Digitized and available via the National Library of Australia; this work is out of copyright and free to use for public purposes.

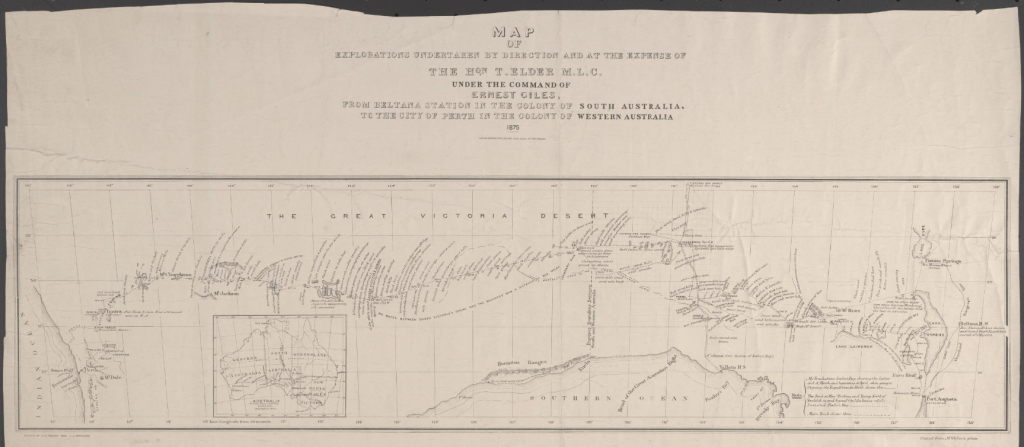

Among the explorers who expanded knowledge of the Australian interior in the nineteenth century, Ernest Giles occupies a distinguished place. His 1875 expedition, financed through the generosity of the South Australian pastoralist and politician Thomas Elder, represented a major advance in geographical discovery, demonstrating both the challenges of crossing the continent’s deserts and the determination required to overcome them.

At the time, vast tracts of inland Australia remained uncharted, and speculation abounded about the potential of the interior for settlement and communication. Earlier surveys by Baron Ferdinand von Mueller and Augustus Gregory in the 1850s had suggested the broad character of these lands, but much remained unknown. Elder, convinced of Giles’s skill as a leader and of the value of camels for desert travel, offered to fund a new expedition to establish as direct a route as possible between South Australia and Western Australia.

The expedition commenced from Port Augusta in May 1875, and the true crossing began on 27 July from Youldeh. Giles’s party included nineteen camels, provisions for eight months, and equipment for carrying water, all vital in a region where survival could never be taken for granted. From the outset, the expedition encountered formidable obstacles. Sandhills, spinifex, and dense mallee scrub made progress slow, while the scarcity of permanent water dictated the pace and direction of travel.

In an early attempt to cover more ground, Giles divided his men: he himself explored westward while William Tietkens and Young struck north in search of the Musgrave Ranges. Both ventures revealed the inhospitality of the land. Giles discovered saline springs and barren scrub, with no signs of animal or human life. His companions fared little better, returning without sighting the Musgraves or finding fresh water.

At one point disaster nearly struck when the camels bolted. The animals were eventually recovered after a long chase, but had they been lost the expedition would have faced almost certain failure. The precariousness of the journey was underlined again in September, when the party endured seventeen days and 325 miles without locating water. Exhaustion and despair led some members to propose slaughtering camels for survival. Giles, however, refused to abandon hope, and perseverance was rewarded when the party discovered a hidden lake. This crucial water source, named Queen Victoria’s Spring, ensured their survival and allowed them to continue.

From this point the nature of the country began to change. Granite outcrops and quartz appeared, bringing with them more reliable supplies of water and pasture. Yet dangers remained. At Ularring, Giles and his men encountered a large and well-organised Aboriginal group who mounted a determined attack. The explorers’ firm defence forced the assailants to withdraw, and the incident remained Giles’s most serious conflict with Indigenous Australians.

Approaching Mount Churchman, Giles noted that the surrounding terrain did not match Augustus Gregory’s earlier chart, which had described the area as flat. Instead, Giles observed ranges of iron-rich and volcanic-looking rock, so magnetic that compass readings proved unreliable. These discrepancies highlighted both the difficulties of accurate surveying and the continuing importance of first-hand exploration.

On 4 November 1875, after a journey of some 2,500 miles, Giles and his party finally reached settled country at Tootra, a sheep station owned by the Clunes brothers in Western Australia. Their safe arrival was greeted with warm public acclaim. Although the expedition had not revealed fertile lands ready for immediate settlement, it had achieved much in both scientific and practical terms. A direct east–west route had been established, new water sources had been identified, and the suitability of camels for such arduous work had been conclusively demonstrated.

The 1875 expedition stands as a testament to Giles’s qualities as an explorer. His leadership, endurance, and refusal to succumb to despair carried his party through regions he described as “utterly devoid of animal life” and “utterly forgotten by God.” While the lands traversed were not destined for agricultural development, the knowledge gained contributed to the broader project of mapping and understanding the Australian interior.

In this respect, Ernest Giles belongs to the company of Gregory, Stuart, and Eyre—men whose journeys across the deserts and ranges expanded the limits of colonial knowledge and shaped the geographical imagination of nineteenth-century Australia. His 1875 crossing of the continent remains one of the most remarkable achievements of its era, demonstrating the extraordinary perseverance required to chart a land as unforgiving as it is vast.

AUTHORS NOTE: This article is based on an 1876 correspondent’s account of Giles’s expedition.1 More recent accounts of the Giles expedition have questioned the contemporary accounts of the Ularring incident.

Sources

- ERNEST GILES’S EXPLORATION’S, 1875. (1876, April 22). The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954), p. 5. Retrieved August 27, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article202161961 ↩︎