Author’s Note: The information for this interesting piece of WA’s history comes from two newspaper articles, both of which are available on Trove.1 2

In the late 1890s, the town of Kanowna was a place where “gold fever” was not just a metaphor—it was a way of life. With a population surging toward 12,500, the air was thick with the dust of thousands of miners seeking their fortunes in the “deep leads” of the Western Australian scrub. But in July 1898, this fever reached a delusional breaking point in an event that would become one of the most legendary pranks in Australian history: the hoax of the Sacred Nugget.

The Rumour of the Sickle

The mystery began when reports circulated through the Eastern Goldfields of a monster lump of alluvial gold. Unlike the usual “slugs,” this one was described as being shaped like a sickle and valued at a staggering £6,500 ($A9.9million at today’s gold value).

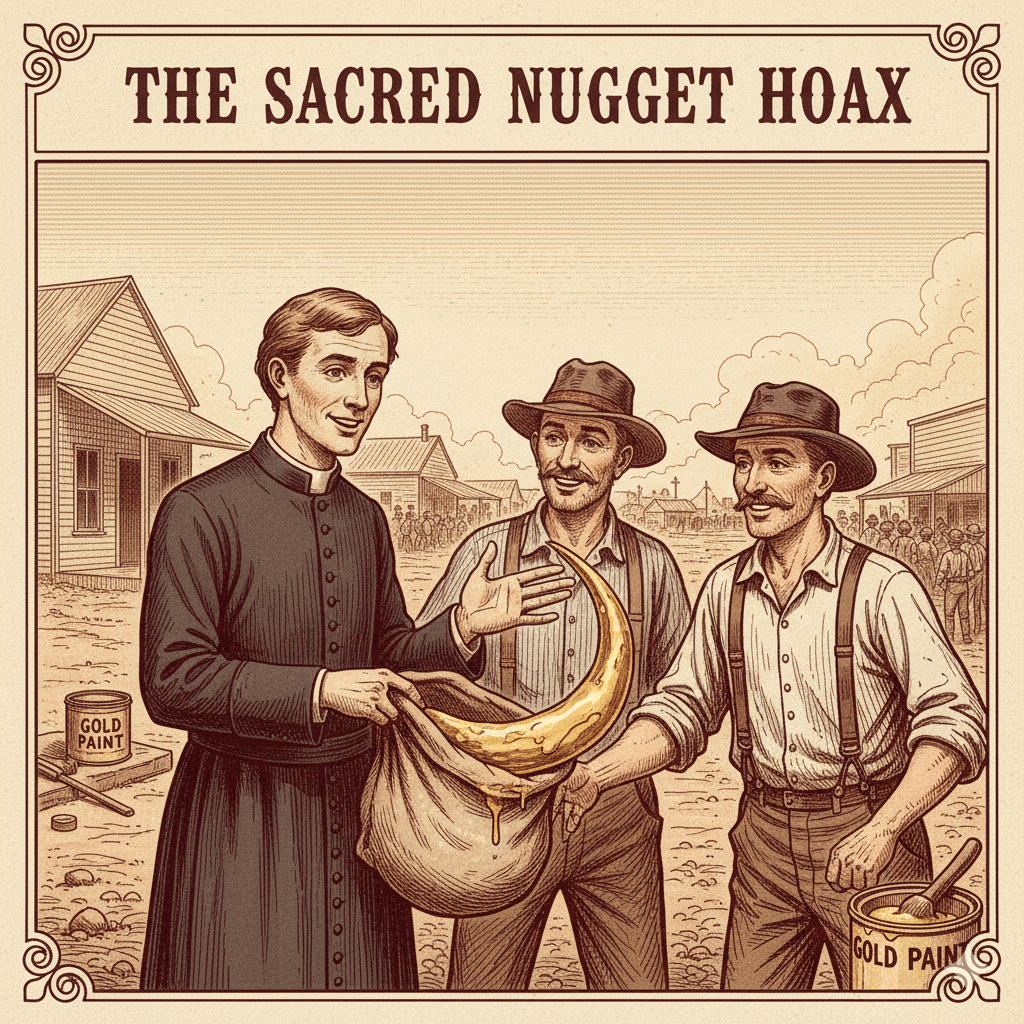

Secrecy surrounded the find. The discoverers remained anonymous, and the nugget was supposedly hidden away, sight-unseen by the public. However, one man claimed to have seen it: a young, naive priest named Father Long. Because of his involvement, the treasure earned the nickname the “Sacred Nugget”.

7,000 Men and a Hotel Balcony

By August 1898, the mining community’s frustration with the secrecy had reached a boiling point. To quell the unrest, it was promised that the exact location of the find would be revealed publicly.

On Thursday, August 11, at 2:00 p.m., Kanowna stood still. An estimated 7,000 eager men—including a special contingent of 2,000 who had rushed over from Kalgoorlie—massed in front of Donnellan’s Hotel. A strong body of police was required to hold back the mob as a pale, nervous Father Long stepped onto the upstairs balcony.

After making the crowd promise to ask no further questions, he delivered the “pay-line” they had been waiting for:

“The nugget was found a quarter of a mile this side of the nearest lake on the Kurnalpi Road…”.

The Great Stampede

The announcement triggered a scene of absolute chaos. Before the priest could even finish speaking, the crowd erupted. Thousands of men on horses and push-bikes charged toward the Kurnalpi road, trampling one another in a desperate race to peg out claims. Within hours, hundreds of acres were pegged, and men began digging furiously.

Days passed into weeks. No gold was found. The “Sacred Nugget” was nowhere to be seen, and even the Union Bank in Coolgardie—where the gold was allegedly lodged—denied knowing anything about it. The “gold fever” began to turn into a cold realization: they had been had.

The Confession: Scrap Iron and Gold Paint

The truth, revealed long after Father Long’s untimely death from typhoid at age 27, was far more mundane than a hidden treasure. The hoax was the brainchild of two local pranksters, referred to in historical accounts as “Smith” and “Jones”.

The duo had found a heavy, semi-circular lump of scrap iron in a hotel backyard. Seeking a bit of “tomfoolery” to wake up the town, they bought a tin of gold paint from a local store, coated the iron, and shoved it into a bag.

The prank took an unexpected turn when they literally bumped into Father Long while carrying the “find”. When the priest excitedly asked if they had gold in the bag, the men realized that involving a man of the cloth would make the gag “funnier than ever”. They played their parts as “highly skilled actors,” and the naive priest, who knew nothing of the hungers gold bred in men, fell for the ruse completely.

A Lasting Legend

Though the “Sacred Nugget” never existed, its legacy endured. While some grumbled that publicans had tricked the priest to bring trade to Kanowna, most felt a strange lack of resentment toward Father Long, believing he had been a sincere victim of a clever trick. Today, while the town of Kanowna is a ghost of its former self, the story remains a cautionary tale of how easily a few pennies’ worth of paint can lead 7,000 men into the desert

Sources

- OUR STRANGE PAST (1953, November 19). Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 – 1954), p. 10. Retrieved December 31, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article39358444 ↩︎

- Some facts about HISTORIC NUGGETS (1950, September 14). Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 – 1954), p. 36 (COUNTRYMAN’S MAGAZINE). Retrieved December 31, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article39104972 ↩︎