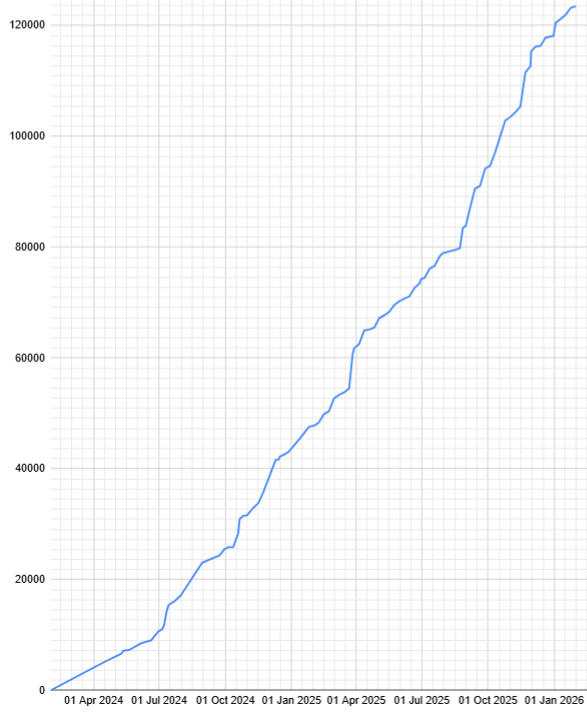

The total number of records captured as at 31 January 2026 was 123,471. Now that the very typical slow down over the festive season is past we will be seeing the also very typical ramp up in number of records collected. Congratulations to the project team who are working so hard to make this project great!!

Since the end of November, we have added about 40 new communities to the list of captured records – ranging (alphabetically) from Barrow Island to Yule River, and spread geographically all over our state.

As you can see from the list below, some of the record numbers are very low. This happens when we are researching one community and come across records for another community that is on our list. We capture the strays as we go along because we don’t want to miss anything!!

Once our website and search engine is fully operational you will be able to access some of these records. Here are the latest figures followed by a simple line graph showing the growth in total numbers:

List of Communities

Quick Tip: to quickly see if your favourite ghost town is already in this list, press CTRL+f [find].

| Community name (including some alternate names) | No of records collected |

|---|---|

| 25 Mile | 4 |

| 36 Mile Police Station | 52 |

| 4 Mile (Menzies) | 2 |

| 45 Mile | 3 |

| 71 Mile Well | 2 |

| 90 Mile | 319 |

| Abbott’s | 58 |

| Agnew | 4 |

| Aldersyde | 4 |

| Aldinga | 53 |

| Anaconda | 2 |

| Argyle | 1 |

| Argyle Police Station | 6 |

| Arrino | 2 |

| Austin | 3 |

| Baandee | 120 |

| Balkuling | 50 |

| Bamboo Creek | 38 |

| Bandee | 76 |

| Bardoc | 47 |

| Barrow Island | 1 |

| Barton | 88 |

| Beela Railway Siding | 1 |

| Benjaberring | 13 |

| Beria | 1 |

| Bernier Island | 2 |

| Big Bell | 6527 |

| Bila Railway Siding | 1 |

| Black Flag | 44 |

| Black Range | 14 |

| Bodallin | 6 |

| Bonnie Vale | 181 |

| Boogardie | 1 |

| Boorabbin | 4 |

| Bootenal | 237 |

| Bowgada | 1 |

| Boyadine | 172 |

| Boyerine | 400 |

| Broad Arrow | 58 |

| Brown Hill | 173 |

| Brown’s Mill | 23 |

| Buchanan River | 5 |

| Buldania | 196 |

| Bullabulling | 27 |

| Bullaring | 108 |

| Bullfinch | 66 |

| Bulong | 1038 |

| Bummers Creek | 57 |

| Bungarun Lazarette | 60 |

| Bunjil | 25 |

| Buntine | 213 |

| Burakin | 8 |

| Burbanks | 2 |

| Burbidge | 3 |

| Burnakura | 57 |

| Burtville | 42 |

| Butcher’s Inlet | 16 |

| Butterfly | 1 |

| Calooli | 30 |

| Camden Harbour | 14 |

| Camden Harbour Expedition | 8 |

| Cane Grass Swamp Hotel | 11 |

| Canegrass | 102 |

| Carbine | 512 |

| Carinyah | 38 |

| Caron | 11 |

| Cashmans Bore | 1 |

| Celebration City | 5 |

| Chesterfield | 1 |

| Comet Vale | 70 |

| Condon | 3 |

| Coodardy | 6 |

| Coonana | 91 |

| Cork Tree Flat | 10 |

| Corunna Downs Station | 17 |

| Cossack | 42260 |

| Craiggiemore | 9 |

| Cuddingwarra | 17 |

| Cue | 6006 |

| Culham | 180 |

| Darlot | 5 |

| Dattening | 3 |

| David Copperfield Mine | 13 |

| Davyhurst | 25 |

| Day Dawn | 3459 |

| Delambre Island | 2 |

| Derdebin | 37 |

| Derdibin | 1 |

| Dinningup | 2 |

| Dinninup | 1538 |

| Diorite King | 8 |

| Dore Island | 2 |

| Dowerin Lakes | 405 |

| Dudawa | 15 |

| Duketon | 12 |

| Dundas | 1 |

| Dunnsville | 1 |

| East Kirup | 126 |

| East Kirup Timber Mill | 8 |

| East Kirupp | 65 |

| Edjudina | 40 |

| Ejanding | 9 |

| Elverdton | 2 |

| Eradu | 758 |

| Erlistoun | 27 |

| Eticup | 7 |

| Eucalyptus | 157 |

| Eucla | 159 |

| Euro | 30 |

| Ferguson Mill | 104 |

| Ferguson Timber Mill (Lowden) | 1 |

| Ferguson Timber Mill (Yarloop) | 2 |

| Fernbrook | 18 |

| Feysville | 350 |

| Field’s Find | 215 |

| Fields Find | 650 |

| Fletcher’s Creek | 4 |

| Fly Flat | 5 |

| Gabanintha | 902 |

| Galena | 181 |

| Galena Bridge | 3 |

| Gap Well | 3 |

| Garden Gully | 9 |

| Garden Well | 2 |

| Geraldine | 141 |

| Geraldine Mine | 293 |

| Ghooli | 343 |

| Gindalbie | 1 |

| Golden Valley | 14 |

| Goodwood | 29 |

| Goodwood Timber Mill (Donnybrook) | 888 |

| Goomarin | 1373 |

| Goongarrie | 6409 |

| Gordon | 5 |

| Grants Patch | 1 |

| Grass Patch | 15 |

| Greenough River | 513 |

| Grimwade | 1 |

| Gum Creek | 8 |

| Gunyidi | 22 |

| Gwalia | 4689 |

| Haig (Railway Siding) | 3 |

| Hampton Plains | 7 |

| Harris | 6 |

| Hawk’s Nest | 53 |

| Hawkes Nest | 6 |

| Hawkes Nest Gold Mine | 4 |

| Hawks Nest (Laverton) | 9 |

| Hearson Cove | 1 |

| Higginsville | 700 |

| Holden’s Find | 2 |

| Holyoake | 10 |

| Howatharra | 2 |

| Ida H | 1 |

| Ives Find | 1 |

| Jarman Island | 40 |

| Jibberding | 729 |

| Jindong | 14 |

| Jitarning | 133 |

| Jonesville | 1 |

| Kallaroo | 64 |

| Kamballie | 130 |

| Kanowna | 12973 |

| Kathleen | 8 |

| Kathleen Valley | 29 |

| Kintore | 16 |

| Kodj Kodjin | 46 |

| Kokeby | 2 |

| Kookynie | 2232 |

| Korrelocking | 16 |

| Kudardup | 27 |

| Kukerin | 1 |

| Kulja | 24 |

| Kunanalling | 166 |

| Kurnalpi | 60 |

| Kurrajong | 8 |

| Kwelkan | 26 |

| Lake Austin | 178 |

| Lake Darlot | 15 |

| Lancefield | 8 |

| Lawlers | 20 |

| Lennox | 3 |

| Linden | 2 |

| Londonderry | 103 |

| Ludlow | 4 |

| Ludlow (Capel / Busselton) | 462 |

| Ludlow Bridge | 1 |

| Lunenberg | 80 |

| Lunenburgh | 11 |

| Malcolm | 767 |

| Mallina | 10 |

| Mangowine | 33 |

| Marchagee | 8 |

| Mark’s Siding | 10 |

| Marrinup | 4 |

| Maya | 44 |

| Merilup | 13 |

| Mertondale | 5 |

| Mia Moon | 320 |

| Mia-Moon | 350 |

| Miamoon | 1853 |

| Minnivale | 219 |

| Mogumber | 1557 |

| Mollerin | 3 |

| Moolyella | 1 |

| Moore River Native Settlement | 455 |

| Mornington Timber Mills (Wokalup) | 1 |

| Mount Erin | 59 |

| Mount Erin Estate | 3 |

| Mount Ida | 2 |

| Mount Jackson | 16 |

| Mount Kokeby | 140 |

| Mount Malcolm | 327 |

| Mount Margaret | 137 |

| Mount Monger | 5 |

| Mount Morgans | 36 |

| Mt Erin | 119 |

| Mt Ida | 1 |

| Mulga Queen Community | 190 |

| Mulgabbie | 8 |

| Mulgarrie | 2 |

| Mulline | 1 |

| Mulwarrie | 2 |

| Mundaring Weir | 277 |

| Murrin Murrin | 531 |

| Nalkain | 818 |

| Nalkain Railway Siding | 12 |

| Nannine | 282 |

| Nanson | 134 |

| Naretha Railway Siding | 9 |

| Needilup | 2 |

| Neta Vale Telegraph Station | 16 |

| New England | 1 |

| Newlands | 97 |

| Newlands Timber Mill | 9 |

| Niagara | 294 |

| Niagara (North) | 5 |

| Ninety Mile | 139 |

| Ninghan | 2 |

| Ninghan Station | 15 |

| Nippering | 6 |

| No 6 Pump Station (Ghouli) | 44 |

| Noman’s Lake | 414 |

| Nomans Lake | 91 |

| North Baandee | 1 |

| North Bandee | 40 |

| Nugadong | 889 |

| Nullagine | 17 |

| Nungarin (North) | 27 |

| Nyamup | 5 |

| Ogilvie | 53 |

| Ogilvies | 10 |

| Old Dowerin | 143 |

| Old Halls Creek | 3782 |

| Onslow (Old) | 27 |

| Ora Banda | 326 |

| Paddington | 7 |

| Payne’s Find | 136 |

| Paynesville | 23 |

| Peak Hill | 18 |

| Piesseville | 51 |

| Pilbarra | 33 |

| Pindalup | 19 |

| Pindalup Ports No.1 Timber Mill (Dwellingup) | 20 |

| Pindalup Railway Siding | 20 |

| Pingarning | 97 |

| Pingin | 48 |

| Pinjin | 159 |

| Pinyalling | 1 |

| Plavins | 15 |

| Port George IV | 1 |

| Quindalup Timber Mills | 3 |

| Red Lake School | 8 |

| Redcastle | 12 |

| Reedy | 14 |

| Roaring Gimlet | 149 |

| Rothesay | 42 |

| Rothsay | 65 |

| Sandstone | 22 |

| Shannon | 19 |

| Shay Gap | 1 |

| Sherlock | 3 |

| Siberia | 12 |

| Sir Samuel | 2 |

| Smithfield | 9 |

| Spargoville | 1 |

| Speakman’s Find | 1 |

| St Ives | 1 |

| Stake Well | 2 |

| Star Of The East | 22 |

| Stratherne | 13 |

| Sunday Island | 48 |

| Sunday Island Misson Station | 44 |

| Surprise | 71 |

| Surprise South | 5 |

| Tampa | 9 |

| Tardun | 1 |

| Taylor’s Well | 316 |

| Taylors Well | 22 |

| Tenindewa | 8 |

| The Island Lake Austin | 3 |

| Tien Tsin | 62 |

| Trafalgar | 346 |

| Tuckanarra | 106 |

| Tullis | 16 |

| Two Boys | 13 |

| Ularring | 327 |

| Ullaring | 25 |

| Vivien | 33 |

| Vosperton | 1 |

| Waddi Forest | 3 |

| Wagerup | 2 |

| Walgoolan | 34 |

| Wannamal | 1 |

| Warriedar | 16 |

| Webb’s Patch | 1 |

| Whim Creek | 2 |

| White Feather | 813 |

| White Hope | 1 |

| White Well | 9 |

| Wilga | 3 |

| Wittenoom | 1 |

| Woodley’s Find | 4 |

| Woolgangie | 3 |

| Woolgar | 318 |

| Woop Woop Timber Mill | 305 |

| Wyening | 30 |

| Wyola | 744 |

| Xantippe | 22 |

| Yaloginda | 10 |

| Yandanooka | 148 |

| Yankee Town | 29 |

| Yarri | 1 |

| Yerilla | 49 |

| Yetna | 58 |

| Yornup | 73 |

| Youanmi | 18 |

| Youndegin | 5 |

| Yuba | 25 |

| Yule River | 6 |

| Yundamindera | 1 |

| Yunndaga | 324 |

| Zanthus | 20 |

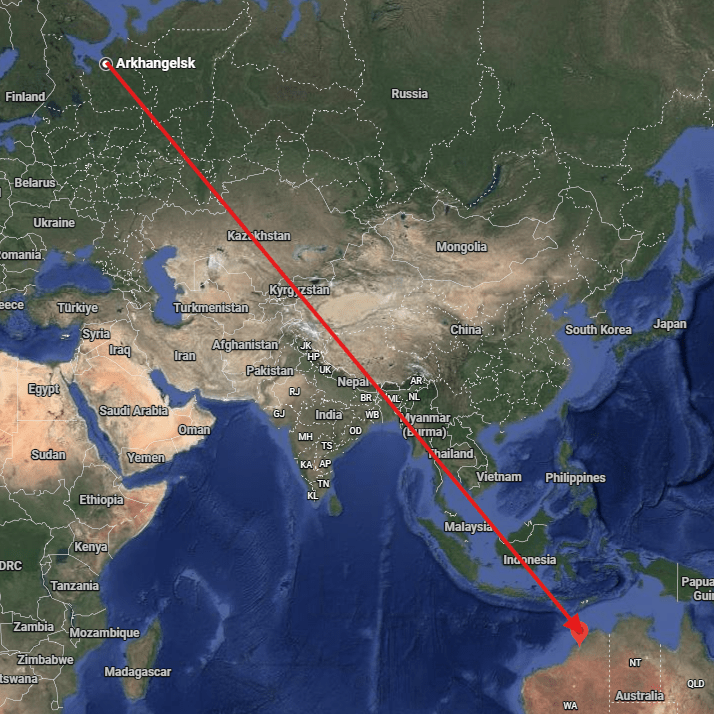

Progress Graph