A Curious Case in Higginsville, 1907

In the early days of January 1907, the quiet mining town of Higginsville, Western Australia, found itself at the centre of a curious legal drama. Nestled in the Goldfields-Esperance region, Higginsville had only recently been gazetted as a townsite that same year. Named after prospector Patrick Justice Higgins, the settlement was a modest but active hub for goldfield workers, with a population that hovered around a few dozen. Life in Higginsville revolved around the rhythms of mining, the railway, and the local hotel—often the social heart of such frontier towns.

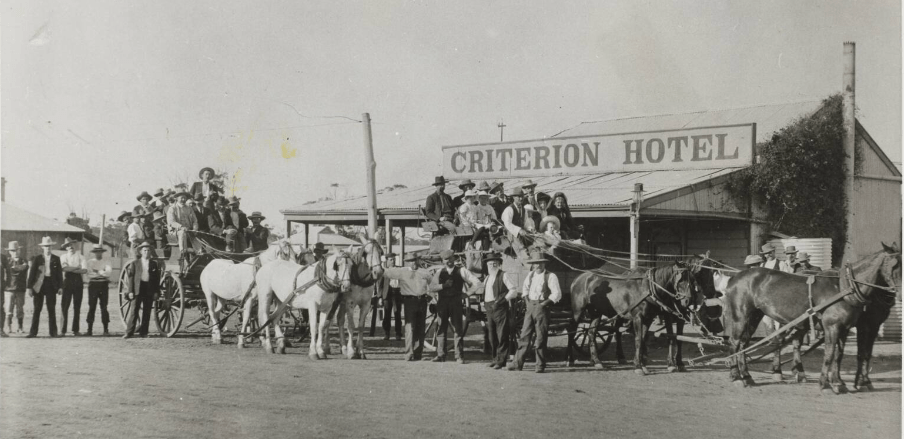

Photograph in the collection of the State Library of Western Australia1

It was at this hotel that the alleged crime took place. On the night of January 3rd, Charles Jacobson, a carpenter and long-time resident of the goldfields, was accused of breaking and entering the licensed premises of Hannah Warburton with intent to commit a crime. The trial commenced the following afternoon before the Chief Justice and a jury of twelve, with Crown Solicitor A. E. Barker prosecuting and Mr. F. H. Rickarby defending the accused.

According to the prosecution, Jacobson had been among the last patrons in the hotel bar before closing. Later that night, a disturbance was heard by one of Warburton’s sons, who, along with another man, discovered that entry had been forced through the beer cellar. Jacobson was found inside, barefoot, with his boots left outside the flap—an odd detail that would become central to the case.

The Crown argued that the cellar flap had been opened with force, suggesting intent. Jacobson’s proximity—his camp lay just 50 yards away—added to the suspicion. Though he claimed to have fallen into the cellar and struck his head, the prosecution questioned his motives. “If he only wanted to steal a drink,” Barker noted, “it was a crime.”

Testimonies from Hannah Warburton and her family, as well as Harry King and Constable Finch, supported the prosecution’s narrative. Jacobson, however, maintained that he had no recollection of entering the cellar, attributing his condition to drunkenness and fatigue. He insisted he had returned home to his two young sons after the incident.

The defence leaned heavily on the testimony of Jacobson’s children. Carl Jacobson, aged 11, recounted seeing his father leave the camp after being invited for a drink by an unknown man. He described watching his father from a hole in the tent wall and later witnessing him return, bruised and disoriented. His twin brother, Thomas, corroborated the account.

Mr. Rickarby, in his address to the jury, emphasized the lack of clear intent and the possibility of an accident. Mr. Barker, confident in the simplicity of the case, chose not to offer a rebuttal.

The court adjourned at 4:15 p.m. on 22 March 1907, with the Chief Justice set to deliver his summation the following morning. When proceedings resumed, the jury returned a verdict of acquittal. Jacobson’s story—that he had accidentally fallen into the cellar and had no knowledge of any attempted robbery—was ultimately believed. The case closed not with condemnation, but with a reminder of how easily circumstance can be mistaken for intent.

Author’s Note

This article was prepared from contemporary accounts found in newspapers from Kalgoorlie 2, Adelaide 3 and Sydney.4

- State Library of Western Australia. Stage coaches prepare to leave for Coolgardie. Photograph, 1908. http://purl.slwa.wa.gov.au/slwa_b6580636_2 ↩︎

- ALLEGED BREAKING AND ENTERING. (1907, March 23). Kalgoorlie Miner (WA : 1895 – 1954), p. 3. Retrieved September 4, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article90399939 ↩︎

- WESTERN AUSTRALIA. (1907, March 25). The Register (Adelaide, SA : 1901 – 1929), p. 6. Retrieved September 4, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article58128560 ↩︎

- WESTERN AUSTRALIA. (1907, March 25). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), p. 7. Retrieved September 4, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article14858266 ↩︎