“An account of a new settlement is always interesting, but when Australian colonists venture into an entirely new country, and in addition to settling and stocking the land, discover a new industry that employs hundreds of men—both black and white—it becomes even more fascinating. Just two years ago, many parts of the district to be described here were only accessible by armed bands. Enterprising settlers are now sending down pearl shells and wool from the very spot where Panter, Harding, and Goldwire, the surveyors, were murdered by the aboriginals without provocation.

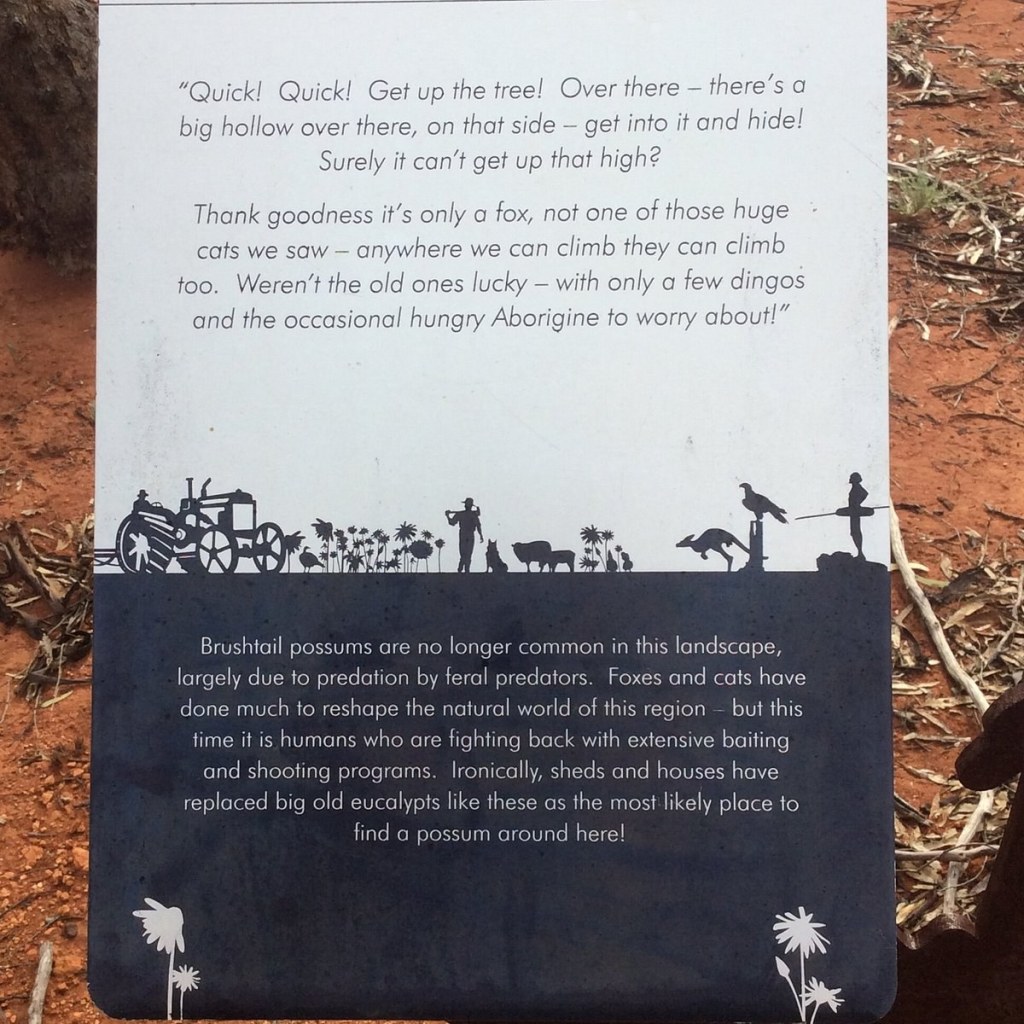

“The settlement of the Nicol Bay district, as it is known, has been quicker than any other part of Australia. It is heartening to note that the relationship between the aboriginals and the white settlers is now more friendly and satisfactory than can be seen elsewhere on the island. The prosperity of the largest part of the community relies entirely on the preservation and assistance of the natives; without their help, the settlers might explore the reefs but would not collect enough shells to repay their investment. The natives’ sharp eyesight and the large numbers in which they can be employed make their cooperation invaluable. Their usefulness serves as the best guarantee for their proper treatment. In fact, any injustice is often more likely to be borne by the whites than the blacks. Many natives gather food for themselves and their families during neap tides and walk away just when their services are needed.

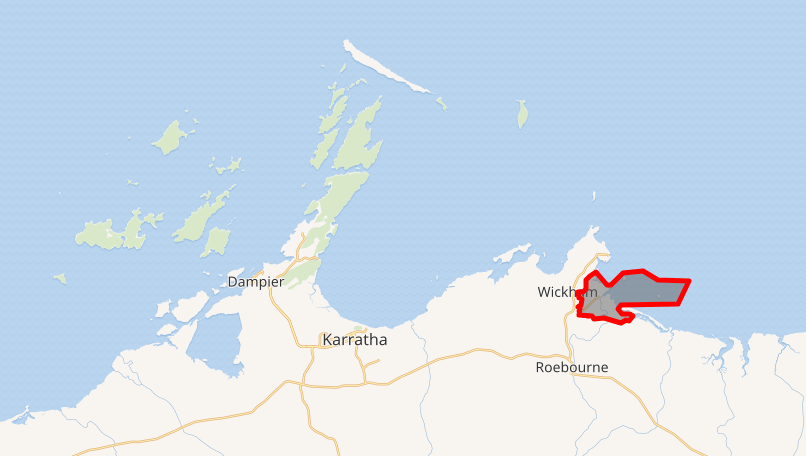

“Port Walcott, the headquarters of the small boats engaged in pearl fishing and the port of entry for vessels from Fremantle that supply the settlement with stores, is located about a mile inside Butcher’s Inlet, or Tien-Tsin Creek, named after the first significant vessel that ever anchored in the bay outside. It is situated at latitude 20°40’ south and longitude 115° east, about 180 miles east of the North-West Cape. Despite bearing the high-sounding name of Port Walcott, the settlement has no better claim to the title than a single house and the hull of the New Perseverance, with several smaller dwellings that resemble mia-mias. However, as a government township has been surveyed and partly sold, it is likely that the town will soon have at least an orthodox hotel, a store, and a doctor’s shop. For now, Messrs. Knight and Shenton’s place of business onshore, and the cabin of the hulk, serve all purposes. Butcher’s Inlet has enough water on the bar to admit vessels of a hundred tons at high tide. During low water spring tides, the inlet can almost be crossed on foot. The tide along the northwest coast ranges from 17 to over 30 feet, a stark contrast to the west coast, where there is barely any rise or fall.

“During the fishing season, which begins around the first week in September and ends in April, the port is rather dull and unremarkable. However, at the close of the season, or during the neap tides, if any festivities are expected in Roebourne, the area comes alive with bustle and activity. The scene is a perfect representation of tropical Australian life. A wide mangrove creek is lined with a dozen boats, ranging from 3 to 10 tons, moored along the bank, or lying helplessly in the muddy sand at low tide. Perhaps a larger Swan River trader will be docked with clean-scraped spars and an awning spread. White settlers, dressed as minimally as decency permits, walk about, wearing fly-veils to protect their faces from the swarming flies. Aborigines from all parts of the coast are present, some cleaning and sorting pearl shells, chipping off sharp, colorless edges and tossing them as though they were worth little—when in fact, they are worth at least £150 per ton. Others are practicing spear throwing with small reeds or giges. The failure of any party to deflect a spear with their shield leads to uproarious yells of derision from one side and joy from the other. But the majority are lying on the hot sand, singing monotonous chants, accompanied by the scraping of a shell against a piece of stick held against their shoulder like a fiddle.

“Roebourne, the capital of the new country as Western Australians term the district, is located 11 miles southward, inland of Port Walcott. For some distance, the road crosses a marsh covered by the tide at high springs, making for difficult travel. All goods for the stations are brought up the creek to a jetty. From there, it is just five miles to Roebourne, and with the exception of one small marsh, the road is not too bad. The township of Roebourne consists of about twenty houses built at the base of Mount Welcome. The resident magistrate’s house and the government offices are the most prominent buildings, sitting higher up the mount and away from the threat of malaria or floods from the Harding River, whose waters sometimes get too close for comfort during heavy tropical rains. There are two rough but comfortable hotels, three stores, a butcher’s shop, a blacksmith’s forge, a large stockyard, and, of all things in such a place, a hairdressing salon. This is the current capital of North-West Australia.

“Roebourne is not without its charm, especially when the desert pea—native to the area—blooms in full flower. It has two key scenic features: mountains and a river. The Harding River is a permanent freshwater source. Races are held on the plain near the township every June, during which time nearly all the settlers and pearl fishers, numbering about a hundred, gather. The races may not be of great significance in such a small district, but for joviality and good cheer, a Roebourne race meeting could serve as an example for larger communities. Indeed, there is a noticeable absence of the ruffianism often found in new Australian settlements.

“The nearest station to Roebourne is Mr. Leake Burges’s, located 24 miles away, and carrying some 7,000 sheep. The main station is the “Mill Stream” on the Upper Fortescue, owned by Messrs. McRae, Howlitt, and Mackenzie, formerly from Victoria. Mr. Hooly had squatted on the Ashburton River, 200 miles westward and 80 miles from any neighbor, but constant attacks by the blacks, who are perhaps the most savage and untamable in Australia, forced him to move his flock to the Fortescue. The murder of the third shepherd last year led Mr. Sholl, the magistrate, to swear in a party of special constables to apprehend the murderers or, failing that, teach them a lesson. A party of six men set out to the scene of the murder and “dispersed” some of the hostile natives, who were caught spearing horses and cattle, though not without determined resistance.

“It is still uncertain whether station properties in this part of Australia will repay the investment. It has yet to do so, despite the encouragement of leases at nominal rents and other privileges given by the West Australian Government. This is partly due to the difficulty in preparing wool, the high cost of shipment to Fremantle, and the need for transshipment to England. The region also lacks mechanical means of wool preparation. Communication with Swan River is possible by land. During one food shortage in the settlement, a party rode to Perth to dispatch a vessel, and Mr. Hooly, alone and unaccompanied, completed a remarkable feat considering that the country for over 500 miles is uninhabited except by wild and potentially hostile blacks.

“There is a great scarcity of fresh water on the west coast, though the Nicol Bay country does not suffer as much in this regard. The primary drawback is that the best grazing areas are also the driest. Approximately twenty boats, mostly under eight tons, are engaged in pearl fishing. With the wind from the southward and south-east for most of the year, any vessel with a deck, no matter how small, can easily run before it until the North-West Cape is rounded, where the water remains calm due to the continuous reefs and islands. These boats generally carry two white men, who, before setting out to gather the shells, pick up as many aboriginals as possible along the coast. However, the number of boats involved in the trade, combined with losses from smallpox and other factors, has made it difficult to find enough aboriginals to properly search for the pearl oysters. As a result, the trade is no longer as profitable as it once was. Even for the most experienced fishermen, under the most favorable conditions, it is only a fair return on their investment.

“This season, two vessels from Sydney went to the fisheries but have since returned and are now in quarantine due to smallpox. Even if they had returned in good health, the expense of a trip to the South Sea Islands, where natives must be returned, as well as the cost of provisions, boats, wear and tear, and wages, makes the return on the investment not comparable. The “Kate Kearney” returned with eight tons, worth £150 per ton, and the Melanie, a large vessel, only brought back ten tons. New ground may still be found, as the fisheries currently range from Exmouth Gulf to the Annapanam Shoals, and it is known that Malay proas have visited the north coast of Australia for many years. A schooner named the Argo was outfitted from Swan River last season and ventured as far east as Camden Harbour. However, the aboriginals they had brought along ran away just as they had found valuable shell. These unfortunate men would likely never return home, as they would be speared by the first strong camp they encountered.

“Aboriginals, though well-treated, often long to return to their native lands. When taken to Fremantle, they are shown the pleasures of civilization, and, after a week, they are eager to return north. Their language is easy to learn, though dialects differ from river to river. The Eastern dialect is considered the standard, and both whites and blacks accommodate themselves to it. This means that a good understanding of the language used between Butcher’s Inlet and the De Grey River allows communication with natives from any part of the fishing coast.

“The natives primarily eat nalgo, a bulb from a species of grass. It is very palatable and resembles chestnuts when roasted. Women gather it from sandy spots along river beds or marshes. The men use two types of spear: a lighter hunting spear, thrown from a rest, and a fighting spear, thrown by hand. They also use boomerangs, clubs, and a short stick, which they throw with great dexterity. Their marriage customs are quite curious, and any breach of the intermarriage rules is punishable by death. They are divided into four great tribes or families, and in the event of a death in a camp, they may kill a fighting man from a neighboring tribe to balance their strength. They also kill those afflicted with contagious diseases, such as smallpox, which recently struck the South Sea Islanders aboard a Sydney vessel. Their dietary laws are strictly observed, and nothing will induce a native to eat tabooed food. Superstition plays a large role in their lives; they are in constant fear of a demon named Juna, responsible for all death and disease. It is believed that Juna chokes his victims.

“In their own way, the natives are great astronomers, with names for all the major constellations, such as the Large and Lesser Kangaroo and the Emu. They can distinguish fixed stars from planets. When answering questions, they tend to exaggerate, and they have legends of extraordinary men from far inland. This brief description of this fascinating race only scratches the surface, but more detailed accounts will intrigue those interested in ethnology.

“The pearl shell is not an oyster but an “avicula,” composed of nacreous laminae. It can be cut and polished in any part and is in high demand in England and on the Continent for inlaying and ornamental purposes. The shell is typically half embedded in the sandy mud and can only be harvested at low water during spring tides. Several large pearls have been found, one of which was sold in England for £260 last year.”