I just came across this article in the Sunday Chronicle of 12 Dec 18971. It struck my funny bone and so I wanted to share it with you!! Perhaps, given the sombre nature of the background to the article, that says something rather dark about my sense of humour?

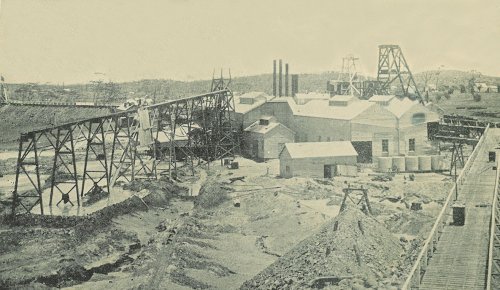

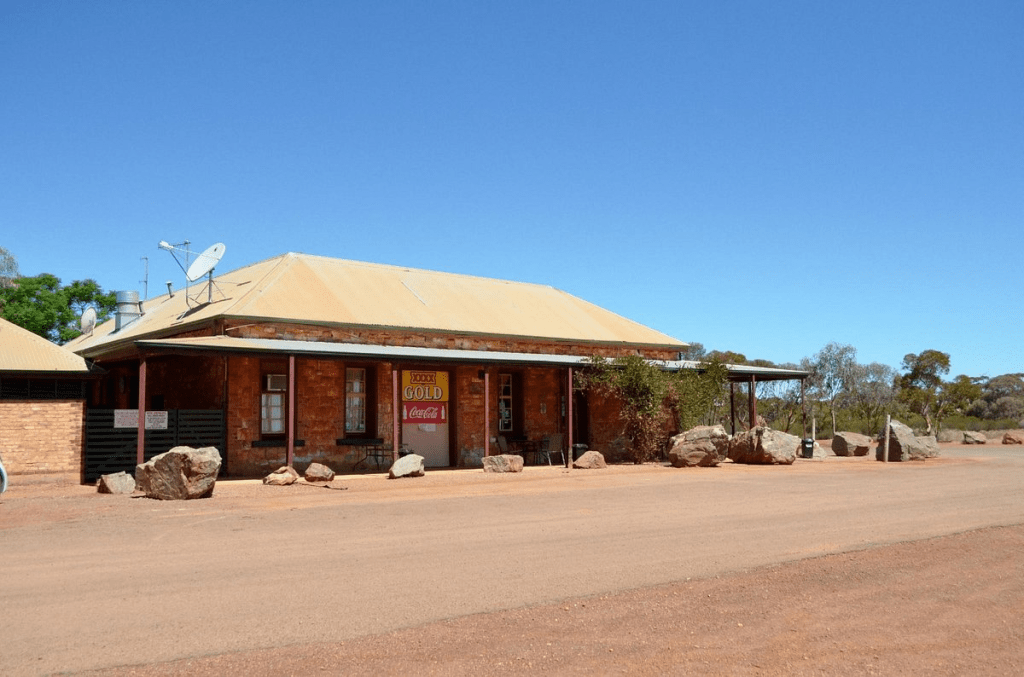

Steps are being taken (says the Morning Herald’s Menzies correspondent) to organise another search party to look for the man M’Innes, who was lost 12 months ago while journeying from Menzies to Donkey Rocks. He is supposed to have perished between Menzies and Goongarrie Lake.

This reads very curiously to us. There were search parties organised about the time that the man was lost and they were unsuccessful. Have the Menzies people become so thoroughly embued with the West Australian spirit that after 12 months they must institute another search? What use would it be, anyhow? If M’Innes perished, which we sincerely hpe he did not, the part could only find his bleaching bones – what earthly use would that do them? Now if they put a record in the archives of Menzies that in the year 3000 a.d., the mayor and councillors of the town are requested to institute a search for a certain man named M’Innes, who was believed to have been lost in the year 1896, they would possibly be doing future generations a certain amount of good, for the suppositionary bleaching bones by that time might have become interesting fossils, that is unless Menzies has fallen neck and crop into the background of oblivion, which does not seem at all unlikely as the world wags.

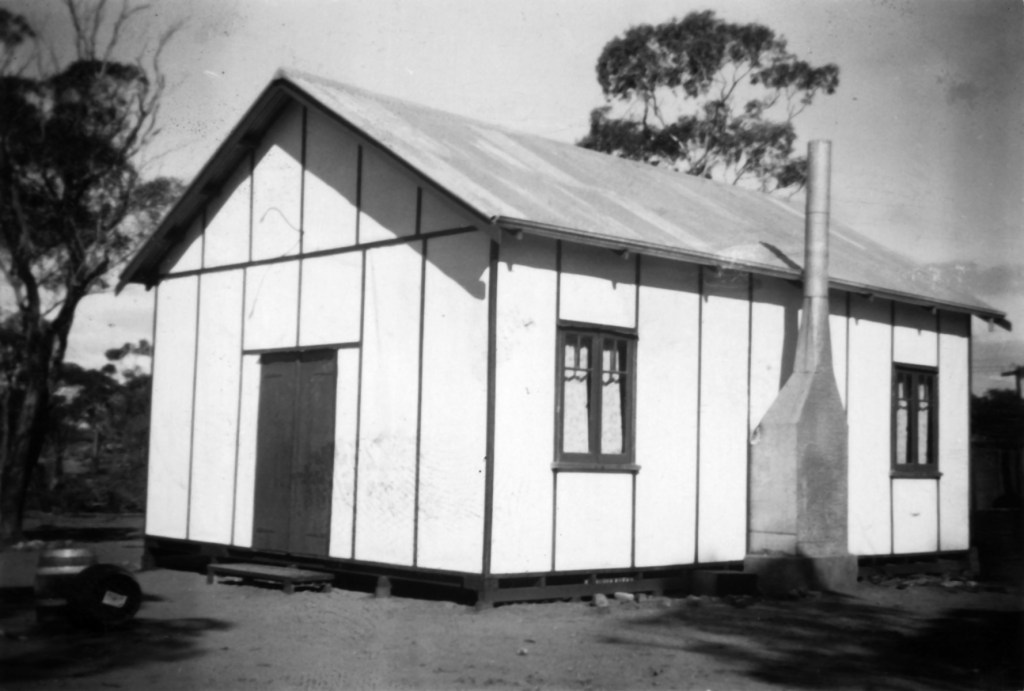

At the time of the disappearance, The North Coolgardie Herald and Menzies Times reported that Constable Sampson of Bardoc and a black tracker were searching unsuccessfully for the publican John M’Innes2. Mr M’Innes had made the trek through trackless and waterless country successfully on a number of previous occasions, but no trace was found of him after he left for Donkey Rocks in late December.

- “THE WEEKLY WHIRL.” Sunday Chronicle (Perth, WA : 1897 – 1899) 12 December 1897: 3. Web. 17 Feb 2024 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article257697205>. ↩︎

- “LOST IN THE BUSH.” The North Coolgardie Herald and Menzies Times (WA : 1896 – 1898) 30 December 1896: 2. Web. 17 Feb 2024 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article259770978>. ↩︎