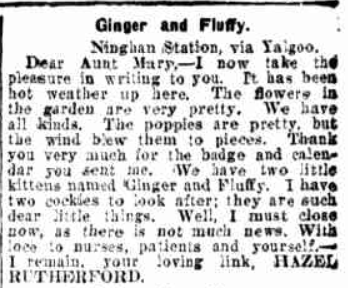

Searching for the ghost town/area Ninghan (occasionally spelled Ningan) I found a story which indicates the everyday dangers always present in outback Western Australia. When she was 11 years old, Hazel Rutherford, of Ninghan Station via Yalgoo wrote in to ‘Aunt Mary’ (children’s letters to the Silver Chain) about where she lived. She told of the spring near their homestead, the garden of poppy flowers, and her kitten. Hazel had five brothers and a sister. She also had a friend, Iris Vickery, and they went for long walks together. Ninghan Station still exists, and the descriptions of it are as picturesque now as they were in 1925.

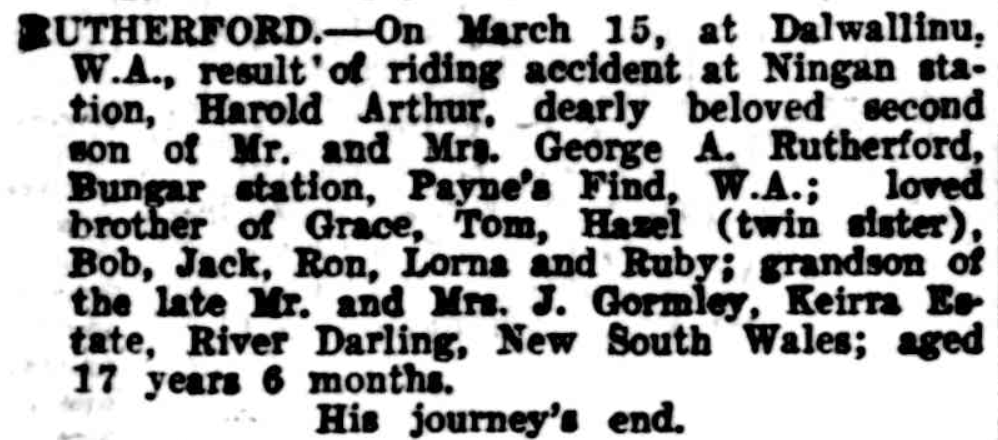

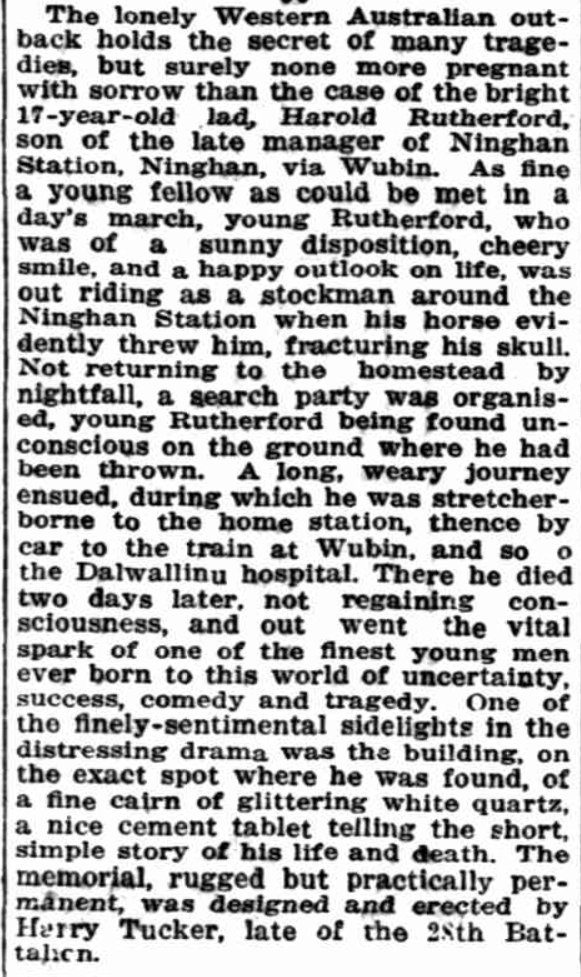

A few years later, Hazel’s name was again in the newspaper, but this time the information was not so benign. She was listed as family mourning the death of her twin brother, Harold Arthur Rutherford, who had died riding home from his day’s work as a stockman – he was 17 and six months. Harold was laid to rest where he was found, at Ninghan Station, which at the time was owned by Tom Elder Barr Smith. By that time, the Rutherford family seem to have moved to Bungar Station, Paynes Find which is still in the area. This I could not find. Perhaps the name has changed, or the land is divided now.

A postscript to this story was a request for compensation for Harold’s death, put forward by his father, George Arthur Rutherford, to Tom Elder Barr Smith, heir to a fortune in pastoral properties and owner of Ninghan Station. £75 was awarded under the Workers Compensation Act, on the grounds that Harold had partially supported his father and the family by some of his wages at the time he died. Iris Vickery, a bookkeeper to Mr Barr Smith, corroborated the information.

The Dalwallinu Register of Burials notes the grave, and also that the ashes of a relative, George Edward Rutherford, who died in 1990, were also interred there4.

Sources

- Ginger and Fluffy. (1926, January 21). Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 – 1954), p. 29. Retrieved August 20, 2024, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article37644656 ↩︎

- Family Notices (1932, April 14). The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), p. 1. Retrieved August 20, 2024, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32643172 ↩︎

- Peeps at People (1932, April 10). Sunday Times (Perth, WA : 1902 – 1954), p. 7 (First Section). Retrieved August 20, 2024, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article58661172 ↩︎

- Shire of Dalwallinu Burial Register ↩︎