The Unsung Pioneer of the Yilgarn: The Story of Richard Greaves

The history of Western Australia is inextricably linked to the glitter of gold. While names like Bayley and Ford often dominate the narrative of the great 1890s rushes, the foundations of these discoveries were laid years earlier by men whose names are less frequently celebrated. One such figure was Richard Greaves, a Victorian miner whose grit and keen eye for geology helped unlock the Yilgarn goldfield, paving the way for the legendary wealth of Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie.

The Early Spark of Discovery

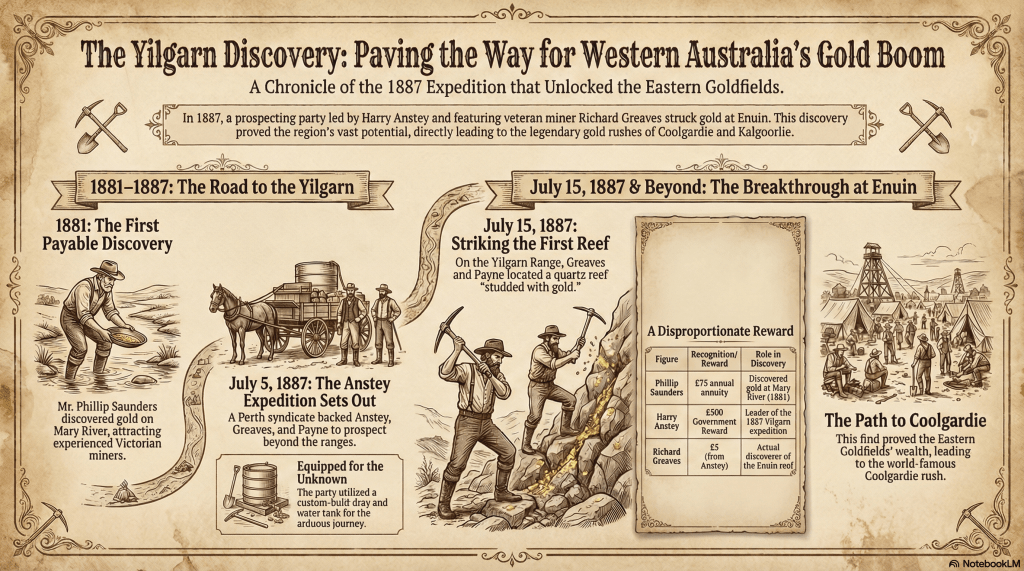

Before the Yilgarn was even on the map, Western Australia’s golden potential was largely a series of rumors and small-scale finds. The first “payable” quantity of gold was discovered in 1881 by Phillip Saunders on the Mary River in Kimberley. Though the Kimberley field was never a massive producer, it proved that the state held more than just traces of gold, acting as a magnet for experienced prospectors from the eastern colonies.

Among these arrivals was Richard Greaves. He landed in Western Australia in 1885 at the age of 35, bringing with him a lifetime of experience gained by following his father through the famous Victorian gold rushes. For a time, he worked as a plasterer in Perth, but the call of the “outback” was too strong to ignore.

The Lawrence Syndicate and the Trek East

In 1887, Greaves’ life took a pivotal turn when he met William Lawrence, a Perth boatbuilder who had seen promising gold specimens from the north. Lawrence, sensing an opportunity, formed a high-profile syndicate to fund an expedition. This group included several prominent Perth citizens, such as Dr. Scott (the Mayor of Perth) and future Premier George Leake.

The expedition was led by Harry Anstey, a metallurgist. Greaves and his partner, Edward Payne, were the hands-on prospectors. The terms were modest: thirty shillings a week, food, and a one-eighth share of any find. On July 5, 1887, the party set out from St. George’s Terrace in Perth, equipped with a specialized dray and a water tank, heading toward the unknown beyond the Toodyay ranges.

July 15, 1887: A Fateful Discovery

The journey was not easy. The party met other prospectors, like a man named Colreavy, who were so discouraged they urged Anstey’s team to turn back. However, Greaves and Payne pushed forward to Enuin, then part of George Lukin’s station.

The breakthrough occurred on the slopes of the Yilgarn Range. Greaves later recounted the moment they found a “floater” (a piece of ore detached from the main reef). As he and Payne worked the outcrop, they realized the magnitude of their find:

- The First Speck: Payne spotted a visible speck of gold in a sample.

- The “Half-Solid” Gold: Greaves turned over another piece of rock with his pick, discovering it was nearly half solid gold.

- The Reef: Within ten minutes, they located the main reef, finding quartz heavily studded with the precious metal.

This was the first payable gold ever found in the Eastern Goldfields.

Controversy and the “Cordelia” Mine

While the find was historic, it was also the source of long-standing bitterness. The Western Australian Government paid a £500 reward for the discovery, but it went to Harry Anstey as the leader of the party. Greaves later claimed he was the actual discoverer, but his official claim for recognition was rejected by the Mines Department on the grounds that he was a “paid servant” of the syndicate.

Greaves’ luck with official recognition didn’t improve. After the Enuin find, he and Payne discovered another rich outcrop about 12 miles away, which Greaves named the Cordelia mine. To mark the site, he dragged a log over the reef and set it on fire, leaving a heap of ashes as a marker.

For “old time’s sake,” Greaves shared the location of the Cordelia with Colreavy, the man he had met earlier on the trail. Shortly after, Colreavy announced a discovery at a place he called Golden Valley, which Greaves insisted was his Cordelia mine. Colreavy received a government reward; Greaves did not.

The Path to Coolgardie

Perhaps the most poignant part of Greaves’ story is how close he came to discovering Coolgardie. While at Enuin, an Aboriginal woman named Maggie told him of a place called “Coolgoon,” where she claimed there was “plenty of similar stuff”.

Greaves intended to investigate, but his health failed him. After multiple operations and being forced to wear a “leather waistcoat” for support, he attempted to return to the field but was too weak to continue. He was forced to turn back just as Bayley and Ford—who were eventually guided by native locals—made the find that would “stagger the world”.

Legacy of a Prospector

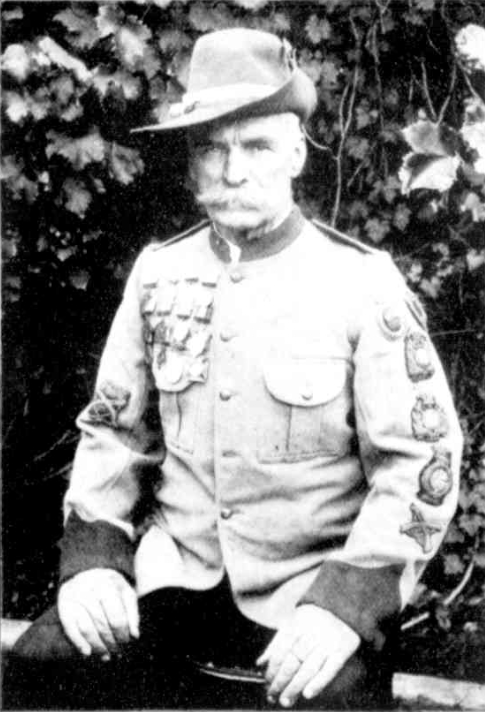

Richard Greaves never achieved the immense wealth that his discoveries generated for the state. He eventually found a quieter life as the caretaker of the James-street school and gained a reputation as a champion rifle-shot.

He died in 1916, but his 1903 book detailing his experiences ensures that his role in the Yilgarn—and his hand in the first reef found in the Eastern Goldfields—remains a matter of historical record. For history enthusiasts and casual readers alike, Greaves represents the thousands of “forgotten” miners whose persistence built the foundations of modern Western Australia.

Editor’s Note: This story was taken from an article that appeared in The West Australian on 2 July, 1936.1 If it interests you, then I recommend that you read the story in full on Trove.

- (1936, July 2). The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), p. 14. Retrieved January 27, 2026, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page3691361 ↩︎