The following is a detailed report of a cricket match that took place on this day in 1897 at Cossack between the Cossack and Roebourne teams. It was published in Northern Public Opinion and Mining and Pastoral News on Saturday, 19 June 1897.1

CATCHES.

By “SHORT SLIP.”

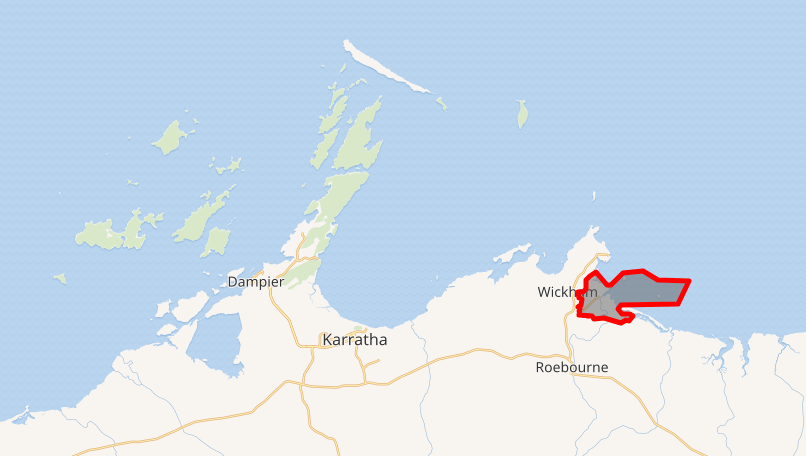

The Boebourne Rovers “trammed” to Cossack on Saturday. The first association match played at the port this season took place.

The game was well contested, and good feeling made for a close and exciting finish. A good number watched the game, but the fair sex had only one representative present. ‘Tis true for the poet when he describes the petticoat sporting fraternity as a “sit-me-on-the-bicycle sort of push.”

The Rovers proved the victors by eleven runs.

“Watty,” the Cossack barracker, was all there in his usual bass voice and sung himself hoarse. “Snap-shot” Renold, with his camera, took a “shot” at both teams, and “never smiled again.” He should have thrown the “X-rays” on them.

Like the “Arizona Kicker,” good old “Sol.” blessed the players with a beautiful day, and the Cossackites prepared a good wicket for the Boebourne boys.

Through the instrumentality of a few members of the home team, led by indefatigable “Donny,” a shed was erected on the ground, and the scorers were accommodated with a “cose” and a few “ax.l.” boxes to squat down on.

The Union Jack—or perhaps the Cossack coat-of-arms-out-of-pocket—was flying on top of the shed, whilst the decorations at the bottom comprised two fine jars of water (not of Babel, but of Nature).

There is no denying the fact that the pitch at Cossack, and also the fielding ground, is far superior to that of Boebourne, and if it always remained in the condition it was on Saturday, all matches could be played on the marsh.

The Rovers played a really well-combined game and deserved to win, whilst the Cossack lads defended splendidly and did everything in their power to avert defeat.

“Luck was agin’ them,” said Watty, after a whiskey and soda.

Whilst travelling with the cricketers on Saturday (not a Parliamentary team), our worthy and much-respected member, Mr. H. W. Sholl, M.L.A., opened his many-a-time generous heart and proved to those who travelled by the tram that he was a sportsman as well as a “Member of Parliament,” and a gentleman as well as a public “sarvint.” He informed the members of the B.C.C. that he was that day presenting a bat to the individual, of either team, who made the highest score in the match, for the sake of evincing some interest among the batsmen.

This goes to show that Mr. Sholl’s heart and soul were with them in their recreation, and he deserves the thanks of all true and honest sportsmen in both Boebourne and Cossack.

I may state that the genial skipper of the Rovers, “Sam” Hemingway, won the bat to which I refer, his score being 81, made by sterling cricket. I offer him my heartiest congratulations.

One of the most pleasing sights that I have yet seen on a North-West cricket ground appeared before me on Saturday. It was simply the Cossack “willow wielders” turning out in their true colours—wearing scalp-caps of yellow and black hue, and with a green kerchief (ould Oirish, begorra) round their waists.

It reminded me of an old English cricketer (Dr. Grace), who, when in Australia, had, on entering the Melbourne ground, decked himself with blue dungaree pants, and what he termed an “old physician’s waistband” (green). When the spectators eyed him, they shouted out, “We bar the Irish navvy!” But the good old medico held his peace, and the crowd silenced down.

The query is asked—”Why don’t the Boebourne teams play in their colours?” Echo answers—”They have none!”

At two o’clock, both captains met, and the coin was tossed, turning in favour of George Snook, who elected to bat. “Sam” Hemingway then led his men into the field, and at twenty minutes past two, a start was made.

“Uncle” Harding and “Bob” Selway were the first men to pad up and take strike for Cossack, while “Jim” Hubbard and “Jack” Keogh took the cudgels for the Rovers.

“Bob” did not celebrate a record reign at the crease. Taking strike to Hubbard, he received the dreaded “duck,” which he has for so long been unaccustomed to. This was rather unlucky for Cossack, to lose their best man by the first bell of the day, and there was “weeping and gnashing of teeth” when Bob returned to the shed.

“It was a splendidly pitched ball, and broke to the off, beating me all the way.” – Selway

“Donny” took the vacancy and, after making a dozen, was clean bowled by “Tommy” Molster, who was brought in from long-field to do the trundling. “Uncle” soon followed, being caught and bowled by “Sam” Hemingway. He had made nine by good cricket.

“Georgy” Fry and “Georgy” Brown, the two pavilion cricketers, made four and eight respectively. They were off duty (cricket, I mean) and did not take much advantage of their “staff.”

“Snoofie,” the skipper, played a free bat and made some very pretty strokes, notching fourteen before he drove one very hard to Jack Keogh, who accepted it. It was a splendid catch, and Jack received an ovation.

“Jum” Louden fell a victim to Tommy Molster, after breaking the shell of the “duck.”

“Watty” Moore surprised everyone by his fine exhibition, his leg hits being marvellous, and he received a cheer when he had carried out his bat for thirteen.

“Slurry” Wilson and “Carbine” Moore both succumbed to Hubbard before they had scored and joined the ranks of “Short-slip’s” spoon competition.

An amusing thing occurred while “Carbine” was batting. He played the first ball of Hubbard’s onto his cranium, and with a cricketer’s oath, the next one gave him a clip in the ear, but the third one hit the—w-i-c-k-e-t.

“Herb.” Birch, who was put in last wicket down (who should have followed the seventh man), just reached double figures when he was snapped up by Jim Hubbard.

Tommy Molster, in the long field, made a “bolster,” fell down, and got stuck in a mud-hole. Here’s to him, with “Short-slip’s” sympathy!

The ball went off the cricket bat,

And travelled far away!

“Tom” Molster in his big white hat

Fell on it in the clay.The clay was soft, the ball was round,

Poor “Tom” he couldn’t stir,

So all the boys they stood around

And left him in despair.He with the ball at last did rise

With language that was wicked,

And told them that he’d cause surprise

When he got at the wicket.Covered with mud, he took the ball

And bowled a maiden over,

And in the next surprised them all

By scattering bails in clover.

For fielding, Church, Naish, and Hemingway were excellent, and it speaks well for Cossack’s wicket-keeper that a bye was not recorded in the innings.

The bowling honours for the Rovers were carried off by Jim Hubbard, who came out of the cupboard (his shell, I mean), and got the splendid average of 5 wickets for 11 runs. A word of praise is also due to Tommy Molster, his 2 wickets only costing him 7 runs.

After a blow, the Rovers commenced their innings, having to make 72 to win. “Bannerman” Raymond and “Sam” Hemingway were the first representatives, and the bowlers were Brown and Louden.

“Banner,” after his usual careful play, had the misfortune to snick one of Louden’s into the hands of Brown and retired with four to his credit.

The skipper played a very useful innings. It was really a treat to watch his well-timed strokes and neat cuts, and when he had reached 81, he was captured by Selway. “Sam” was received with three times three when he reached the shed.

“Jim” Hubbard, after making seven, was foolishly run out. “Bert” Naish trebled his misfortune on Saturday, falling a victim to Brown for a duck.

“Herb.” Church, who had received a nasty blow on the left cheek through coming into contact with the ball, played a good innings and was bowled by Fry for a well-made 18.

“Jack” Keogh fell a victim to Fry for five, and “Burly” bowed to the same bowler for a unit. “Dawesie,” who must be credited with making the winning hit, cried ‘nough to Fry for 11. A.E.D. hit a fiver, which was the biggest hit of the day.

“Willie” Fuller threw his bat at Donny (unintentionally), and after making a single was bowled by Walter Moore. “Jack” Wotherspoon “spooned” the ball into the “dukes” of Fry.

Pass along the banjo!

“Oh Jack, why did you hit that ball?”

Cried Boebourne Rovers one and all.

“I went to place it to the leg,”

Said poor old “Wother,” with his egg.

The game was o’er, the match was won—

So it didn’t matter what he done.

But on this man there was a doom,

Because his name was Wotherspoon.

“Tom” Molster carried his bat to the wicket, but had no chance to use it.

George Fry did the trundling for the home team, bagging 6 wickets for 22 runs. Selway and Walter Moore also bowled well. Little “Donny” was the best man in the field, ably assisted by Brown and Harding, while “Snookie” performed well behind the sticks.

Owing to the bogey condition of the Cossack cricket ground, caused by the high tide at the port, the Civil Service–Cossack match has been postponed till today week.

Some of our local cricketers, I learn, are striving to arrange an all-day match (one end of the town against the other), for Wednesday next. It is to be hoped that “both ends will meet.”

“Short-slip” was met by an indignant cricketer the other day, and was thus warned:

“Look here you blonky (hic) quill-driver, if you (hic) say a word about me in the (hic) paper, I’ll punch your blinky nose (hic)… take it from me.”

I don’t think he was—d-r-u-n-k.

Source

- CATCHES. (1897, June 19). Northern Public Opinion and Mining and Pastoral News (Roebourne, WA : 1894 – 1902), p. 3. Retrieved June 11, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article255736548 ↩︎

- State Library of Western Australia, 2025. Cossack and Roebourne Cricket Teams. Photograph taken 1900 in the North West Australian series. Retrieved June 11, 2025 from

North West Australia ; BA338/1/36 ↩︎