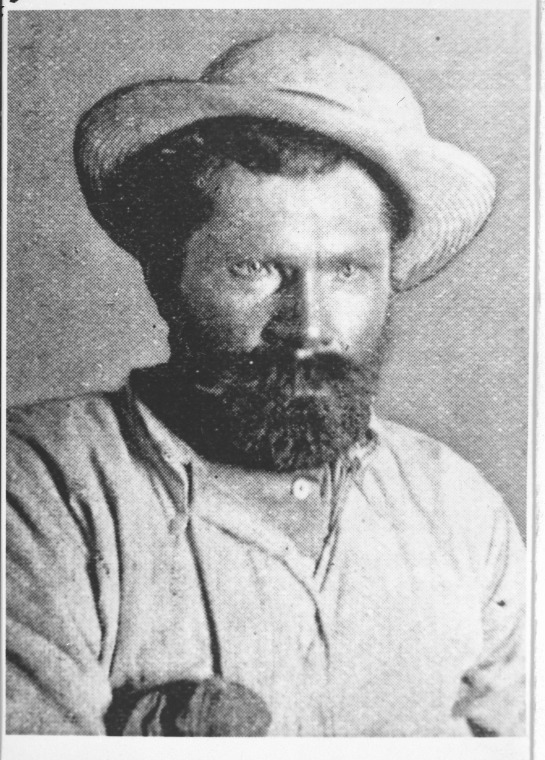

Author: Colin Judkins (Colin’s Facebook Profile), 11 January 2026

His name was “Russian Jack” although his real name was Ivan Fredericks, but that wouldn’t do in the Aussie outback, would it!!

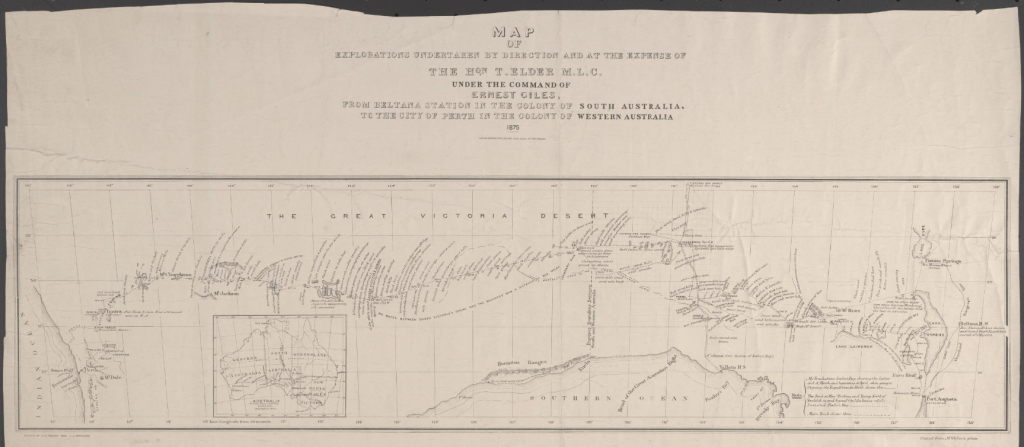

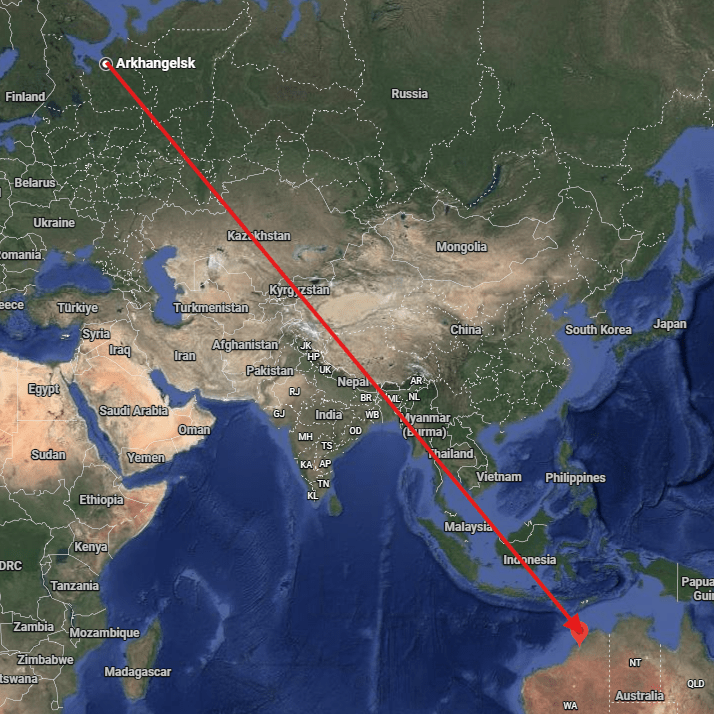

He came from the mostly frozen city of Arkhangelisk (located on the north coast of Russia), not far from Siberia. In the early 1880s he decided to head for Derby in the far North West of Western Australia. You could hardly find two locations more different and further from one another in the whole world.

Those who knew him described him as “a magnificent specimen of a man” he was said to be just under 7 feet tall and weighing a lean 18 stone in weight. He was believed to be “the strongest man in Australia” at that time.

He loved his food, consuming enormous amounts in a single sitting. Three pounds (1.5kg) of steak, a dozen eggs, a loaf of bread and a pound of butter (and that was just his entree!!). He supposedly liked emu eggs. “There was a lot more eating in them” he would often say.

In the small town of Derby, Jack constructed an abnormally large wheelbarrow, with shafts/handles over 2 metres long. A specially carved wooden (wide) wheel made it easier to negotiate both soft soils and the rough country of the outback, areas where he went searching for gold.

The long low wheelbarrow with straight shafts resembled a sled and it would most likely have been easier to pull than to push. With the friction on the wooden wheel, the average man had difficulty in moving the barrow at all, even when empty! Russian Jack would often push loads well in excess of 80 kilograms, and at times loads far greater than that!! (as you will see).

bored through the centre, around a foot thick.

When he and a mate were halfway to the Kimberley country, his companion fell ill. Jack loaded his mate’s swag and stores, on top of his already laden wheelbarrow, allowing the sick man to walk alongside.

Having travelled over 60 kms, his friend became too sick to walk any further, so Jack put him on top of the load and wheeled him along the track, sadly not long after that his mate died. He buried him beside the track and continued his journey alone.

During one of his early overland trips, Jack came across two elderly prospectors who were too exhausted to carry their swags and gear any further, they were resting in the shade of a tree waiting for death to end their suffering. He loaded their gear on to his wheelbarrow and helped them get to the nearest settlement some 50 ks further on.

On another occasion Jack saved another stricken gold prospector, (all of this rescuing must have been a real pain for him, but due to his kind nature, he just couldn’t leave anyone in need).

This man was called Halliday, he was found lying semi-conscious beside a lonely track in the Kimberley near Fitzroy Crossing, a victim of typhoid fever. Jack helped the sick man on to his wheelbarrow and pushed him and their combined camping gear across a few hundred kms of rugged country to the tiny township of Halls Creek. (Old Halls Creek, not where Halls Creek is today), there the sick man was given medical treatment and lived to tell the tale.

Duncan Road, Ord River

Lat/Long: -18.24854484895759, 127.78225683864191

One other recorded event was when Jack and a mate were returning from an unsuccessful prospecting venture inland when their food supply ran really low. His mate decided to chase a Roo on foot, tripped and broke his leg. In typical fashion Jack lifted his injured mate onto his wheelbarrow and pushed him to safety.

When they arrived in town, one of the locals mentioned that Jack must have travelled over a particular rough track, one that had heaps of pot holes and gullies along it. Jack told the admiring on-lookers, “I pushed him over a hundred miles (160 kms) in that damn wheelbarrow.” his mate with the broken leg, still sitting on it remarked drily, “Yes, and I’ll swear he hadn’t missed a rock or hole on the whole track.”

Jack was one of the first arrivals on the Murchison goldfields and at Cue, (roughly 700 ks north of Perth. The police “station” was just two tents and a rough enclosure for their horses. It was decided to get a large tree stump or log from some distance away, and transport it back to Cue on a wagon.

The log was set up near the police tents, they then fastened a strong chain to it and that became the Cue Gaol.

Jack was prospecting in the area when he came into town for supplies on one occasion. Prior to returning to his camp about 12 ks out of town, he decided to stop at the pub for a beer or three!! His enormous wheelbarrow was loaded with all his groceries, a bag of potatoes, drilling gear and a wooden box full of explosives. On top of that was casually placed a tin of 50 firing caps (extremely sensitive objects) particularly dangerous sitting on top of sticks of dynamite!!!

With the slightest jolt the firing caps could easily have caused a major explosion. Jack didn’t mind for when he left in the early evening he was happily drunk. He effortlessly took up the shafts of his great wheelbarrow and headed off, but being a bit under the weather (so to speak) he weaved all over the track trying to push it in the right direction towards his camp.

A policeman saw that he’d had a “few” so decided to help him get safely out of town. He then spotted the firing caps sitting precariously on top of the load. For his and everyone else’s safety the policeman wanted to detain him so he could sober up a bit.

He was unsure how to do it for Jack being so big and strong, he had to be handled cautiously at the best of times. His continued staggering all over the road whilst loudly singing a song in his raucous, booming voice had the “Copper” a tad nervous!! As they drew near the police tents he got his police mates to help stop Jack, they suggested quietly and diplomatically that he should re-pack his barrow.

By this time Jack was thirsty again so agreed to sit down quietly for a spell. As Jack rested, he dozed off and fell asleep. The police re-packed his barrow properly then handcuffed him to the huge log, wanting to restrain him until he had sobered up, he could then (hopefully) make his own way back to his camp in the bush the next morning.

Overnight the policemen were urgently called out of town to a disturbance. Somehow they completely forgot about Jack being chained to the large log near the police tents. Later the next day the policeman who had detained him suddenly remembered that he had left Jack secured to the log back at Cue.

Riding quickly back to town the policeman was stunned to find that Jack was gone, AND SO WAS THE LOG!! It would have taken four men to lift it so he reasoned that some of the residents had moved the log and Jack to a shady spot out of the sun.

The policeman conducted a quick search for him finding him quietly sitting at the bar of the open air pub. He was having a beer and a chat with the owner, the log was beside Jack, who was still chained to it!!

Apparently Jack woke up during the night with a terrible thirst, he could see a water bag hanging near one of the police tents and called out for a drink. There was no response so heaved the great log up on to his shoulder and walked to the tent. He then emptied the water bag and went back to sleep.

When he woke, the hot sun was beating down on him. “Dying” for a drink and not particularly fussed how he got it, he again heaved the huge tree stump off the ground, balanced it on his shoulder and headed off to the nearest pub a half a mile away.(far out, big time)!!

When it opened there was Jack, chained to the log asking for a cool ale to prevent him from dying of thirst. That’s where the policeman later found him saying “I thought I left you in goal, Jack”. “So you did,” he replied, “but it was a low act of you to leave me all night with no drink. Have a drink with me now and I’ll go back to goal.” With the amazed police officer in tow, Jack again shouldered the goal log and strolled back to the police tents where he restored the makeshift “goal” to its original position.

The officer then removed Jack’s chain and put a billy on a campfire and shared a cuppa, The policeman said to him: “You had better go back to your show (goldmine) now but next time you want to have a few drinks, don’t buy explosives at the same time” Later Jack thanked the police for preventing him leaving town with his firing caps unsecured.

He was asked what he would most like to achieve in his life. His reply was, “I would like to retire near a city and grow lots of vegetables, then sit down by myself and eat the lot”

Following Russian Jack’s death in 1904 at the age of 40, (apparently from pneumonia) an obituary in a Fremantle newspaper said: “Russian Jack, if there are Angels in Heaven who record the good deeds done on earth, thou wouldst have sufficient to thy credit to wipe out the many faults that common flesh is heir to.” How nice was that !!.

His death certificate records his profession as “market gardener,” revealing that the big man seemingly fulfilled his life-long ambition to have his own private vegetable supply.

Jack was buried in a paupers grave as he had no next of kin and very little wealth. Around 2015 money was raised and a suitable headstone was placed over his grave, to honour one of West Australia’s and indeed Australia’s most colourful characters and pioneers.

Today 122 years on from his death, Russian Jack’s loyalty to his fellow workers, mates4 and even people he didn’t know is still remembered and has become legendary in Australian folklore.

I hoped you enjoyed reading about one of the most remarkable characters to ever live and walk our fair land.

R.I.P. “Russian Jack”, you were a bloody ripper.5

Footnotes

- State Library of Western Australia, n.d. George Spences Compton collection of photographs of the Eastern Goldfields; 5001B/59. ↩︎

- Outside Halls Creek shire offices in the far north-west of Western Australia, this memorial to Russian Jack can be found. It commemorates his feats of carrying those needing assistance on his wheelbarrow. The sculpture cost over $20,000 (a fair bit of dough back when it was unveiled in 1979, it is not to scale as it would have been far too expensive to do so!! ↩︎

- Today the Cue Caravan Park houses the old gaol built in 1896. It was a temporary home to prisoners being transported from outback lock ups in the north until its official closed in 1914. It was however, still used as a lock up until the 1930s. (Shire of Cue) ↩︎

- One of the those events was the time that he pushed his sick mate over 300 kilometres in his wheelbarrow to Hall’s Creek. In reality it is thought to be closer to 60 ks that he pushed him, (Not sure that lessens the legend of the great man, still a Herculean effort I reckon!!). ↩︎

- Peter Bridge has recently published a book called “Russian Jack” it has a wealth of researched information on Ivan Fredericks. It points out that some of the stories and myths about him may have been exaggerated by those telling his story many years ago, (having a little bit of Mao added!). ↩︎