↩︎

- YU Elysia, 2020. Australian Itinerant Theatres as Colonial Cultural Assimilation https://www.tca.hku.hk/post/australian-itinerant-theatres-as-colonial-cultural-assimilation

Accessed 20 March 2024. ↩︎ - Roebourne Letter. Western Mail, 13 March 1886, p. 16. ↩︎

- The Pirates of Penzance. The West Australian, 12 October 1885, p. 3. ↩︎

- Biography of Mr. Harry Stanley (1885, September 26). The Herald (Fremantle, WA : 1867 – 1886), p. 3. Retrieved April 13, 2024, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110070728 ↩︎

- Local. The West Australian 13 April 1886, p. 3 ↩︎

- YU Elysia, 2020. Australian Itinerant Theatres as Colonial Cultural Assimilation https://www.tca.hku.hk/post/australian-itinerant-theatres-as-colonial-cultural-assimilation. ↩︎

- Newcastle News. The Maitland Weekly Mercury, 2 May 1896, p. 5. ↩︎